Complaining of the impacts of free-roaming cats on wildlife and the environment, along with a range of public health threats, dozens of veterinarians in Hillsborough County, Florida, have banded together to fight TNR. Evidence suggests, however, that their real concern has nothing to do with the community, native wildlife, or, indeed, with cats. What the Hillsborough Animal Health Foundation is most interested in protecting, it seems, is the business interests of its members.

In Part 2 of this five-part series, I use Florida Department of Heath data for rabies cases (in animals) and possible rabies exposures (humans) to challenge HAHF’s claim that free-roaming cats pose a significant rabies threat.

The “trouble with trap-neuter-re(abandon!),” as the Hillsborough Animal Health Foundation explains on its website, “is simply stated by the executive summary of the 2012 Florida Department of Health Rabies Guide.”

“The concept of managing free-roaming/feral domestic cats (Felis catus) is not tenable on public health grounds because of the persistent threat posed to communities from injury and disease. While the risk for disease transmission from cats to people is generally low when these animals are maintained indoors and routinely cared for, free-roaming cats pose a continuous concern to communities. Children are among the highest risk for disease transmission from these cats.” [1]

“Veterinarians are legally required to follow the Rabies Guide,” argues HAHF. “As a result, we are gravely concerned about Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR), and the implications of any such county funded or endorsed program.”

But if TNR truly increases the risk of rabies exposure, what difference does it make where the funding comes from? (I’ll get into that in Part 5.)

In any case, veterinarians are legally required to follow the law.

And while the Rabies Guide (PDF), issued by the Florida Department of Health, cites a variety of statutes, codes, and ordinances—in addition to multiple references to the “legislative authority” granted the Florida DOH—it’s curious that the publication doesn’t actually refer to any law prohibiting “the concept of managing free-roaming/feral domestic cats.” (In fact, the entire section covering free-roaming cats is of such poor quality—claims directly contradicting CDC data and reports, for example, and its failure to acknowledge the potential for TNR to provide a rabies barrier between wildlife and humans [2]—one wonders about the motivation of its authors. Perhaps I’ll tackle this in a future post.)

Humans (Possibly) Exposed to Rabies

“More than 2,000 people were exposed to rabid or potentially rabid animals in Florida in 2010,” explains HAHF. “This represents a 46 percent increase over the five-year average, and cats represented 25 percent of the incidents.” In fact, the increase was—according to the very report HAHF cites—actually 41.33 percent, with cats representing 24 percent of “exposed persons for whom treatment was recommended.” [3] But that’s quibbling, I suppose.

What’s far more interesting is how HAHF chose to “edit” their summary of the Florida DOH report, which is worth quoting at length:

“In 2001, reporting of animal encounters for which rabies post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is recommended was initiated. Rabies PEP is recommended when an individual is bitten, scratched, or has mucous membrane or fresh wound contact with the saliva or nervous tissue of a laboratory-confirmed rabid animal, or a suspected rabid animal that is not available for testing. The annual incidence of exposures PEP is recommended has increased since case reporting was initiated. In 2010, the incidence rate was up 41.33 percent over the previous five-year average although the number of confirmed rabid animals decreased in 2010 compared to 2009. This increase in PEP may be due to improved reporting, increased exposures to possible rabid animals, increased inappropriate or unnecessary use of PEP, or a combination of factors. Reductions in state and local resources may contribute to increases in inappropriate or unnecessary use of PEP by decreasing resources to investigate animal exposures and confirm animal health status, and by reducing county health department staff time to provide regular rabies PEP education for health care providers.” [3, emphasis mine]

(As I pointed out in my previous post, HAHF may very well be contributing to the “increased inappropriate or unnecessary use of PEP” with all their scaremongering.)

Suddenly, what seems like a dramatic uptick in rabies exposure—one in which HAHF suggests cats played a key role—looks more like what it is: the result of several poorly understood (and, in some cases, competing) factors. Puzzling, but hardly the public health threat suggested by HAHF.

Interestingly, dogs were implicated in 46 percent of PEP incidents, nearly twice as many as were cats. And, 75 percent of the owned animals (which made up 20 percent of the total) involved in the 2,114 exposures that occurred in 2010 were pet dogs. [3] My point is not to shift attention to dogs, but simply to add a little perspective. One would expect HAHF—as members of the veterinarian community concerned for “our precious children”—to at least acknowledge the point.

Instead, HAHF quotes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: “In 2009, rabies cases among cats increased for the second consecutive year. Three times more rabid cats were reported than rabid dogs.” Which is true—but also misleading. As a report of CDC data makes clear: “differences in protocols and submission rates among species and states [make] comparison of percentages of animals with positive results between species or states… inappropriate.” [4]

In other words, the rabies surveillance data at the heart of all these claims are not an accurate reflection of rabies prevalence in the population of any particular species. The low numbers for bobcats in Florida (just 44 across 20 years), for example, are likely a reflection of this cat’s relatively few encounters with humans as much as anything else.

Some additional perspective: since 1960, only two cases of human rabies in the U.S. have been attributed to cats. [5]

The Risks to Children

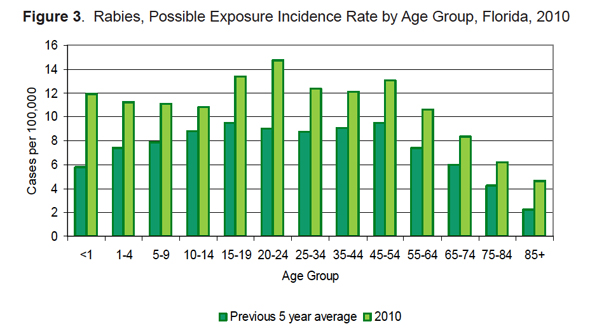

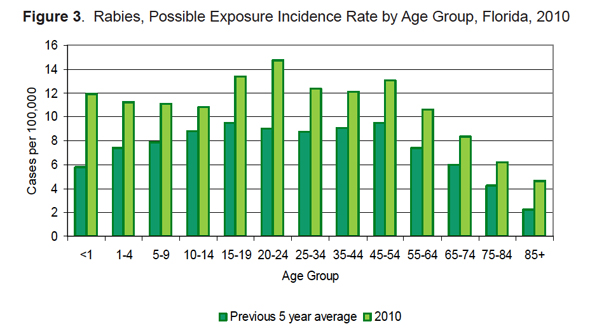

Contrary to the claims made in the Florida DOH Rabies Guide (“Children are among the highest risk for disease transmission from [free-roaming] cats.”) and on the HAHF website (“a large burden of the [public health] risk lies against our precious children!”), Florida DOH data suggest that the only age group less likely to be exposed to rabies is adults 55 and older. According to the 2010 Florida Morbidity Statistics Report (from which the chart below was taken):

“The average age of the victim for the 2,114 cases reported in 2010 was 37 years, with a range from under one year to 110 years of age. The highest incidence was seen in individuals aged between 20 and 24 years, but incidence was similar for ages 15 to 19 and 45 to 54 years. There were some variations in age based on the type of animal involved. Average age for those recommended to receive PEP who were exposed to dogs was 32 years; cats, 41 years; and wildlife, 43 years.” [3, emphasis mine]

Rabid Animals

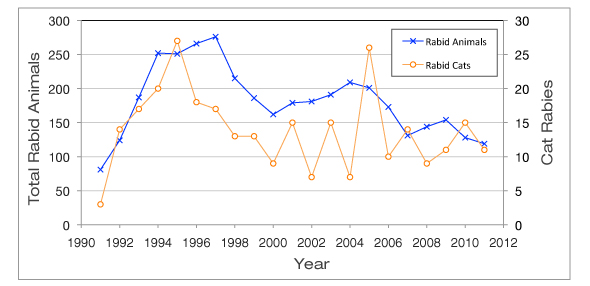

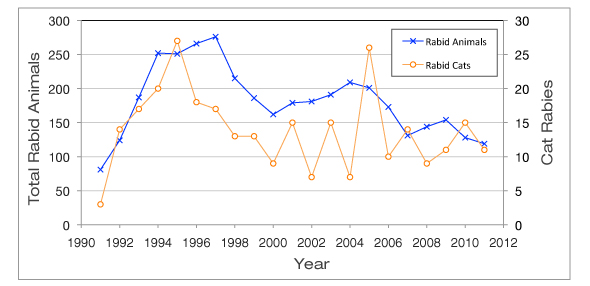

It’s perfectly understandable for public health officials to focus on possible exposure and PEP incidents—but it’s also worth looking at the data documenting confirmed cases of rabid animals in Florida and Hillsborough County. (Tampa Bay Online has developed a handy interactive state map of 2006–09 rabies cases.) Doing so reveals a steady downward trend since the mid-1990s* at both the state [6] and county levels, [7] as indicated in the graphs below.

The trend is even more striking when one considers Florida’s population explosion over the same period, from 12,937,926 in 1990 to 18,801,311 in 2010, an increase of 45 percent. More people means more pets—as well as the kinds of interactions with wildlife that lead to increased surveillance reporting.

Now, I’m not prepared to attribute the notable downturn in rabies cases—in cats and in animals overall—to TNR. There are simply too many factors involved. On the other hand, the trend challenges the assertion made by HAHF (and the Florida DOH in its Rabies Guide) that TNR—which has become increasingly popular over the past 20 years—leads to an increased risk of rabies exposure.

• • •

*The data suggest that the sharp increase during the early 1990s was due to an increase in rabies cases among the state’s raccoon population.

Coming up:

• Part 3: Toxoplasmosis prevalence

• Part 4: Hillsborough County Animal Services: Past, Present, and Future

• Part 5: Would the real HAHF please stand up?

Literature Cited

1. n.a., Rabies Prevention and Control in Florida, 2012. 2012, Florida Department of Health: Tallahassee, FL. www.myfloridaeh.com/newsroom/brochures/rabiesguide2012.pdf

2. Clifton, M. (2010). How to introduce neuter/return & make it work. Animal People, pp. 3–4, from http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/10/4/April10.htm

3. n.a., 2010 Florida Morbidity Statistics Report. 2011, Florida Department of Health, Division of Disease Control, Bureau of Epidemiology: Tallahassee, FL. http://www.doh.state.fl.us/disease_ctrl/epi/Morbidity_Report/2010/2010_AMR.pdf

4. Blanton, J.D., et al., “Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2008.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2009. 235(6): p. 676–689. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19751163

www.avma.org/avmacollections/rabies/javma_235_6_676.pdf

5. n.a., “Recovery of a Patient from Clinical Rabies—California, 2011.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012. 61(4): p. 61–64. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6104a1.htm

6. n.a., 20 Year Animal Rabies Summary by Species (1991–2010) 2011, Florida Department of Health: Tallahassee, FL. http://www.doh.state.fl.us/environment/medicine/rabies/Data/2010/Rabies20YrTable91_10.pdf

7. n.a. Rabies Surveillance: Charts, Maps, and Graphs. 2006 [cited 2012 August 25]. http://www.doh.state.fl.us/Disease_ctrl/epi/rabies/chart.html.