Although it’s taken me two months to respond, it took less than two weeks for Vox Felina to come under attack by feral cat/TNR opponent Michael Hutchins, CEO and Executive Director of The Wildlife Society. In his post, Hutchins accuses me of trying to “out-science the scientists,” and refers to my critique of the essay “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap-Neuter-Return” as “a flawed analysis, which could have been written by a high school biology student, and not a very good one at that.”

Hutchins goes on to write:

“Unless the author, who is obviously not a trained scientist himself, can publish a strong and verifiable critique of the Longcore et al. paper in the peer-reviewed wildlife biology/ecology literature, all of his arguments must be taken with a gigantic grain of salt.”

In the weeks since Hutchins’ post, I’ve gone to some length to point out some of the more blatant instances of errors, misrepresentations, and bias in the wildlife biology/ecology literature he defends. As this seven-part series, called “The Work Speaks,” (beginning with this post) makes clear, Hutchins’ had better have plenty more salt on hand as he reviews the work of his colleagues.

In the interest of transparency, then, here is my response—as an open letter—to Hutchins’ May 3rd post:

Dear Michael,

Let me begin by introducing myself. My name is Peter J. Wolf, and I’m the writer behind the Vox Felina blog. I’d like to address some of the points you made in your May 3rd critique of my work. (In the interest of transparency, this letter will be posted in its entirety on my blog.)

By way of clarification, you referred to me in your post as “the author, who is obviously not a trained scientist himself.” In fact, my training is in mechanical engineering and qualitative research methods. That said, does it require a trained scientist to point out the numerous flaws in the anti-feral cat/TNR literature—to, if I might borrow from the title of your post, out-science the scientists? I don’t think so. Indeed, some of your colleagues—including those you defend—have set an astonishingly low bar. Consider, for example, some of the issues I’ve addressed in my recent posts:

- When did it become acceptable to cite work one hasn’t actually read? As I pointed out in “Lost in Translation,” this seems to be surprisingly common. Nico Dauphiné and Robert Cooper, for example, are just the latest to get William George’s classic 1974 study [1] wrong. George never “found that only about half of animals killed by cats were provided to their owners,” [2] as these two authors suggest. This is an error—and an all-too-tempting-shortcut to the doubling of predation rates—that, as Fitzgerald noted 10 years ago, “has been reported widely, though it is unfounded.” [3] (Of course, if Dauphiné and Cooper aren’t reading George’s work—which they cite—I don’t imagine they’d bother with Fitzgerald’s—which they don’t even mention.)

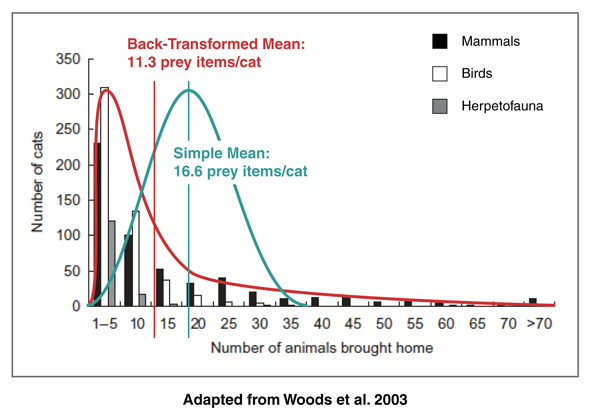

- Are scientists no longer expected to recognize and deal appropriately with non-normal data sets, such as the positively skewed distributions that describe prey catches, cat ownership, time spent outdoors by pet cats, and more? As I describe in “Mean Spirited,” this seems to be the exception, not the rule. Using simple averages overestimates the factor in question, and in turn, the impact of free-roaming cats on wildlife. Such errors increase rapidly when one is multiplied by another, as Christopher Lepczyk demonstrated in his PhD work. [4]

- While we’re on the subject of statistics, what about appropriate sample sizes? This was the focus of my 27-May post, “Sample-Minded Research.” Among the examples I discussed was Kays and DeWan’s misguided conclusion that the actual “kill rate” of pet cats allowed access to the outdoors is “3.3 times greater than the rate estimated from prey brought home.” [5] This “correction” factor has been used by many [2, 6–8] as another easy multiplier, despite the fact that it’s based on the behavior of just 24 cats—12 that returned prey home, and another 12 that were observed hunting for a total of 181 hours.Even setting aside the size of the samples, their dissimilarities are striking: the cat observed the most (46.5 hours) was only a year old—the youngest of the 12 observed, and therefore likely to be the most active hunter. In addition, larger, more comparable samples would probably have revealed a profile of time spent outdoors more similar to those found in other studies [9] and [10] (thereby reducing the magnitude of Kays and DeWan’s error).

- And finally, there’s the issue of how some of these studies are designed. Take Cole Hawkins’ PhD work, for example. Hawkins compares rodent and bird numbers between two areas, and draws conclusions—infers important causal relationships—without (1) taking into account various factors (e.g., the many differences between the two study areas) that likely affected the differences he observed, and (2) any evidence of what “pre-treatment” conditions were like. Although he concludes, “the differences observed in this study were the results of the cat’s predatory behavior,” [11] he offers no explanation for the numerous exceptions—for example, the five (of nine) species of ground-feeding birds that showed no preference for the “no-cat area” over the area with cats. Lepcyzk, too, started off his PhD work on shaky ground, asking owners of cats to recall the number and species of birds killed or injured by their cats over the previous six-month period. Five years earlier, David Barratt demonstrated that such guesswork tends to overestimate predation rates—perhaps by a factor of two or more. [12]

In your post, you write:

“One goal of the peer review process is to assess an author’s command of the existing literature and whether or not it is being cited selectively to support the author’s views, without critical evaluation of contradictory evidence.”

But the essay you defend is plagued by such “selective support.” For example, Longcore et al. trot out figures from the long-discredited (and non-peer-reviewed, by the way) Wisconsin Study. In 1994, co-author Stanley Temple told the press that their estimates “aren’t actual data; that was just our projection to show how bad it might be.” [13] But 16 years later, Longcore et al. seem to be suggesting otherwise—that these figures are actual data. By publishing these deeply flawed estimates, the authors—and, by extension, Conservation Biology—give them undeserved credibility.

Longcore et al. also give too much weight to the claim made by Baker et al. that cat predation may produce a habitat sink, [6] ignoring strong evidence that the predation observed was compensatory rather than additive [7, 14] (as well as the significant flaws in their estimates of predation rates/levels). In this case, the contradictory evidence you refer to was provided by the authors of the original study, and still, Longcore et al. fail to acknowledge it—never mind offer any critical evaluation. Indeed, they fail to acknowledge any distinction between the two types of predation—a critical point in the discussion of cat predation and its impact on wildlife.

And what about the authors’ reference to the 2003 paper by Lepczyk et al. as evidence that “cats can play an important role in fluctuations of bird populations”? [15] One might get that impression from the paper’s abstract. However, the study’s focus was—as Lepczyk et al. note themselves—on cat predation, not bird populations:

“Although our research highlights a number of important findings regarding outdoor cats, there remains many aspects that are in need of further research… conservation biologists lack data on how specific levels of cat predation depress wildlife populations and if there are thresholds at which cat densities become a biologically significant source of mortality.” [4]

Somehow, all of this (and much more) survived the peer-review process you so revere—a system whose failures have been made quite public over the past eight months or so, first, when climate scientists’ e-mail messages were hacked at a British university, and later, when the Lancet retracted a 1998 paper incorrectly linking vaccinations to autism in children.

Obviously, these are spectacular cases. But if such high-profile work can be published and circulated widely, then how much easier is it for other papers—facing far less scrutiny—to do so as well?

Scientific Publications and the Peer-Review Process

I find your criticism ironic—even hypocritical—in light of the Scientific Societies’ Statement on the Endangered Species Act you co-authored in 2006. There, you acknowledged the value of the peer-review process, but also cautioned that “proposed limitations on the use of non-peer-reviewed technical reports and other studies will weaken, not strengthen, the science employed in endangered species decisions by limiting the data available to scientists and decision-makers.” Can we not make a similar argument for critiques and reviews such as those I’ve carefully composed and compiled via Vox Felina?

It’s curious that neither you nor the editors at Conservation Biology actually dispute any of the claims I’ve made regarding the flaws in “Critical Assessment.” Instead, you call my work “vaguely scientific” and “editorializing,” ultimately dismissing it because of its lowly status as a blog (“clearly not the place that the debate should occur”).

This is quite a departure from the position you took just four years ago. Rather than advocating for rigorous scientific discourse—regardless of a particular work’s origin—you’re now putting publication above all else. Would you suggest, for example, that using means to describe highly skewed populations—because such practice has been published in peer-reviewed journals—is appropriate and acceptable? And, further, that my calling these researchers on the carpet for it—because I’ve done it via a blog—is somehow invalid? Or that the predation rates proposed in the Wisconsin Study have merit?

The same can be said for the numerous issues I’ve covered in the past several weeks (many of which I’ve outlined above): if I’m right, then I’m right; if I’m wrong, then I’m wrong. In the end, it shouldn’t matter whether these critiques are published in a peer-reviewed journal, posted at Vox Felina, or scribbled on the back of a cocktail napkin. What matters is simply whether the points I’ve made are valid or not.

It’s difficult not to see a certain irony in your immediate and wholesale dismissal of my work—based only on the first of a four-part series (and clearly “advertised” as such). You’re quick to criticize, for example, my apparent failure to “address any of the more recent work that Longcore et al. relied on, or that have subsequently been published.” I wonder: did you bother to read any of my subsequent posts, in which I addressed these points at some length? As a trained scientist, wouldn’t you want to see all the “data” before drawing your conclusions? Your post has done far more to highlight the need for Vox Felina than to discredit it.

Don’t get me wrong—I’ve nothing against criticism; indeed, that’s the very premise of Vox Felina. But, before rendering judgment, you owe it to your readers, your colleagues, and yourself to at least have all the relevant information in front of you. This, it seems to me, is a necessary first step not only for scientific discourse, but for any civil discourse.

Los Angeles Court Case

With regard to the injunction against publicly supported TNR in Los Angeles, you’re correct in noting that the case was not about the efficacy of TNR. However, there’s far more science in the administrative record than you suggest. Though the majority of the record is made up of e-mail communications, trapping permits, and the like, it is peppered throughout with various papers, reports, and numerous references to scientific literature.

To take just one example, there’s this excerpt from a letter dated March 27, 2006 by Babak Naficy, the attorney representing the Urban Wildlands Group and the American Bird Conservancy:

“A decision by the Commission to implement the TNR policy will likely result in an increase in the population of feral cats in the City by returning feral cats to the environment that otherwise would be taken into shelters, and by issuing permits to maintain feral cat colonies. Notwithstanding the goal of the project to reduce feral cat numbers, TNR programs are less effective than removal in controlling feral cat populations, [16] and consequently this shift in policy would increase the number of feral cats in the environment. As has been communicated to the Commission by my clients in the past, it is well settled that feral and domestic cats adversely affect the population of songbirds and other small animals, such as small mammals and lizards. [11] Furthermore, the scientific literature shows that TNR is not effective in decreasing the number of feral cats on a regional basis. [17] An intensive TNR program combined with cat adoption at a Florida university took 11 years to reduce a county by two-thirds (6% per year), and even then animals continued to be abandoned and added to the colony.” [18]

“Additionally, City-endorsed feral cat colonies present a severe public health risk, [19] especially to vulnerable human populations such as the homeless. Maternal exposure to toxoplasmosis, often carried by feral cats, increases risk of schizophrenia in humans. [20] Therefore, any decision that mandates return of unowned cats to the environment may increase the number of free-roaming cats in the City and will likely result in a concomitant adverse impact on the environment.”

That said, perhaps I was not clear in my post. I was not implying any direct connection between the Longcore et al. paper and the Los Angeles TNR case (e.g., that the paper itself was part of the administrative record). The point I was trying to make was that the Urban Wildlands Group—lead petitioner in the case—was not a disinterested party concerned with science for its own sake. Longcore et al. were key stakeholders—focused, it seems, more on their “message” (the timing of which was itself uncanny) than the validity of any scientific claims.

And in any event, I don’t see how the case can be so easily divorced from science. This is not about property rights or tax code. Its status as a California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) case presupposes the possibility of “either a direct physical change in the environment or a reasonably foreseeable indirect change in the environment.” The evidence of such changes, of course, would rely on scientific research. As I say, the administrative record contains numerous claims regarding potential impacts and the studies supporting or refuting them. Whether the judge in the case allowed this material to influence his eventual decision is unknown; but it’s clear from court transcripts that he considered it quite relevant:

“Look, you put feral cats in the wild, they endanger wildlife. That is an environmental concern…”

“It doesn’t affect birds? It doesn’t affect other wildlife? A fair argument has been made that it does. A fair argument… a fair argument has been made that when you take them out of the wild—not all of them are taken out of wild—but you take 50,000 cats out of the wild and do not consider other alternatives such as euthanizing them and return them back to the wild, I would be embarrassed to stand there and argue that there is no environmental effect… so you bring them in, you neuter the them and you put them out, and they endanger other wildlife and perhaps health and a lot of other issues that come to bear, and that’s the only consideration made and that’s not a project. Please, spare me.”

“And who is to go out and if the feral cats are running wild, does the Animal Services have a program to round up a herd of cats, if that’s possible—that’s an old expression—and bring them in a neuter them and let these little kitties out to kill birds and other wildlife?”

Whether or not Los Angeles had an official TNR program in place may have been at the center of the case, but it was certainly not the whole case.

Compromise, Courage, and Leadership

As I’ve noted on Vox Felina’s About page, there are legitimate issues to be debated regarding the efficacy, environmental impact, and morality of TNR. But attempts at an honest, productive debate are hampered—if not derailed entirely—by the dubious claims so often put forward by TNR opponents. Exactly the sort of claims I’ve attempted to untangle over the past several weeks.

But from what I’ve read of your work, you don’t seem interested in such a debate, and even less interested in finding common ground:

“Cooperation and compromise, no matter what the cost, is not courageous leadership.” [21]

Perhaps it’s impressive as rhetoric, but your comments strike me as somewhat hypocritical (your attempt to make a virtue of the same ideological inflexibility you dismiss in the animal rights community), misguided, and, in the end, simply unhelpful. More worrisome, however, is your willingness to let your ideology blind you to the numerous errors in the work you so vigorously defend.

Michael, how can you expect so much courage and leadership from your colleagues when you demand so little honesty and integrity?

Peter J. Wolf

www.voxfelina.com

Literature Cited

1. George, W., “Domestic cats as predators and factors in winter shortages of raptor prey.” The Wilson Bulletin. 1974. 86(4): p. 384–396.

2. Dauphiné, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2009. p. 205–219.

3. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

4. Lepczyk, C.A., Mertig, A.G., and Liu, J., “Landowners and cat predation across rural-to-urban landscapes.” Biological Conservation. 2003. 115(2): p. 191-201.

5. Kays, R.W. and DeWan, A.A., “Ecological impact of inside/outside house cats around a suburban nature preserve.” Animal Conservation. 2004. 7(3): p. 273-283.

6. Baker, P.J., et al., “Impact of predation by domestic cats Felis catus in an urban area.” Mammal Review. 2005. 35(3/4): p. 302-312.

7. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86-99.

8. van Heezik, Y., et al., “Do domestic cats impose an unsustainable harvest on urban bird populations?“ Biological Conservation. 143(1): p. 121-130.

9. ABC, Human Attitudes and Behavior Regarding Cats. 1997, American Bird Conservancy: Washington, DC. http://www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/materials/attitude.pdf

10. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545.

11. Hawkins, C.C., Impact of a subsidized exotic predator on native biota: Effect of house cats (Felis catus) on California birds and rodents. 1998, Texas A&M University

12. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by house cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. II. Factors affecting the amount of prey caught and estimates of the impact on wildlife.” Wildlife Research. 1998. 25(5): p. 475–487.

13. Elliott, J., The Accused, in The Sonoma County Independent. 1994. p. 1, 10

14. Møller, A.P. and Erritzøe, J., “Predation against birds with low immunocompetence.” Oecologia. 2000. 122(4): p. 500-504.

15. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap–Neuter–Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894.

16. Andersen, M.C., Martin, B.J., and Roemer, G.W., “Use of matrix population models to estimate the efficacy of euthanasia versus trap-neuter-return for management of free-roaming cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(12): p. 1871-1876.

17. Foley, P., et al., “Analysis of the impact of trap-neuter-return programs on populations of feral cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2005. 227(11): p. 1775-1781.

18. Levy, J.K., Gale, D.W., and Gale, L.A., “Evaluation of the effect of a long-term trap-neuter-return and adoption program on a free-roaming cat population.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(1): p. 42-46.

19. Patronek, G.J., “Free-roaming and feral cats—their impact on wildlife and human beings.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1998. 212(2): p. 218–226.

20. Brown, A.S., et al., “Maternal Exposure to Toxoplasmosis and Risk of Schizophrenia in Adult Offspring.” Am J Psychiatry. 2005. 162(4): p. 767-773.

21. Hutchins, M., “Animal Rights and Conservation.” Conservation Biology. 2008. 22(4): p. 815–816.