Given the junk science, red herrings, and desperate scaremongering that plague Cat Wars, why is Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology rolling out the red carpet for co-author Peter Marra? Read more

“Hawaii’s Crazy War” is a shameful, inexcusable rehash of the same tired framing we’ve been seeing for at least 20 years now.

Read more ›Cat Wars is, to anybody familiar with the topic, an obviously desperate attempt to fuel the ongoing witch-hunt against outdoor cats “by any means necessary,” including the endorsement of discredited junk science, an oceanful of red herrings, and B-movie-style scaremongering. The book’s central thesis—that outdoor cats must be eradicated in the name of biodiversity and public health—is, like the authors’ credibility, undermined to the point of collapse by weak—often contradictory—evidence, and a reckless arrogance that will be hard to ignore even for their fellow fring-ervationsists.

In early 2010, Peter Marra co-authored a desperate appeal to the conservation community, calling for greater opposition to trap-neuter-return (TNR). “The issue of feral cats is not going away any time soon,” he and his colleagues warned, “and no matter what options are taken, it may well be a generation or more before we can expect broad-scale changes in human behavior regarding outdoor cats.” [1] Since then, Marra, who’s been with the Smithsonian Institution’s Conservation Biology Institute since 1999 and now runs its Migratory Bird Center, has only become more desperate. Read more

As most readers are undoubtedly aware, today is National Feral Cat Day. And at the risk of stating the obvious: NFCD has clearly become, to borrow a trendy phrase from social media, “a thing.” Now in its 14th year, there are hundreds of events going on around the country to mark the occasion.

All of which must be terribly frustrating for TNR-deniers. Thus, their increasingly desperate attempts to oppose, any way they can, TNR and community cat programs.

Witness, for example, Cats, Birds, and People: The Consequences of Outdoor Cats and the Need for Effective Management (PDF), a presentation by Grant Sizemore—who may or may not be the American Bird Conservancy’s Director of Invasive Species Programs. (As we’ll see shortly, it’s surprisingly complicated.)

It’s not clear exactly who these 33 slides are intended to help. After all, to anybody even remotely familiar with the issue, it’s immediately apparent that Sizemore’s claims—the “consequences” mentioned in the presentation’s title—are flimsy at best.

Equally apparent: Sizemore and ABC are not—though ABC’s been on this witch-hunt for 17 years now—about to provide any solutions.

Not only is the presentation available on ABC’s website, Sizemore’s now taking the show on the road. Last month, for example, he was in Ellenton, Florida, as part of a Coyotes and Feral Cats forum, hosted by the Suncoast Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area.

No doubt, most readers will miss such opportunities. Here, then, are 11 of the presentation’s “highlights”—my humble gift on National Feral Cat Day 2014. Read more

“I’m pretty sure both sides are going to hate it,” warned New York magazine writer Jessica Pressler, referring to her feature for this week’s issue, “Must Cats Die So Birds Can Live?” When I first spoke to Pressler in March, she’d indicated that she knew the subject was complex. Her most recent e-mail, however, sent just a few days before the story was published, made it clear that the piece had taken an unfortunate turn: “In the end there were so many different bits that needed to be covered,” Pressler explained. “A lot of it ended up being about the argument between the two sides.”

Still, hate is a strong word. How about enormously disappointed? Read more

It came as some surprise, a couple weeks ago, to learn that Stanley Temple was a guest on WHYY’s Radio Times, discussing the Smithsonian’s “killer cat study.” (Full disclosure: I’ve yet to listen to the episode.) Temple was, as I’m sure most readers know, the man behind the infamous Wisconsin Study (from which, not surprisingly, Scott Loss, Tom Will, and Peter Marra borrow for their own “estimate”), so his position on the issue is no surprise.

What surprised me (as I’ll explain below) was that he wanted to weigh in publicly.

And then, a week-and-a-half later, Temple was doing it again, with an opinion piece in Friday’s Orlando Sentinel (where, on that same day, Alley Cat Allies co-founder and president Becky Robinson, called the Smithsonian/USFWS paper “wildly speculative” in an op-ed of her own). Read more

The National Geographic Society is, according to its website, “one of the largest nonprofit scientific and educational institutions in the world.” I’m not going to dispute the relative size of the organization, but an article posted Tuesday on its News Watch blog raises doubts about their commitment to science and education.

The piece, which is billed as “an interview with Dr. Michael Hutchins,” is not much of an interview at all, but an easy platform for Hutchins, former executive director and CEO of The Wildlife Society, to vilify invasive species in general and—not surprisingly—free-roaming cats in particular. As I pointed out in my online comment (still awaiting moderation), one would expect some insightful follow-up questions on a topic that, as contributing editor Jordan Carlton Schaul acknowledges, “has generated contentious debate among a number of factions, including conservation scientists and activist communities.”

For starters: How would restrictions or outright bans on TNR, such as those proposed by Hutchins, benefit the wildlife he claims to want to protect? Read more

A recent study finds important differences between cat caretakers and bird conservationists when it comes to their attitudes and beliefs about the impacts of free-roaming cats and how to best manage them. In the end, however, the methods employed lead to far more questions than answers.

“Because western society’s orientations toward wildlife is becoming more moralistic and less utilitarian,” explain the authors of a study recently published online in PLoS ONE, “conservation biologists must develop innovative and collaborative ways to address the threats posed by feral cats rather than assuming wholesale removal of feral cats through euthanasia is a universally viable solution.” [1] Not surprisingly, the authors fail to acknowledge that “euthanasia” hasn’t proven to be a viable [see Note 1] solution anywhere but on small oceanic islands. Still, given the sort of recommendations typically generated by the conservation biology community on this subject, I suppose we have to recognize this as some kind of progress. Read more

Putting on any conference is a tremendous undertaking. But the challenges involved in pulling together The Outdoor Cat: Science and Policy from a Global Perspective went far beyond the logistics of wrangling 20-some speakers and 150 or so attendees. For starters, there was deciding who should (and should not) be invited to present. (More on that shortly.) And then there’s the fact that, no matter what happens, you’re bound to be criticized.

There’s simply no way to get something like this completely right, no matter who’s in charge or how much planning goes into it.

And so, I give a lot of credit to the people involved—who knew all of this, and did it anyhow. Those I know of (and I’m sure to be leaving out many others, for which I apologize) include John Hadidian, Andrew Rowan, Nancy Peterson, Katie Lisnik, and Carol England from the Humane Society of the United States; and Aimee Gilbreath and Estelle Weber of FoundAnimals. Many of you told me, very modestly, that this conference was “a start.”

Fair enough, but it’s a very important one. Five or 10 years from now, we might look back and call it a milestone.

Here, then, are some snapshots of the various presentations (in the order in which the they were given). Read more

Coming up December 3rd and 4th: The Outdoor Cat: Science and Policy from a Global Perspective, a conference with an ambitious—and admirable—goal:

Coming up December 3rd and 4th: The Outdoor Cat: Science and Policy from a Global Perspective, a conference with an ambitious—and admirable—goal:

“To bring together scientists, technical experts, and others with an interest in the constellation of issues tied to the presence of free-roaming, abandoned, and outdoor cat populations in our world, and to take the measure of contemporary scholarship with the goal of forging a stronger union between knowledge, evidence, insight and policy.”

Although I won’t be presenting, I’ll be in attendance—with plenty of questions and comments, of course. And I’m encouraging anybody with an interest in the science and policy issues surrounding free-roaming cats to attend as well. It’s an excellent—and all too rare—opportunity to hear a broad range of perspectives, with speakers from the fields of conservation biology, wildlife rehabilitation, veterinary medicine, municipal animal services, animal law, and more.

I’ll be posting more about the conference in the near future, but wanted to get this out there so that anybody interested can make plans. Registration is just $135.

Many thanks to the Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy, FoundAnimals, and the Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association for making the conference possible!

“Bird lovers have just derailed a plan to save some alley cats from death at the hands of animal control,” writes Bruce Leshan in a WUSA-9 TV story that aired Tuesday. “When Prince George’s County Council woman Mary Lehman proposed to order animal control to release” TNR cats, “she ran into a storm of criticism at a council public hearing.” [1]

As Lehman pointed out, “This is not trail-blazing legislation. Fairfax County, Baltimore City, and Washington, DC, all have programs.”

So what’s the hold-up in Prince George’s County? Mostly the American Bird Conservancy, it seems.

“The American Bird Conservancy, which opposes ‘trap, neuter, and return,’ says what you are really doing is releasing predatory, ownerless cats back into the wild to kill again.” [1]

Presumably, ABC will be leading the charge when Lehman brings her bill up again in the fall, which she’s promised to do. Perhaps they can then explain to the Prince George’s County Council—and everybody else—the rationale for their position. Where’s the science to support the numerous claims they make to the media? Read more

“Cat Fight,” which appears in the latest issue of Conservation magazine, does little to cut through the rhetoric or clear up the numerous misrepresentations that plague the debate over free-roaming cats.

![]()

There is, it’s often said, no such thing as bad PR. Even so, I’m not thrilled with the way I’m portrayed in an article appearing in the current issue of Conservation. It’s only a couple of quotes, but still, I worry that I come off as more of a bomb-thrower than anything else.

“Wolf writes a blog, Vox Felina,” explains writer John Carey, in “Cat Fight,” “which regularly excoriates wildlife biologists for what Wolf calls their ‘sloppy pseudo-science.’ He charges that ‘the science in Dauphine’s paper about cats was so horrific that she should have never made it out of graduate school’ and that ‘Peter Marra is taking six bird deaths and predicting the Apocalypse.’”

As I told Carey via e-mail, just after the piece was published online, I don’t believe the quotes are accurate. Carey, on the other hand, assures me (in a cordial, professional manner typical of our exchanges) that “the quotes are exactly what [I] said.” (Neither of us recorded our conversation.)

“I know I realized immediately when you said those things that they were precisely the type of colorful statements that illustrate the nature of the debate, so I did appreciate you using such colorful language.”

Fair enough. Perhaps it’s not all the important if the content isn’t precisely correct—the tone is certainly accurate.

If I am a bomb-thrower, though, I am at least a well-informed bomb-thrower. And the “targets”—to extend the metaphor—have, simply put, got it coming to them. Carey acknowledges that I “do an excellent job scrutinizing the scientific evidence, and have clearly thought deeply about both sides of the issue.” Unfortunately, that doesn’t come across to Conservation readers.

That said, I want to make it clear: I’m grateful to have been included in the piece, and grateful, too, for my conversations with Carey. And whatever quibbles I have about my portrayal pale in comparison to various other aspects of “Cat Fight.”

Stuffing the Ballot Box

Referring to Peter Marra’s well-publicized catbird study, Carey writes: “Predators nabbed nearly half the birds, and cats were the number one predator.” [1]

Number one predator?

Certainly, this was the message Marra emphasized to the press—but I thought I’d straightened this out with Carey on the phone, and with a follow-up e-mail.

Here’s what Marra and his colleagues report in their paper:

A total of 69 fledglings were monitored, of which 42 (61 percent) died over the course of the study. Of those mortalities, 33 (79 percent) were due to predation of some kind. Eight of the 33 predatory events were observed directly: six involved domestic cats, one a black rat snake, and one a red-shouldered hawk.

That leaves 25 predation events (76 percent) for which direct attributions could not be made—which, in and of itself, raises serious questions about Carey’s “number one predator” claim.

About those other 25: Marra and his co-authors concede that “not all mortalities could be clearly assigned.” Seven were attributed to rats or chipmunks because they were “found cached underground,” while another one was attributed to birds because the remains were found in a tree.

In addition, 14 mortalities “could not be assigned to a specific predator.” Which leaves three: “fledglings found with body damage or missing heads were considered symptomatic of cat kills.” [2]

In fact, it’s rather well known that such predatory behavior is symptomatic not of cats, but of owls, grackles, jays, magpies, and even raccoons [3–5]—something I addressed in an October 2010 post (and discussed with Carey).

All of which is difficult to reconcile with Marra’s claim, in “Cat Fight,” that he and his colleagues “were very conservative assigning mortality to cats,” [1] and with his apparent confidence (shared by Carey) in putting cats at the top of the list.

Curious, too, that, although Carey opens his article with Nico Dauphine’s December 2011 sentencing hearing, he never mentions the fact that Marra was Dauphine’s advisor at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. (I suppose the connection isn’t something Marra brags about these days.)

The Cats Came Back

Carey argues that “moving cat colonies away from areas that harbor threatened species is a no-brainer” but points out that “it doesn’t always work.”

“In Fortescue, New Jersey, a colony of feral cats was moved away from the shore of Delaware Bay in 2011 to help protect red knots, which stop there in huge numbers to gorge on horseshoe-crab eggs to fuel their long migration from the tip of South America to the Arctic. But after only a few months, cats were back.” [1]

Here, I’ll defer to Animal Protection League of New Jersey attorney Michelle Lerner, whose comment was the first posted after “Cat Fight” was available online:

“The details about the Fortescue cats, with which I was involved, are incorrect. The colony was not ‘moved,’ it was removed completely. 40 cats were moved to a fence enclosure on a farm several counties away, 7 went to a sanctuary in another state, others went to barns or were friendly enough to be adopted. Removal was used, which is what the anti-TNR people always want. The only difference is the cats were not killed—something that was possible because of limited numbers. It is true that, due to the vacuum effect, different cats then showed up. The nonprofit doing the removal keeps trapping there in coordination with animal control to try to get them all. A few per month show up. But this is why TNR advocates warn removal never really works without intensive management and repeat trapping, and why statistical studies have shown it takes 10 times the effort to control a colony through removal as through TNR. Because there is a reason the cats were there in the first place and more will just move in—more who are unneutered—if the cats are removed.”

It’s worth pointing out, too, that, unlike the current relocation effort, taxpayers would be footing the bill for an ongoing lethal roundup.

And I wish Carey had included a bit of additional context here. The greatest threat to those red knots, from what I can tell (admittedly, doing nothing more than a quick Google search), has little to do with cats being fed nearby. According to The Wetlands Institute:

“…overharvesting of female horseshoe crabs by commercial fishermen, coupled with loss of spawning habitat resulting from beach erosion associated with sea level rise, has resulted in a precipitous decline in the Delaware Bay horseshoe crab population, and therefore the number of eggs available to feed migratory birds. This, in turn, has led to a dramatic decrease in the size of annual red knot migrating populations, to the point that red knots have been proposed for federally endangered status.”

Indeed, the Delaware Nature Society reports: “In 2008, New Jersey placed a moratorium on horseshoe crab harvests until the red knot numbers rebound.”

The Scientific Community v. The People of the District of Columbia

If Marra hasn’t come to Dauphine’s defense, Chris Lepczyk has—with the kind of confidence he (and Marra) usually reserve for vilifying free-roaming cats.

“‘I am 100 percent confident she was not poisoning cats,’ says University of Hawaii wildlife ecologist Christopher Lepczyk, who fears that she was convicted in part because of her articles about the cat-predation problem. ‘I don’t think anyone in the scientific community agrees that she is guilty.’” [1]

That’s quite an endorsement—especially in light of… you know, the facts.

On December 14th, the day Dauphine was sentenced, CNN reported that Superior Court Judge A. Truman Morrison III “said he had received a number of letters from people who know Dauphine.”

“He said such letters usually try to make a case that the verdict was in error, but in this case, the judge said, no one quarreled with the guilty verdict… Morrison said it was clear from letters written by Dauphine’s colleagues that ‘her career, if not over, it’s in grave jeopardy.’ The judge said that was already partial punishment for her actions.”

But Lepczyk’s right when he says the verdict was, in part, the result of Dauphine’s writings—just not in the way he suggests. Indeed, the day Dauphine was found guilty, The Washington Post reported: “Senior Judge Truman A. Morrison III said it was the video, along with Dauphine’s testimony, that led him to believe she had ‘motive and opportunity.’”

“He specifically pointed to her repeated denials of her writings. ‘Her inability and unwillingness to own up to her own professional writings as her own undermined her credibility,’ Morrison said.”

All of which—not to put too fine a point on it—was included in my numerous posts following the case. Perhaps Lepczyk ought to subscribe to Vox Felina.

I’ve been saying for nearly two years now that Dauphine’s professional work on the subject of free-roaming cats—cited and promoted with great enthusiasm before all this nasty press attention—is as indefensible as the actions that landed her in DC Superior Court. It’s a shame Carey didn’t pin down Lepczyk (and others) on that point.

Numb and Numb-er

If Carey included me in “Cat Fight” because of my colorful language, I have to imagine Stephen Vantassel, project coordinator of distance education for the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s School of Natural Resources, was included for his unintended irony.

Referring to the toll cats take on wildlife, Vantassel told Carey, “The numbers are mind-numbing.” [1]

Actually, “mind-numbing” is a fitting description for the content of, and motivation behind, Feral Cats and Their Management, the well-publicized paper Vantassel co-authored in late 2010. Not only do the authors fail to get a handle on the predation numbers, they reveal a significant lack of understanding of the key issues surrounding cats and predation in general. Indeed, they misread, misinterpret, and/or misrepresent nearly every bit of research they reference. And, some of what the authors include isn’t valid research to begin with.

Two years later, it seems he’s still got nothing to contribute to the discussion.

OK, maybe that’s being too harsh. Consider what Vantassel has to say, in the sidebar that accompanies “Cat Fight,” about the uncertainty surrounding the legal status of free-roaming cats: it “has essentially turned outdoor cats into protected predators.” [6]

Protected predators?

Now, here’s a subject Vantassel knows well. After all, his PhD (theology) dissertation was dedicated to: “…fur trappers who, every winter, brave the harsh weather in continuance of America’s oldest industry. Regrettably, they must also endure the ravages of urban sprawl and the derision of an ungrateful and ignorant public.” [7]

Wisconsin: Landmarks and Mirages

My greatest disappointment with “Cat Fight”—one shared by others I’ve spoken with—is Carey’s inclusion of the infamous “Wisconsin Study.”

“In a landmark study in Wisconsin, Stanley Temple, now professor emeritus of forest and wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin, and his colleagues radio-collared free-ranging rural cats, watched the animals’ hunting behavior, and examined their stomach contents. (An inflammatory and inaccurate press report that implied that the researchers had killed the cats for the stomach contents—in fact, they used an emetic—led to death threats against Temple.) The study showed that each cat killed an average of 5.6 birds a year. With an estimated 1.4 million free-ranging rural cats just in Wisconsin, that’s nearly 8 million birds.” [1]

When I spoke with Carey, he’d already talked to Temple. And when he referred to a predation study Temple had done, I stopped him in his tracks: If Temple conducted any such work, it was never published.

What has been published involved combining cat density numbers Temple and graduate student John Coleman had gathered by surveying “farmers and other rural residents in Wisconsin for information about their free-ranging (not house-bound) cats” [8] with predation numbers from studies conducted in the 1930s and 1950s. All of which is explained in a 1992 article the two wrote for Wildlife Control Technology:

“…our four year study of cat predation in Wisconsin, completed in1992, coupled with data from other studies, allows us to make a reasonable estimate of birds killed annually in this state… At the high end, are estimates from diet studies of rural cats that indicate at least one kill per cat per day, resulting in over 365 kills per cat per year [9–11]. Other studies report 28 kills per cat per year for urban cats, and 91 kills per cat per year for rural cats [12].” [13]

“Using low values,” then, Temple and Coleman multiplied their estimated 1.4 million rural free-roaming cats in the state by 28 (“twice urban kill rate”), and then multiply that by 20 percent (the “low dietary percent,” as they call it, though it’s actually a gross misinterpretation of Mike Fitzgerald’s work, as Ellen Perry Berkeley points out in her 2004 book TNR Past Present and Future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement [14]). The resulting “estimate” is “7.8 million birds killed annually.”

Twenty years later, though, the story seems to have changed dramatically.

Now, we’re to believe that Temple and Coleman’s study (funded, by the way, with “about $100,000 … from the [University of Wisconsin], U.S. Agriculture Department and the state Department of Natural Resources” [15]) revealed an average predation rate of 5.6 birds/year/cat. And that the 7.8 million figure comes not from “coupling” Temple and Coleman’s density work with others’ predation studies, but from their work alone.

Or perhaps the two methods resulted in exactly the same estimate.

Which, as I told Carey after reading the article, would be one hell of a coincidence. In fact, the very sources he cites call into question—if not discredit entirely—Temple’s claim.

Simply put: Carey failed to dig into this deeply enough. Instead of further perpetuating the myth of the Wisconsin Study, he might have exposed it for what it is: little more than a few misguided (and overpriced) back-of-the-envelope calculations—which Temple himself backed away from during a 1994 interview with The Sonoma County Independent: “They aren’t actual data; that was just our projection to show how bad it might be.” [16]

Or, failing that, then at least ignore the thing entirely.

Landmark study? Only insofar as it was instrumental in launching what’s become a witch-hunt against free-roaming cats in this country.

• • •

According to the magazine’s website, “Conservation stories capture the imagination and jump-start discussion.” Unfortunately, I don’t see “Cat Fight” adding much to the discussion—a missed opportunity in a debate where such opportunities are few and far between.

I agree with Carey that, as he notes in the article’s closing paragraph, “these great societal debates … are contested on a battleground of conflicting emotions, moral values, and ideologies. Facts alone rarely break up the fight.”

On the other hand, I don’t see how we’re going to break it up if we don’t first get the facts straight.

Literature Cited

1. Carey, J., “Cat Fight.” Conservation. 2012. March. http://www.conservationmagazine.org/2012/03/cat-fight/

2. Balogh, A., Ryder, T., and Marra, P., “Population demography of Gray Catbirds in the suburban matrix: sources, sinks and domestic cats.” Journal of Ornithology. 2011: p. 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0648-7

http://nationalzoo.si.edu/scbi/migratorybirds/science_article/pdfs/55.pdf

3. Thompson, B., The Backyard Bird Watcher’s Answer Guide. 2008: Bird Watcher’s Digest.

4. Bird, D.M., “Crouching Raptor, Hidden Danger.” The Backyard Birds Newsletter. 2010. No 5 (Fall/October).

5. Anderson, T.E., Identifying, evaluating and controlling wildlife damage, in Wildlife Management Techniques. 1969, Wildlife Society: Washington. p. 497–520.

6. Carey, J., “The Uncertain Legal Status of Cats.” Conservation. 2012. March. http://www.conservationmagazine.org/2012/03/legal-status-of-cats/

7. Vantassel, S.M., Dominion over Wildlife?: An Environmental Theology of Human-Wildlife Relations. 2009: Resource Publications.

8. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., “Rural Residents’ Free-Ranging Domestic Cats: A Survey.” Wildlife Society Bulletin. 1993. 21(4): p. 381–390. http://www.jstor.org/pss/3783408

9. Errington, P.L., “Notes on Food Habits of Southwestern Wisconsin House Cats.” Journal of Mammalogy. 1936. 17(1): p. 64–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1374554

10. Parmalee, P.W., “Food Habits of the Feral House Cat in East-Central Texas.” The Journal of Wildlife Management. 1953. 17(3): p. 375-376. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3797127

11. Eberhard, T., “Food Habits of Pennsylvania House Cats.” The Journal of Wildlife Management. 1954. 18(2): p. 284–286. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3797736

12. Mitchell, J.C. and Beck, R.A., “Free-Ranging Domestic Cat Predation on Native Vertebrates in Rural and Urban Virginia.” Virginia Journal of Science. 1992. 43(1B): p. 197–207. www.vacadsci.org/vjsArchives/v43/43-1B/43-197.pdf

13. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., “How Many Birds Do Cats Kill?” Wildlife Control Technology. 1995. July–August. p. 44. http://www.wctech.com/WCT/index99.htm

14. Berkeley, E.P., TNR Past present and future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement. 2004, Bethesda, MD: Alley Cat Allies.

15. Imrie, R. (1997). Professor Says Predatory Cats Are Taking Toll on Ecosystem. St. Paul Pioneer Press, p. 1B,

16. Elliott, J. (1994, March 3–16). The Accused. The Sonoma County Independent, pp. 1, 10,

I’ve been a big fan of FixNation since contacting them, nearly a year ago, to clear up bogus allegations made in the Toronto Star by documentary filmmaker Maureen Palmer, who’d visited the clinic while filming Cat Crazed. The response I received was prompt and professional. And, it turns out, the beginning of an ongoing conversation.

Last month, while on a business trip to Los Angeles, I had the pleasure—finally—of seeing the FixNation operation for myself, beginning with their bimonthly Catnippers clinic, an all-volunteer community outreach/spay-neuter program now in its 12th year. A few days later, I toured the facility under “normal” conditions—meaning two veterinarians and seven staff sterilizing and vaccinating (and addressing a host of other health issues) 80–90 cats each day (with an ease and efficiency that would put many manufacturing facilities to shame, to say nothing of our healthcare providers).

Since opening its doors in July 2007, FixNation has sterilized and vaccinated more than 60,000 cats (not including the 16,000 or so brought in through Catnippers), more than 85 percent of which were feral, stray, or abandoned—receiving services at no charge to their caretakers (owners of pet cats are charged a modest fee).

All of which would be impressive enough. But in L.A.—which has more or less become ground zero for the TNR debate since a January 2010 injunction put an end to City support of trap-neuter-return—what FixNation has accomplished is nothing short of heroic.

The Injunction

The original complaint—filed by the Urban Wildlands Group, Endangered Habitats League, Los Angeles Audubon Society, Palos Verdes/South Bay Audubon Society, Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society, and the American Bird Conservancy—was brought under the California Environmental Quality Act, with the plaintiffs arguing, for instance, that TNR “can cause significant adverse environmental impacts by causing proliferation of rats and raccoons and creating water pollution problems.”

(As for how the restriction—or elimination, as ABC has proposed—of TNR would benefit the wildlife these groups claim to protect is anybody’s guess, and a topic for another post.)

Under the provisions of the injunction (in its revised version, filed with the court in March 2010), the City, its Board of Animal Services Commissioners, and its Department of Animal Services are prohibited from “promoting TNR for feral cats and encouraging or assisting third parties to carry out a TNR program.”

City agencies are no longer allowed to:

Nevertheless, TNR continues in L.A.—with many supporters more determined than ever. And I understand the City of Los Angeles is working (albeit far too slowly) to get the injunction lifted. Still, the loss of City-funded vouchers—which provided a substantial portion of overall revenue for many TNR programs—is taking its toll. According to founders Mark Dodge and Karn Myers, FixNation lost about $300,000 in annual revenue, more than 20 percent of its yearly budget.

The fact that they’ve been able to continue their community outreach and provide no-/low-cost spay/neuter services for the past couple of years is, as I say, truly heroic. But now, as Myers explains in a video released late last week, FixNation needs our help.

Today, We Are All Angelenos

Charity, it’s often said, begins at home. And I do what I can to support local TNR and low-cost spay/neuter programs. But the stakes are extraordinarily high in L.A.—in terms of lives saved or lost, but also in terms of the city’s symbolic value as a community committed to trap-neuter-return despite both the injunction and the faltering economy. Which is why I also support the organizations doing the heavy lifting there—among them, FixNation.

If you’re able to make a (tax-deductible) donation, I encourage you to do so. If not, please pass the word along to other TNR supporters.

Need a little more incentive? For the rest of the month, PetSmart Charities will match every “new donor” dollar up to $51,000. You can even turn your holiday shopping into a contribution: FixNation will receive 5 percent of December sales from Moderncat Studio, makers of beautifully designed cat toys, scratchers, and more.

Thank you.

Literature Cited

1. Urban Wildlands Group et al. vs. City of Los Angeles et al. (Case No. BS 115483). Stipulated Order Modifying Injunction. March 10, 2010. Los Angeles Superior Court.

It’s always good to see the Humane Society of the United States supporting and promoting TNR. After all, it wasn’t all that long ago when HSUS was on the other side of the issue. In 1997, when the American Bird Conservancy launched its Cats Indoors! campaign, the organization was “singled out as its ‘principal partner in this endeavor.’” [1]

On Monday, President and CEO Wayne Pacelle, waded into the feral cat/wildlife debate on his blog (brought to my attention by a helpful reader), noting that HSUS “work[s] for the protection of both feral cats and wildlife.”

HSUS is, says Pacelle, “working to find innovative, effective, and lasting solutions to this conflict.” In Hawaii, for example (“an ideal environment for free-roaming cats and a global hotspot for threatened and endangered wildlife”) HSUS is “meeting with local humane societies, state and federal wildlife officials, non-governmental organizations, and university staff to find solutions to humanely manage outdoor cat populations and ensure the protection of Hawaii’s unique wildlife.” (HSUS may want to add Hawaii’s various Invasive Species Committees to that list. If recent efforts are any indication, they’re contributing to the environment impact.)

I can certainly understand HSUS’s current focus on Hawaii, and I look forward to seeing the results of their efforts. It’s not difficult to imagine such results being adopted more broadly. (Tackle the really tough job first, and the others will be easy by comparison, right?)

Still, it’s important to remember that TNR opponents aren’t limiting their attention to such hotspots.

Beyond Hawaii

The Wildlife Society, for example, in its position statement (issued in August) on Feral and Free-Ranging Domestic Cats (PDF), calls for “the humane elimination of feral cat populations,” as well as “the passage and enforcement of local and state ordinances prohibiting the feeding of feral cats.”

Earlier this month, TWS hosted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s workshop, Influencing Local Scale Feral Cat Trap-Neuter-Release Decisions, at its annual conference.

And in October, ABC sent a letter to mayors of the 50 largest cities in the country “urg[ing them] to oppose Trap-Neuter-Re-abandon (TNR) programs and the outdoor feeding of cats as a feral cat management option.” (This, ABC claims, will “stop spread of feral cats.” I e-mailed Darin Schroeder, ABC’s Vice President for Conservation Advocacy, asking that he explain the biology and/or logic behind this miracle cure, but he never replied.)

Common Ground(?)

But we’re all after the same thing, right—no more “homeless” cats? The key difference being how we approach the problem?

I used to think so. Now, I’m not so sure.

TWS, ABC, and other TNR opponents are calling for the extermination—on the order of tens of millions—of this country’s most popular pet. Without, it must be recognized, a plan of any kind, or, given our decades of experience with lethal control methods, any hope of success. Nevertheless, they persist—grossly misrepresenting the impacts of cats on wildlife and public health in order to drum up support.

Common ground has proven remarkably elusive, and collaboration risky.

In the Spring issue of The Wildlife Professional (published by TWS) Nico Dauphine portrayed the New Jersey Audubon Society as sellouts for participating in the New Jersey Feral Cat & Wildlife Coalition (which included several supporters of TNR, including HSUS), a collaborative effort funded by the Regina R. Frankenberg and Geraldine R. Dodge foundations. [2, 3] The group’s commendable work, culminating in a pilot program based on their “ordinance and protocols for the management of feral cat colonies in wildlife-sensitive areas in Burlington County, New Jersey,” [4] (available here) has, from what I can tell, received little attention.

All of which suggests that we’re actually talking not only about very different means, but also very different ends.

• • •

How does one find common ground in the midst of a witch-hunt?

Earlier this month, Alley Cat Allies co-founder and president Becky Robinson proposed a crucial first step: “stop pitting species against species.”

“Today, I call on the leaders of the American Bird Conservancy, The Wildlife Society, and the leadership of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who persist in using flawed science and vicious rhetoric like Dauphine’s to blame cats for species decline, to stop.”

After which, there’s plenty of “real work” (some of which may, ironically, prove rather straightforward and uncontroversial) to be done, of course. Still, perhaps the situation in Hawaii is urgent enough, and the stakes high enough, to focus the mind—to get us that far.

Literature Cited

1. Berkeley, E.P., TNR Past present and future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement. 2004, Bethesda, MD: Alley Cat Allies.

2. Dauphine, N., “Follow the Money: The Economics of TNR Advocacy.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 54.

3. Stiles, E., NJAS Works with Coalition to Reduce Bird Mortality from Outdoor Cats. 2008, New Jersey Audubon Society. http://www.njaudubon.org/Portals/10/Conservation/PDF/ConsReportSpring08.pdf

4. n.a., Pilot Program: Ordinance & Protocols for the Management of Feral Cat Colonies in Wildlife-Sensitive Areas in Burlington County, New Jersey. 2007, New Jersey Feral Cat & Wildlife Coalition. p. 17. http://www.neighborhoodcats.org/uploads/File/Resources/Ordinances/NJ%20FeralCat&Wildlife%20Ordinance&Protocols_Pilot_7_07.doc

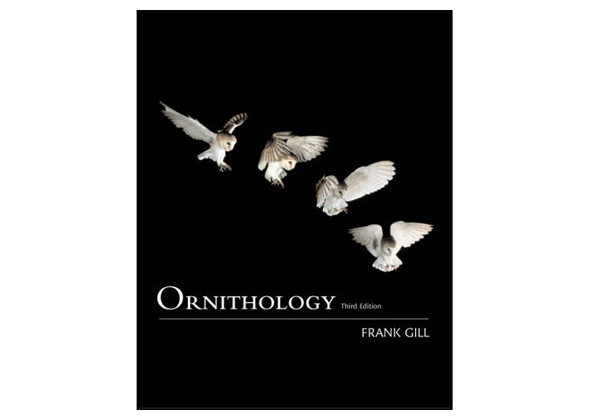

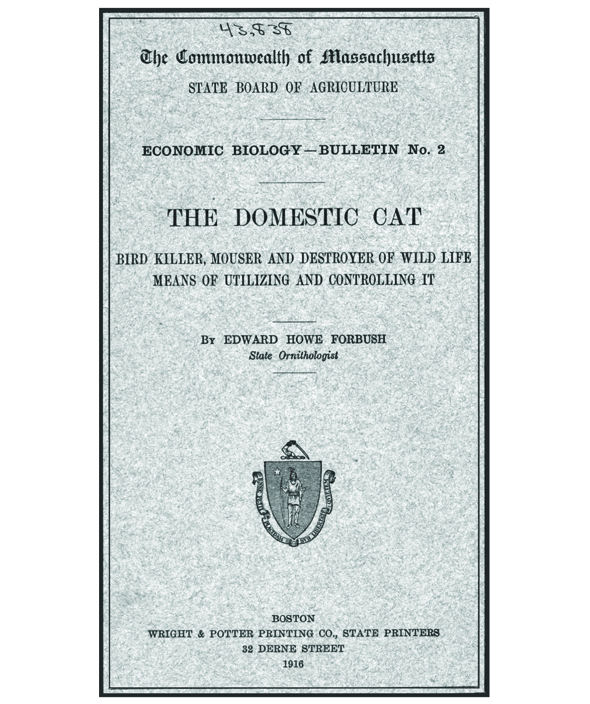

For more than 20 years now, Gill’s classic text has been required reading for ornithology students. While the book’s attention to conservation issues has expanded over its three editions, its treatment of the impact of cats on bird populations reflects an unsettling shift away from science.

The hoards of students descending upon college campuses this fall will—despite the rise of the eco-friendly PDF and a great variety of online content—more often than not find their arms and backpacks stuffed with old-school printed-and-bound books. Among them will be Frank Gill’s Ornithology, a regular offering on campus bookstore shelves for 21 years now.

Gill’s Ornithology is, I’m told by one Vox Felina reader, “considered (at least in these parts) the text regarding ornithology.” From what I can tell, it’s popularity as required reading for third- and fourth-year undergraduates isn’t limited to any one region of the country. Indeed, according to Amazon.com, the book is “the classic text for the undergraduate ornithology course.” Its third edition, published in 2007, “maintains the scope and expertise that made the book so popular while incorporating a tremendous amount of new research.”

Unfortunately, none of this new research made it into the section—a single paragraph—meant to address the “threat” of cats. Indeed, students interested in this topic are better off with the first edition, published 17 years earlier.

First Edition

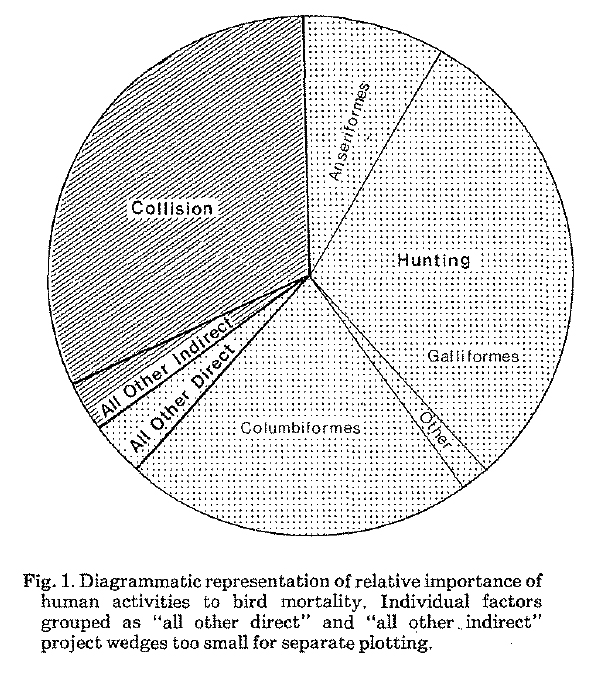

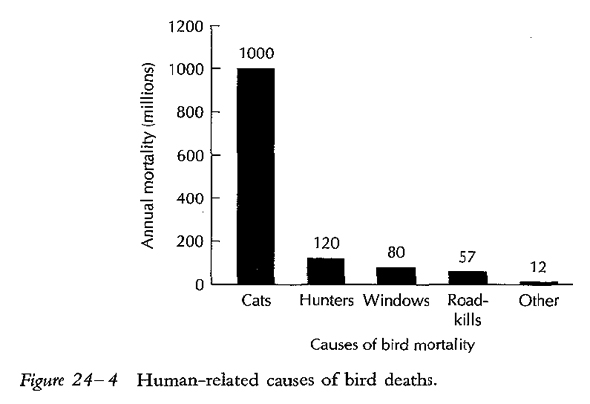

“The numbers of deaths attributable directly or indirectly to human actions each year during the 1970s are staggering,” writes Gill in the 1990 edition of Ornithology, “but are apparently minor in relation to the population level.” [1] Citing a 1979 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report by Richard C. Banks, Gill continues:

“Human activities are responsible for roughly 270 million bird deaths every year in the continental United States. This seemingly huge number is less than two percent of the 10 to 20 billion birds that inhabit the continental United States and appears to have no serious effect on the viability of any of the populations themselves, unlike human destruction of breeding habitat and interference with reproduction… Miscellaneous accidents such as impact with golf balls, electrocution by transmission lines, and cat predation, may amount to 3.5 million deaths a year.” [1]

Predation by cats (included under “All Other Indirect”), then, according to Banks, represents about 1.3 percent of overall human-caused mortality—a loss of, at most, 0.04 percent of the U.S. bird population annually. By contrast, hunting and “collision with man-made objects” combine to make up “about 90 percent of the avian mortality documented” in Banks’ report. [2]

Second Edition

Five years later, in the second edition, the story changes dramatically. Gill discards Banks’ reference to cats and uses his 270 million figure purely for dramatic effect—the set-up for a punch line in the form of Rich Stallcup’s back-of-the-envelope guesswork (which Stallcup himself considered “probably a low estimate” [3]). Gill even includes a bar chart to drive the point home. (Apparently, he didn’t find Banks’ pie chart compelling enough to include in the his first edition of Ornithology.)

“Human activities are directly responsible for roughly 270 million bird deaths every year in the continental United States, about 2 percent of the 10 to 20 billion birds that inhabit the continental United States (Banks 1979)… Dwarfing these losses are those attributable to predation by pets. Domesticated cats in North America may kill 4 million songbirds every day, or perhaps over a billion birds each year (Stallcup 1991). Millions of hungrier, feral (wild) cats add to this toll, which is not included in the estimate of 270 million bird deaths each year.” [4]

But Stallcup’s “estimate”—published in the Observer, a publication of the Point Reyes Bird Observatory (which Stallcup co-founded)—lacks even the slightest scientific justification. In fact, “A Reversible Catastrophe” is little more than Stallcup’s advice—at once both folksy and sinister—about defending one’s garden from neighborhood cats (“…try a B-B or pellet gun. There is no need to kill or shoot toward the head, but a good sting on the rump seems memorable for most felines, and they seldom return for a third experience.” [3]).

“Let’s do a quick calculation, starting with numbers of pet cats. Population estimates of domestic house cats in the contiguous United States vary somewhat, but most agree the figure is between 50 and 60 million. On 3 March 1990, the San Francisco Chronicle gave the number as 57.9 million, ‘up 19 percent since 1984.’ For this assessment, let’s use 55 million.

“Some of these (maybe 10 percent) never go outside, and maybe another 10 percent are too old or too slow to catch anything. That leaves 44 million domestic cats hunting in gardens, marshes, fields, thickets, empty lots, and forests.

“It is impossible to know how many of those actively hunting animals catch how many birds, but the numbers are high. To be very conservative, say that only one in ten of those cats kills only one bird a day. This would yield a daily toll of 4.4 million songbirds!! Shocking, but true—and probably a low estimate (e.g., many cats get multiple birds a day).” [3]

It’s hardly surprising that Stallcup’s “estimate” grossly exaggerates predation rates since his research never went any further than the Chronicle’s mention of the U.S. pet cat population. His assumptions about how many of these cats go outdoors and their success as hunters stand in stark contrast to the trend suggested by pet owner survey results and various predation studies (some of which suggest that just 36–56 percent of cats are hunters. [5, 6])

(It was, no doubt, the “shocking” aspect of Stallcup’s numbers that appealed to Nico Dauphine, who, in her “Apocalypse Meow” presentation, acknowledges that Stallcup “didn’t do a study” but nevertheless concludes, inexplicably, that his “is a conservative estimate.”)

Unnatural Selection

So, how did Stallcup’s indefensible “estimate” make it into the standard ornithology textbook? It was, Gill told me recently by e-mail, “one of the few refs [he] could find.”

Referring to what he calls “the great cat debates,” Gill writes: “I claim no great expertise or authority… now or in the ancient histories of early textbook editions.”

Fair enough. Writing, editing, and revising multiple editions of Ornithology was an enormous undertaking—one for which Gill deserves much credit. But there was, available at the time, work by scientists who, unlike Stallcup actually studied predation. Indeed, even before the first edition of Ornithology was published, a great deal of work had been done—and compiled in the first edition (published in 1988) of The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour. In it, Mike Fitzgerald, one of the world’s foremost experts on the subject, reviewed 61 predation studies, concluding:

“Predation on songbirds by domestic cats is noticed because it takes place during the day, whereas much predation on mammals takes place at night. People generally enjoy having songbirds in their gardens, and providing food in winter may increase the numbers of birds. When cats kill some of these birds, people assume that cats are reducing the bird populations. However, although this predation is so visible, and unpopular, remarkably little attempt has been made to assess its impact on populations of songbirds.” [7]

Two years later, Fitzgerald had a brief letter on the subject published in Environmental Conservation. His comments are as relevant today as they were some 21 years ago:

“Before embarking… on programmes to educate the public so that they will pressure elected officials to act on ‘cat delinquency,’ we must discover what effect domestic cats really have on the wildlife populations in various urban localities—not merely what effect we assume they have on the basis of prey brought home by cats in one English village. Although we know what prey cats bring home in a few urban localities, we do not know what effect this predation has on the prey populations, or how the wildlife populations might differ if cat populations were reduced. Until we have this information we cannot ensure sound educational programmes. We should perhaps also try to discover what values urban people place on their wildlife and their pets—it seems likely that many of the people who love their pets also treasure the wildlife.” [8]

Surely, Fitzgerald’s work would have been more appropriate for, and useful to, Ornithology’s audience. Instead, unsuspecting undergraduates were treated to biased editorializing dressed up as science.

Third Edition

Gill tells me I wasn’t the first to “react… to the Stallcup paper,” and that the push-back was sufficient to prompt its removal from the third edition. Gone, too, is Banks’ report. Instead, Gill employs the now-common kitchen-sink approach, rattling off a litany of sins—borrowed, it seems, from the American Bird Conservancy.

“Domestic house cats in North America, for example, may kill hundreds of millions of songbirds each year. Farmland and barnyard cats kill roughly 39 million birds (and lots of mice, too) each year. Millions of hungrier, feral (wild) cats add to this toll. There is a common-sense solution. Letting cats roam outside the house shortens their expected life span from 12.5 years to 2.5 years and increases their risk of rabies, distemper, toxoplasmosis, and parasites. Evidence is mounting that cats help to spread diseases such as Asian bird flu. The message is clear: Keep pet cats inside for their own well being and for the future of backyard birds (http://www.abcbirds.org/cats/).” [9]

That 39 million birds figure, of course, comes from the infamous “Wisconsin Study,” the authors of which claim: “The most reasonable estimates indicate that 39 million birds are killed in the state each year.” [10] (The “reason” is, in fact, notably absent from Coleman and Temple’s figure—which can be traced to “a single free-ranging Siamese cat” that frequented a rural residential property in New Kent County, Virginia. [11])

Its implied use as a nationwide estimate, Gill says, was “a lapse.” The more serious lapse by far, though—not in copyediting but in judgment—is Gill’s endorsement of ABC.

A Constructive Approach

While he readily admits that he’s “not tracked nor verified [ABC’s] stats (and have paid precious little attention to the issue for almost 10 years),” Gill’s support is unwavering.

“ABC has taken a lead role on the cat-bird issues, generally with a constructive approach, which I applaud, given how polarized the debates can be.”

Constructive? As I’ve pointed out repeatedly, no organization has been more effective at working the anti-TNR pseudoscience into a message neatly packaged for the mainstream media, and eventual consumption by the general public. (The Wildlife Society, though, which shares ABC’s penchant for bumper-sticker science and public discourse via sound-bites, is at least as eager to participate in the witch-hunt.)

Among the more glaring examples: senior policy advisor, Steve Holmer’s claim, quoted in the Los Angeles Times, that “there are about… 160 million feral cats [nationwide]” [12]; ABC’s promotion of “Feral Cats and Their Management,” with its absurd $17B economic impact “estimate,” published last year by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; and the numerous errors, exaggerations, and misrepresentations that persist in their brochure Domestic Cat Predation On Birds and Other Wildlife (PDF)—including a rather significant blunder that Ellen Perry Berkeley brought to light seven years ago in her book TNR Past, Present and Future. [13]

A constructive approach begins, by necessity, with sound science. But when it comes to the issue of free-roaming cats, at least, ABC has demonstrated neither an interest nor an aptitude.

So how does such an organization end up as the sole resource listed in a widely-used undergraduate textbook? (One written by the same man who served as the National Audubon Society’s chief scientist from 1996 to 2005, no less.) What’s next—physiology and nutrition books directing students to the PepsiCo Website for their hydration lesson? Psychology texts deferring to Pfizer (makers of Zoloft) on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors?

Frank Gill’s View

Gill never responded to my follow-up questions for this post. Still, his comments during our first exchange shed some light on his general attitude toward cats. “I have owned some wonderful (Siamese) cats in my life,” Gill explained, “so I do view them positively in many ways. But when they are dumped near a research station by returning vacationers and then eat the ringed birds I have been studying for many years, I take a different view.”

He followed this last sentence with a smiley-face emoticon, though the joke was clearly wasted on me.

“My informal view now is that managed feral cat colonies are potentially a serious threat to local bird populations, including both migrants that stopover in urban parks and endangered shorebird colonies. Sustaining those colonies should be prohibited generally. The return of coyotes to suburban landscapes is most welcome both to add a top predator to these ecosystems and to counter the numbers of feral cats as well as other midsized predators that impact breeding productivity. Just their presence in a neighborhood should persuade cat owners to keep their cats safely inside!”

• • •

It would be a mistake to suggest that the sloppy, flawed research I spend so much time critiquing can be traced directly to the second or third editions of Frank Gill’s textbook. Still, for many students, the path to a degree in ornithology (and onto related graduate degrees) leads through the book of the same name. As such, Ornithology may well be their first exposure to issues of population dynamics, conservation, and the like.

First impressions tend to be lasting ones. If, as a wide-eyed undergraduate, you “learned” that cats kill up to four million songbirds every day, how might that shape your future studies? Your career? What if you “learned” that such predation takes a $17B toll on the country annually?

Considering the tremendous burden we’re placing on future generations, why would we hobble them—before they even get started, really—with such misinformation and bias? They’ve got more than enough on their plate without having to fact-check their textbooks, too.

Literature Cited

1. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 1st ed. 1990, New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. 660.

2. Banks, R.C., Special Scientific Report—Wildlife No. 215. 1979, United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service: Washington, DC. p. 16.

3. Stallcup, R., “A reversible catastrophe.” Observer 91. 1991(Spring/Summer): p. 8–9. http://www.prbo.org/cms/print.php?mid=530

http://www.prbo.org/cms/docs/observer/focus/focus29cats1991.pdf

4. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 2nd ed. 1995, New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

5. Perry, G. Cats—perceptions and misconceptions: Two recent studies about cats and how people see them. in Urban Animal Management Conference. 1999.

6. Millwood, J. and Heaton, T. The metropolitan domestic cat. in Urban Animal Management Conference. 1994.

7. Fitzgerald, B.M., Diet of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York. p. 123–147.

8. Fitzgerald, B.M., “Is Cat Control Needed to Protect Urban Wildlife?“ Environmental Conservation. 1990. 17(02): p. 168-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900031970

9. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 3rd ed. 2007, New York: W.H. Freeman. xxvi, 758 p.

10. Coleman, J.S., Temple, S.A., and Craven, S.R., “Cats and Wildlife: A Conservation Dilemma.” 1997. http://forestandwildlifeecology.wisc.edu/wl_extension/catfly3.htm

11. Mitchell, J.C. and Beck, R.A., “Free-Ranging Domestic Cat Predation on Native Vertebrates in Rural and Urban Virginia.” Virginia Journal of Science. 1992. 43(1B): p. 197–207. www.vacadsci.org/vjsArchives/v43/43-1B/43-197.pdf

12. Yoshino, K. (2010, January 17). A catfight over neutering program. Los Angeles Times, from http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-feral-cats17-2010jan17,0,1225635.story

13. Berkeley, E.P., TNR Past present and future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement. 2004, Bethesda, MD: Alley Cat Allies.

Mother Jones, according to its Website, “is a nonprofit news organization that specializes in investigative, political, and social justice reporting.”

“…smart, fearless journalism” keeps people informed—“informed” being pretty much indispensable to a democracy that actually works. Because we’ve been ahead of the curve time and again. Because this is journalism not funded by or beholden to corporations. Because we bust bullshit and get results. Because we’re expanding our investigative coverage while the rest of the media are contracting. Because you can count on us to take no prisoners, cleave to no dogma, and tell it like it is. Plus we’re pretty damn fun.

Right up my alley. Until now.

With “Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!,” published in the July/August issue, articles editor Kiera Butler fails rather magnificently all the way around.

(The article isn’t available directly from MotherJones.com yet, but you can read it (print it, too) simply by signing up for the magazine’s e-mail updates. Enter your e-mail address and click “Sign Up.” In the next window, click on “ACCESS THE ISSUE NOW”—the full issue will then open automatically in Zinio, a digital magazine reader. “Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!” begins on p. 72.)

The title, by the way, comes from a 1965 cult classic in which “Three strippers seeking thrills encounter a young couple in the desert.” Sadly, the film is a better reflection of reality than the information in Butler’s article is.

Population of Cats

The most obvious blunder: Citing what seems to be the same data set (“the US feline population has tripled over the last four decades”) I referred to in my “Spoiler Alert” post, Butler arrives not at 90 million or so, as indicated in the original source [1], or even the bogus 150 million figure the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Tom Will tried to sell last year to the Bird Conservation Alliance.

No—according to Butler, there were 600 million cats in this country in 2007.

At that time, the human population was 301.3 million. For the sake of easy math, then, let’s call it two cats for every human (talk about “hip-deep in cats”!). This, I believe, sets a new record for absurd population claims—far surpassing the previous record held by Steve Holmer, senior policy advisor for the American Bird Conservancy.

And from here, it only gets worse. While her grossly inflated population figure might be attributed a simple mistake. These things happen (though, of course, one expects such things to be caught by somebody on the editorial staff). However, the misinformation, misrepresentations, and missteps that make up the bulk of “Faster, Pussycat!” betray either willful ignorance or glaring bias. Or both.

Smart, fearless journalism it is not.

One Billion Birds

Butler’s litany of complaints against feral cats is all too familiar: wildlife impacts (birds, in particular), public health threats, the “failures” of TNR, the powerful feral cat lobby, and the emotional/irrational nature of feral cat advocates (i.e., the classic “crazy cat lady” label). Her sources, too, include all the usual suspects; though few are cited, many others are obvious.

Sources of Mortality

Butler claims that domestic cats (“officially considered an invasive species”) top the list of mortality sources, killing perhaps one billion birds annually in the U.S. (Her tabulated comparison of seven mortality sources bears the familiar title “Apocalypse Meow.”)

The source of Butler’s “highest reliable estimates” is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, though the one-billion-birds claim has been made by others, including Nico Dauphine and Robert Cooper, [2, 3] and Rich Stallcup. [4] (In fact, Dauphine refers specifically to Stallcup’s wild-ass guess back-of-the-envelope calculation in her infamous “Apocalypse Meow” presentation.)

Yet even ABC, never one to go easy on cats—or to let science get in the way of their message—ranks building collisions ahead of cats. (Interestingly, neither USFWS nor ABC mentions the most direct human-caused source of bird mortality—hunting—which may account for 120 million avian deaths annually in the U.S. [5])

The one-billion-birds claim hinges upon an inflated estimate of outdoor cats (Dauphine and Cooper, for example, ignore published survey results [6–8], in effect doubling the number of pet cats allowed outdoors) and inflated predation rates (typically extrapolated from small, flawed studies). Multiplying one by the other, the result is impressive (hence, it’s “stickiness”).

Unfortunately, it’s also meaningless.

Still, such aggregate figures are useful for providing a scientific veneer to what is, at its core, little more than a witch-hunt. All of which makes it an easier sell to the media and the general public.

But sound bites ignore the importance of context. Aggregate predation rates, for example, fail to differentiate across vastly different habitats (e.g., islands, forests, coastlines, etc.), species (e.g., songbirds, seabirds, etc.), conditions (e.g., sick and healthy, young and old, etc.), and levels of vulnerability (e.g., ground-nesting and cavity-nesting species, rare and common species, etc.).

Predators—cats included—catch what’s easy. Indeed, at least two studies [9, 10] have found that cat-killed birds tend to be less healthy than those killed in non-predatory events (e.g., the other six mortality sources shown in Butler’s table).

Island Extinctions

In asserting that cats are “responsible for at least 33 avian extinctions worldwide,” Butler overlooks or ignores a critical detail: those extinctions involve primarily—perhaps exclusively—island species, with “insular endemic landbirds [being] most frequently driven to extinction” [11] And even this point is a matter of some debate. “Birds (both landbirds and seabirds) have been affected most by the introduction of cats to islands,” writes Mike Fitzgerald, one of the world’s foremost experts on the subject, “but the impact is rarely well documented.” [12]

“In many cases the bird populations were not well described before the cats were established and the possible role of other factors in changes in the bird populations are treated inadequately.” [12]

So what’s the impact of cats on continents?

In 2000, Fitzgerald and co-author Dennis Turner published a review of 61 predation studies, concluding unambiguously: “there are few, if any studies apart from island ones that actually demonstrate that cats have reduced bird populations.” [13]

Catbird Mortalities

Referring to research conducted by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center’s Peter Marra, Butler contends that “cats caused 79 percent of deaths of juvenile catbirds in the suburbs of Washington, DC.” In fact, Marra and his colleagues documented just six deaths attributable to cats, of 42 overall (then justified another three on dubious grounds). [14]

That 79 percent figure comes from dividing the number of deaths attributed to all sources of predation (33) by the total number of deaths documented over the course of the study (42). Butler’s misreading overstates predation by cats by more than 500 percent.

Public Health Threats

“Feral cats,” writes Butler, “can carry some heinous people diseases, including rabies, hookworm, and toxoplasmosis, and infection known to cause miscarriages and birth defects.” Her omission of infection rates—remarkably low in light of the frequent contact between humans and cats—suggests an interest more in fear-mongering than anything else.

Hookworms

A hookworm outbreak in the Miami Beach area in late 2010 made headlines, prompting officials to create a “cat poop map” (cats can pass hookworm eggs in their feces).

Meanwhile, Floridians were dying of influenza or pneumonia by the hundreds. In fact, according to the Florida Department of Health, 100–140 or so die each week during the winter months. (Actually, that figure accounts for only 24 of the state’s 67 counties, so the total is likely much higher.)

My point is not to dismiss the risk of “heinous people diseases” (or the suffering of those who become infected) but to put that risk into perspective. (In terms of public health, we’re better off focusing on frequent hand washing, sneezing into our sleeves, and, in the case of hookworms on the beach, wearing flip-flops—as opposed to, say, exterminating this country’s most popular companion animal by the millions.)

Toxoplasmosis

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Website, “Although cats can carry diseases and pass them to people, you are not likely to get sick from touching or owning a cat.” And, notes the CDC, “People are probably more likely to get toxoplasmosis from gardening or eating raw meat than from having a pet cat.”

(The same is true of feeding feral cats, by the way. While it’s true that their infection rates tend to be higher, [15] our frequent, close contact with pet cats more than offsets these differences.)

TNR

“In theory,” writes Butler, “TNR sounds great. If cats can’t reproduce, their population will decline gradually. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work. To put a dent in the total number of cats, at least 71 percent of them must be fixed, and they are notoriously hard to catch.”

In Los Angeles, adds Butler, “it failed miserably in the past.”

Contrary to Butler’s claims, however, there are numerous well-documented examples of TNR programs reducing colony size.

Perhaps the best-known TNR success story in this country is ORCAT. As of 2004, ORCAT, run by the Ocean Reef Community Association, had reduced its “overall population from approximately 2,000 cats to 500 cats.” [16] According to the ORCAT Website, the population today is approximately 350, of which only about 250 are free-roaming.

Other examples include a TNR program on the campus of the University of Florida University of Central Florida,

Orlando, in which caretakers found homes for more than 47 percent of the campus’ socialized cats and kittens, helping them reduce the campus cat population more than 66 percent, from 68 to 23. [17]

In North Carolina, researchers observed a 36 percent average decrease among six sterilized colonies in the first two years (even in the absence of adoptions), while three unsterilized colonies experienced an average 47 percent increase. [18] Four- and seven-year follow-up censuses revealed further reductions among sterilized colonies. [19]

A survey of caretakers in Rome revealed a 22 percent decrease overall in the number of cats through TNR, despite a 21 percent rate of “cat immigration.” [20]

And in South Africa, researchers recommended that “a suitable and ongoing sterilization programme, which is run in conjunction with a feral cat feeding programme, needs to be implemented” [21] on the campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Howard College—despite its proximity to “conservation-sensitive natural bush habitat and a nature reserve on the northern border.” [22]

The Cost of TNR

“Cash-strapped cities,” argues Butler, “can’t afford to chase down, trap, and sterilize every stray—a process that costs $100 per kitty.” So, can these cities afford to round up and kill the cats?

Mark Kumpf, past president of the National Animal Control Association doesn’t think so. “There’s no department that I’m aware of,” says Kumpf, “that has enough money in their budget to simply practice the old capture-and-euthanize policy; nature just keeps having more kittens.” Traditional control methods, he says, are akin to “bailing the ocean with a thimble.” [23]

The Cat Lobby

If TNR is so ineffective, why is it becoming the feral cat management approach of choice across the country (adopted in “at least 10 major cities,” according to Butler)? It must be the powerful cat lobby.

Alley Cat Allies, “whose budget was $5.3 million last year,” writes Butler, “has enjoyed generous grants from cat-food venders like PetSmart and Petco.”

It’s a play straight out of Dauphine’s playbook: paint the avian-industrial complex TNR opponents as victims of the powerful cat lobby. (In The Wildlife Professional’s recent special issue, “The Impact of Free Ranging Cats,” Dauphine complains: “The promotion of TNR is big business, with such large amounts of money in play that conservation scientists opposing TNR can’t begin to compete.” [24])

Alley Cat Allies

How generous were these grants, exactly? According to ACA’s 2010 Annual Report (PDF):

“Alley Cat Allies received more than $5.2 million in support between August 1, 2009 and July 31, 2010: more than 69,000 individuals contributed $4.8 million, including over $1 million in bequests. An additional $245,000 came from Workplace Campaigns, and over $14,000 came from foundation grants.”

Roughly 0.2 percent of their “total public support” came from all foundations combined. In 2009, grants and foundations accounted for 1.7 percent; in 2008, 1.0 percent. (Maybe Butler never got the memo re: MoJo’s commitment to bullshit-busting.)

New Jersey Audubon

Another of Dauphine’s complaints that found its way into “Faster, Pussycat!”:

“Pro-feral groups—there are 250 or so in the United States—have used their financial might to woo wildlife groups. Audubon’s New Jersey chapter backed off on its opposition to TNR in 2005, around the same time major foundations gave the chapter grants to partner with pro-TNR groups.”

What Butler (like Dauphine before her) fails to acknowledge is the important role NJAS plays in the New Jersey Feral Cat & Wildlife Coalition, which has developed a set of model protocols and ordinances designed to help municipal TNR programs in ensuring the protection of any vulnerable native wildlife (DOC).

This is exactly the kind of collaborative effort that should be supported.

For what it’s worth: it’s not clear that NJAS was easily wooed with grant funding. A quick visit to Guidestar.com reveals that NJAS brought in $6.8 million in 2008, and had $25.6 million in “net assets or fund balances” on its books. (I’ve been unable to determine the amount of grant funding NJAS received for “this important initiative,” as CEO and VP of Conservation and Stewardship Eric Stiles described it in a 2008 newsletter. [25])

Mental Health

Butler frames the TNR debate using what’s come to be standard form: rationale scientists on one side; on the other, cat advocates fueled by emotion. And mental illness, too, apparently: “There’s also speculation that [toxoplasmosis] can trigger schizophrenia and even the desire to be around cats—some researchers blame the crazy-cat-lady phenomenon on toxo.”

A Heated Debate

It’s a dangerous combination, according to Butler.

“Many of the biologists I spoke with say they’ve been harassed and even physically threatened when they’ve presented research about the effect cats have on wildlife.”

Is it really so one-sided?

Why didn’t Butler mention the case of Jim Stevenson, the Galveston birder who, in 2006, shot and killed (though not immediately) a feral cat within earshot of the cat’s caretaker? [26]

Or, more recently, the charges of attempted animal cruelty filed by the Washington Humane Society against Dauphine? (Or, for that matter, the stream of toxic comments almost guaranteed to accompany nearly any online story about feral cats or TNR.)

Clearly, the “cat people” don’t have a monopoly on emotional—even violent—responses to the issue.

Sustaining a Killer

When Butler tells an ecologist she knows that she’s feeding a feral cat, she’s told: “Basically, you’re sustaining a killer.” Which is essentially Butler’s intended take-away:

“Until they do [invent a single-dose sterilization drug], biologists recommend a combination of strategies. For starters, quit feeding ferals: Beyond sustaining strays, the practice often leads to delinquent pet owners to abandon their cats outdoors, assuming they will be well cared for.”

Are we to believe that abandonment is reduced or eliminated where the feeding of feral cats is prohibited? Owners (delinquent, I agree) interested in dumping their cats can, unfortunately, do so easily.

The far greater incentive for dumping comes from local shelters, most of which euthanize kill the majority of cats brought in. Many require a surrender fee.

I’m just about the last person to defend the dumping of cats, but shouldn’t we acknowledge the aspects of “animal control” policy that contribute to it?

But back to this idea that “no food” means “no ferals.” It sounds reasonable enough, but doesn’t hold up very well to scrutiny. For one thing, where there are humans, there’s food to be found. In fact, even where there are no people, cats don’t starve.

On Marion Island—barren and uninhabited—it took 19 years to eradicate approximately 2,200 cats. Their only human provision: “the carcasses of 12,000 day-old chickens” each injected with the poison sodium monofluoroacetate. [27] (The rest—the vast majority—were killed through the introduction of feline distemper, intensive hunting and trapping, and dogs. [28, 27])

Is Butler suggesting that the cats in her neighborhood would have it tougher than the Marion Island cats? Even setting aside the cruelty involved, we’re not likely to starve our way out of the “feral cat problem.” Unlike TNR, such an approach only drives the cats (and their caretakers) underground.

This, of course, is roughly the same approach that’s proved ineffective failed so spectacularly at addressing so many other complex issues, including drug enforcement, immigration policy, gays in the military, and so forth.

• • •

Since I launched Vox Felina last year, I’ve been critical of articles appearing in any number of publications: scientific journals (e.g., Conservation Biology), major newspapers (e.g., The Washington Post and The New York Times), an alt-weekly, and more.

None of which bothered me in the least, as I feel no particular connection to any of them. This is not to say that I don’t value, admire, and respect much of the work found, for instance, in the Times—only that I’ve no affinity for, or loyalty to, the paper itself.

But Mother Jones is different. Maybe it’s that whole bullshit-busting, take-no-prisoners, tell-it-like-it-is business—I’d like to think that’s something we share in common.

This time around, though, the magazine served up bullshit by the shovelful, swallowed in one gulp the misinformation churned out by ABC, The Wildlife Society, and other TNR opponents, and… well, told it like it isn’t.

With the publication of “Faster, Pussycat!,” Mother Jones failed miserably in its promise to readers. Which, I have to think, isn’t a lot of fun.

Literature Cited

1. Lepczyk, C.A., et al., “What Conservation Biologists Can Do to Counter Trap-Neuter-Return: Response to Longcore et al.” Conservation Biology. 2010. 24(2): p. 627–629. www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/pdf/Lepczyk-2010-Conservation%2520Biology.pdf

2. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2009. p. 205–219. http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/pif/pubs/McAllenProc/articles/PIF09_Anthropogenic%20Impacts/Dauphine_1_PIF09.pdf

3. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., “Pick One: Outdoor Cats or Conservation.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 50–56.

4. Stallcup, R., “A reversible catastrophe.” Observer 91. 1991(Spring/Summer): p. 8–9. http://www.prbo.org/cms/print.php?mid=530

http://www.prbo.org/cms/docs/observer/focus/focus29cats1991.pdf

5. Klem, D., “Glass: A Deadly Conservation Issue for Birds.” Bird Observer. 2006. 2. p. 73–81. http://www.massbird.org/BirdObserver/index.htm

6. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.1541

7. Lord, L.K., “Attitudes toward and perceptions of free-roaming cats among individuals living in Ohio.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2008. 232(8): p. 1159-1167. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_232_8_1159.pdf

8. APPA, 2009–2010 APPA National Pet Owners Survey. 2009, American Pet Products Association: Greenwich, CT. http://www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp

9. Møller, A.P. and Erritzøe, J., “Predation against birds with low immunocompetence.” Oecologia. 2000. 122(4): p. 500–504. http://www.springerlink.com/content/ghnny9mcv016ljd8/

10. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: Is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86–99. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bsc/ibi/2008/00000150/A00101s1/art00008

11. Nogales, M., et al., “A Review of Feral Cat Eradication on Islands.” Conservation Biology. 2004. 18(2): p. 310–319. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00442.x/abstract

12. Fitzgerald, B.M., Diet of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York. p. 123–147.

13. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

14. Balogh, A., Ryder, T., and Marra, P., “Population demography of Gray Catbirds in the suburban matrix: sources, sinks and domestic cats.” Journal of Ornithology. 2011: p. 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0648-7

http://nationalzoo.si.edu/scbi/migratorybirds/science_article/pdfs/55.pdf

15. Dubey, J.P. and Jones, J.L., “Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and animals in the United States.” International Journal for Parasitology. 2008. 38(11): p. 1257–1278. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4S85DPK-1/2/2a1f9e590e7c7ec35d1072e06b2fa99d

16. Levy, J.K. and Crawford, P.C., “Humane strategies for controlling feral cat populations.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1354–1360. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/default.asp

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1354.pdf

17. Levy, J.K., Gale, D.W., and Gale, L.A., “Evaluation of the effect of a long-term trap-neuter-return and adoption program on a free-roaming cat population.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(1): p. 42-46. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.42

18. Stoskopf, M.K. and Nutter, F.B., “Analyzing approaches to feral cat management—one size does not fit all.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1361–1364. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552309

www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1361.pdf

19. Nutter, F.B., Evaluation of a Trap-Neuter-Return Management Program for Feral Cat Colonies: Population Dynamics, Home Ranges, and Potentially Zoonotic Diseases, in Comparative Biomedical Department. 2005, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC. p. 224. http://www.carnivoreconservation.org/files/thesis/nutter_2005_phd.pdf

20. Natoli, E., et al., “Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy).” Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2006. 77(3-4): p. 180–185. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TBK-4M33VSW-1/2/0abfc80f245ab50e602f93060f88e6f9

www.kiccc.org.au/pics/FeralCatsRome2006.pdf