“As human populations continue to expand farther out into natural areas,” warns The Wildlife Society in a February 17 blog post, “domesticated animals will continue to be at risk for exposure to diseases carried by their wild relatives.” Considering the domesticated animals in question are cats, the organization’s apparent concern is almost touching. Almost.

Actually, TWS is, not surprisingly, much more concerned about cats transferring disease from “their wild relatives” to humans. Results of a recent study, published a month ago in the online, open-access journal PLoS ONE, suggests TWS blogger “policyintern,” illustrate “the importance of keeping domesticated cats close to home to prevent disease transmission among cats and to humans.”

Among those diseases is one that’s been getting lots of attention recently in the mainstream media: toxoplasmosis.

And just how likely is it that your cat will give you toxoplasmosis?

Not very—at least according to this latest research. (The study also looked at bartonellosis and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus, but I’ll save those for another post.) To begin with, “feral, free ranging domestic cats were targeted in this study” [1, emphasis mine], not pets. And, despite what TWS and others would have us believe, contact with these cats is relatively uncommon.

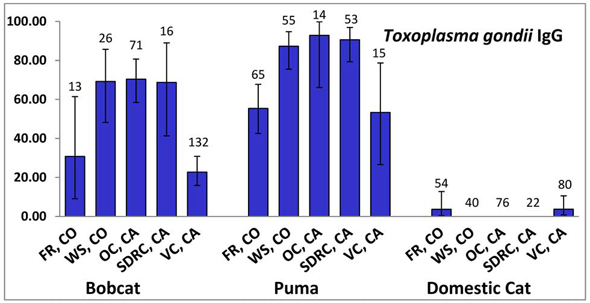

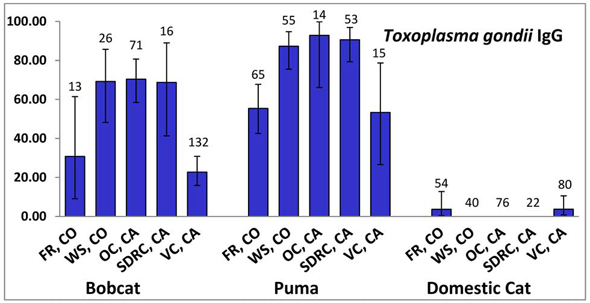

Then there’s the unexpectedly low infection rate reported by the authors of the study: just 1 percent for domestic cats, as compared to 75 percent for pumas and 43 percent for bobcats. Based on previous studies, one would expect seroprevalence rates of 62–80 percent for feral cats. [2] (Even “owned” cats* were found to have rates of 34–36 percent. Interestingly, the highest rate of seroprevalence was found among cats living on farms: 41.9–100 percent.)

Seroprevalence, with bars representing 95 percent confidence intervals, of T. gondii IgG,** for domestic cats, bobcats, and pumas at all study locations (FR = Front Range, CO; WS = Western Slope, CO; OC = Orange County, CA; SDRC = San Diego/Riverside Counties, CA; VC = Ventura County, CA). Sample sizes are listed above columns.

This should be big news for TWS.

At the very least, the low infection rates found in feral cats—combined with the much higher rates in bobcats and pumas—raise serious questions about domestic cats’ role in environmental contamination of T. gondii. Just a year ago, an article published in a special section of The Wildlife Professional called “The Impact of Free Ranging Cats,” was unambiguous: “the science points to [domestic] cats.” [3]

“Based on proximity and sheer numbers, outdoor pet and feral domestic cats may be the most important source of T. gondii oocysts in near-shore marine waters. Mountain lions and bobcats rarely dwell near the ocean or in areas of high human population density, where sea otter infections are more common.” [3]

And, over the past several months, TWS Executive Director/CEO Michael Hutchins has used the TWS blog to hammer the point home, arguing (and twisting the facts along the way), for example, that a 2011 NIH study provided “further evidence that feral cats are a menace to our native wildlife and should be controlled.”

In July, it was the grave threat to humans:

“T. gondii infection has recently been correlated with the incidence of Parkinson’s disease, autism, and schizophrenia in humans, and it has long been known to cause fetal deformities and spontaneous abortions in pregnant women… Let’s hope that public health officials, including the CDC, begin to take note of these growing concerns about cats and their implications for human health.”

In fact, this latest study suggests that such concerns may not be growing at all, at least where toxoplasmosis is concerned. On the other hand, the simpler, scarier story—cats as a menace to both wildlife and humans—is certainly an easier sell for TWS.

* I assume this refers to indoor/outdoor cats, but have not chased down the individual studies to confirm this.

** Refers to immunoglobulin, or antibody, G (IgG), “which is detectable for ≥52 weeks after infection,” as compared to immunoglobulin M (IgM), “which indicates recent infections and is usually detectable ≤16 weeks after initial exposure.” [1]

Literature Cited

1. Bevins, S.N., et al., “Three Pathogens in Sympatric Populations of Pumas, Bobcats, and Domestic Cats: Implications for Infectious Disease Transmission.” PLoS ONE. 2012. 7(2): p. e31403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0031403

2. Dubey, J.P. and Jones, J.L., “Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and animals in the United States.” International Journal for Parasitology. 2008. 38(11): p. 1257–1278. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4S85DPK-1/2/2a1f9e590e7c7ec35d1072e06b2fa99d

3. Jessup, D.A. and Miller, M.A., “The Trickle-Down Effect.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 62–64.