“SF Weekly is San Francisco’s smartest publication. That’s because we take journalism seriously, but not so seriously that we let ourselves be guided by an agenda.”

At least that’s what the paper’s Website says.

Now, as somebody who reads SF Weekly only rarely, I want to be careful not to generalize. But if last week’s feature story is typical, then it’s time for the paper to update either its About page or its editorial standards.

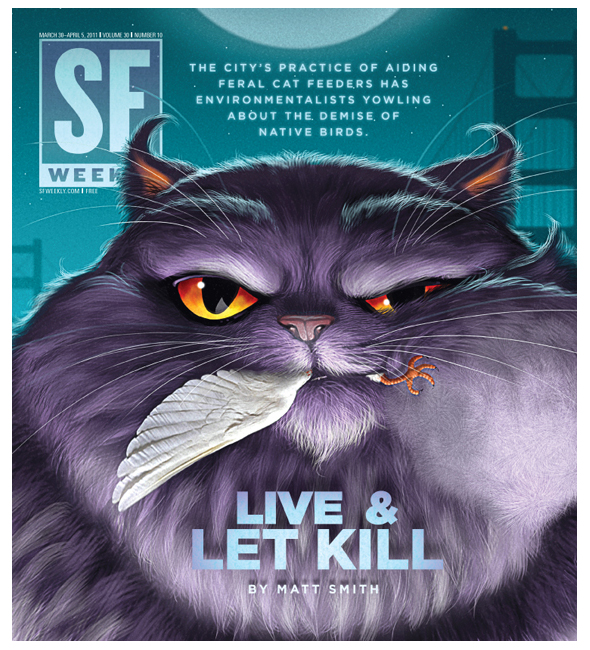

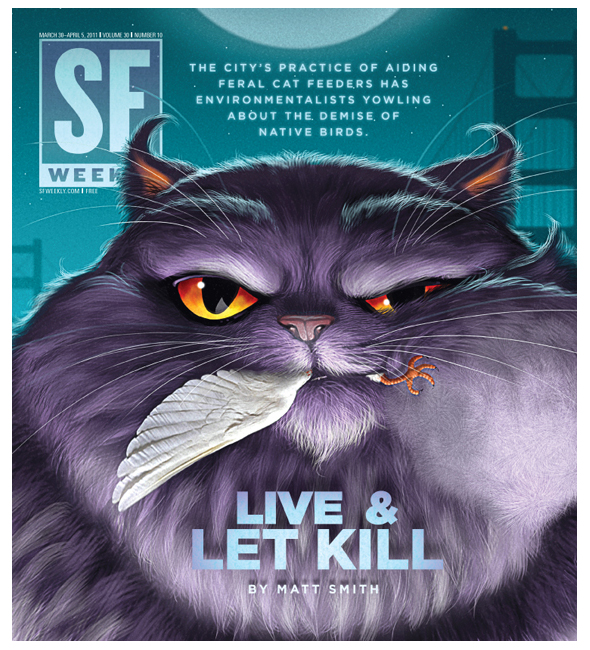

“Live and Let Kill” isn’t particularly smart. And, as journalism, it falls well short of the “serious” category.

Reporter Matt Smith argues that “greater scrutiny may be just what the feral feeding movement needs,” while he swallows in one gulp the numerous unsubstantiated claims made by TNR opponents.

Indeed, Smith pays more attention to colony caretaker Paula Kotakis’ “cat-hunting outfit” (“green nylon jacket, slacks, and muddied black athletic shoes”) and her mental health (“For Kotakis, strong emotions and felines go together like a cat and a lap.”) than he does the scientific papers he references (never mind those he overlooks).

His reference to “the feral feeding movement” reflects Smith’s fundamental misunderstanding of TNR, and his dogged efforts to steer the conversation away from sterilization, population control, reduced shelter killing, and the like—to focus on the alleged environmental consequences of subsidizing these “efficient bird killers and disease spreaders.”

Here, too, Smith misses the mark—failing to dig into the topic deeply enough to get beyond press releases, superficial observations, rhetorical questions, and his own bias.

Make no mistake: there’s an agenda here.

Science: The Usual Suspects

“Environmentalists,” writes Smith, “point out that outdoor cats are a greater problem to the natural ecological balance than most people realize.” Actually, what most people (including Smith, perhaps) don’t realize is that Smith’s sources can only rarely defend their dramatic claims with solid science.

Populations and Predation

Smith’s reference to the American Bird Conservancy, which, we’re told, “estimates that America’s 150 million outdoor cats kill 500 million birds a year,” brings to mind the 2010 L.A. Times story in which Steve Holmer, ABC’s Senior Policy Advisor, told the paper there were 160 million feral cats in the country.

Smith got a better answer out of ABC—but ABC’s better answers are only slightly closer to the truth.

Surveys indicate that about two-thirds of pet cats are kept indoors, which means about 31 million are allowed outside (though about half of those are outdoors for less than two or three hours a day). [1–3]. So where do the other 120 million “outdoor cats” come from? And if there are really 150 million of them in the U.S.—roughly one outdoor cat for every two humans—why don’t we see more of them?

Reasonable questions, but Smith is no more interested in asking than ABC is in answering.

The closest Smith comes to supporting ABC’s predation numbers is a reference to Jonathan Franzen’s latest novel, Freedom, a book “about a birder who declares war on ‘feline death squads’ and calls cats the ‘sociopaths of the pet world,’ responsible for killing millions of American songbirds.” (The fact that Franzen sits on ABC’s board of directors seems to have escaped Smith’s notice.)

In Smith’s defense, chasing down ABC’s predation numbers is a fool’s errand. Such figures—like the rest of ABC’s message regarding free-roaming cats—have more to do with marketing and politics than with science.

No 1. Killer?

For additional evidence, Smith turns to Pete Marra’s study of gray catbirds in and around Bethesda, MD.

“In urban and suburban areas, outdoor cats are the No. 1 killer of birds, by a long shot, according to a new study in the Journal of Ornithology. Researchers from the Smithsonian Institution put radio transmitters on young catbirds and found that 79 percent of deaths were caused by predators, nearly half of which were cats.”

Let’s see now… half of 79 percent… That’s nearly 40 percent of bird deaths caused by cats, right? Well, no.

Although SF Weekly included a link to the Ornithology article on its Website, it seems Smith never read the paper. Like so many others (e.g., The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor, etc.), he went with the story being served up by Pete Marra and the Smithsonian.

The real story, it turns out, is far less dramatic than headlines would suggest. In fact, neighborhood cats were observed killing just six birds.

What’s more, even if Marra and his colleagues are correct about the three additional kills they attribute to cats, the title of “No. 1 killer of birds” goes not to the cats, but to unidentified predators, as detailed in the Ornithology paper:

“During our study of post-fledging survival, 61% (42/69) of individuals died before reaching independence. Predation on juveniles accounted for 79% (33/42) of all mortalities (Bethesda 75% (6/8), Spring Park 75% (12/16), and Opal Daniels 83% (15/18) with the vast majority (70%) occurring in the first week post-fledging. Directly observed predation events involved domestic cats (n = 6; 18%), a black rat snake (n = 1; 3%), and a red-shouldered hawk (n = 1; 3%). Although not all mortalities could be clearly assigned, fledglings found with body damage or missing heads were considered symptomatic of cat kills (n = 3; 9%), those found cached underground of rat or chipmunk predation (n = 7; 21%) and those found in trees of avian predation (n = 1; 3%). The remaining mortalities (n = 14; 43%) could not be assigned to a specific predator. Mortality due to reasons other than predation (21%) included unknown cause (n = 2; 22%), weather related (n = 2; 22%), window strikes (n = 2; 22%) and individuals found close to the potential nest with no body damage (n = 3; 34%), suggesting premature fledging, disease or starvation.” [4]

Taken together, the detailed mortality figures and the study’s small sample size make a mockery of Smith’s claim, and—more important—its implications for feral cat management. Which might explain why he didn’t bother to share this information with readers.

The Power of One

“If trappers miss a single cat,” warns Smith, “populations can rebound if they’re continuously fed, because a fertile female can produce 100 kittens in her lifetime. Miss too many, and the practice of leaving cat food in wild areas will actually increase their numbers by helping them to survive in the wild.”

As Michael Hutchins, Travis Longcore, and others have pointed out, I don’t have a degree in biology. Still, I don’t think I’m going out on a limb when I say that “a single cat” isn’t likely to reproduce on its own.

Nor is a female cat—even with help—going to produce 100 kittens over the course of her lifetime. A study of “71 sexually intact female cats in nine managed feral cat colonies” found that:

“Cats produced a mean of 1.4 litters/y, with a median of 3 kittens/litter (range, 1 to 6). Overall, 127 of 169 (75%) kittens died or disappeared before 6 months of age. Trauma was the most common cause of death.” [5]

To produce 100 kittens, then, an unsterilized female would have to live at least 25 years. Smith fails to reconcile—or even acknowledge—the obvious discrepancy between claims of of-the-charts fecundity and—to use David Jessup’s phrase—the “short, brutal lives” [6] of feral cats.

Do these cats breed well into their golden years, or, are they “sickened by bad weather, run over by cars, killed by coyotes, or simply starved because feeders weren’t able to attend to a cat colony for the several years or more that are called for,” as Smith suggests?

Clearly, the two scenarios are mutually exclusive.

California Quail

The closest we get to the “demise of native birds” promised on the cover is Smith’s observation that “wildlife advocates blame the city’s forgiving attitude toward feral cats for helping to almost wipe out native quail, which used to be commonplace.”

This is not a new complaint, as a 1992 story in the San Francisco Chronicle illustrates:

“A decade ago, the hedges and thickets of Golden Gate Park teemed with native songbirds and California Valley quail. Now the park is generally empty of avian life, save for naturalized species such as pigeons, English sparrows and starlings.” [7]

But the Chronicle, despite its dire proclamation (“One thing seems certain: San Francisco can have a healthy songbird population or lots of feral cats, but not both.” [7]), did no better than SF Weekly at demonstrating anything more than correlation. This, despite interviews with scientists from the California Academy of Sciences, Point Reyes Bird Observatory, and Golden Gate Chapter of the Audubon Society.

A few years later, Cole Hawkins thought he found the answer. Conducting his PhD work at Lake Chabot Regional Park, Hawkins reported that where there were cats, there were no California Quail—the result, he argued, “of the cat’s predatory behavior.” [8] In fact, Hawkins found very little evidence of predation, and failed to explain why the majority of ground-nesting birds in his study were indifferent to the presence of cats—thus undermining his own dramatic conclusions.

A quick look at A. Starker Leopold’s 1977 book The California Quail (a classic, it would seem, given how often it’s cited) offers some interesting insights on the subject. (Full disclosure: this was a quick look—I turned immediately to the glossary, and then to the two sections corresponding to “Predators, cats and dogs.”)

In the “Quail Mortality” chapter, Leopold describes Cooper’s Hawk as “the most efficient and persistent predator of California Quail,” [9] in stark contrast to cats.

“The house cat harasses quail and may drive them from the vicinity of a yard or a feeding station (Sangler, 1931), but there is little evidence that they catch many quail in wild situations. Hubbs (1951) analyzed the stomach contents of 219 feral cats taken in the Sacramento Valley and recorded one California Quail. Feral cats, like bobcats, prey mostly on rodents.” [9, emphasis mine]

The picture changes somewhat, though, when we get to Leopold’s chapter on “Backyard Quail”:

“Cats… not only molest quail, but skillful individuals capture them frequently… Feline pets that are fed regularly are not dependent on catching birds for a living, but rather they hunt for pleasure and avocation. They can afford to spend many happy hours stalking quail and other birds around the yard, and hence they are much more dangerous predators than truly feral cats that must hunt for a living and therefore seek small mammals almost exclusively (wild-living cats rarely catch birds).” [9]

As to how many “skillful individuals” reside in Golden Gate Park, it’s anybody’s guess. (The idea that few cats catch many birds while many cats catch few if any, however, is well supported in the literature.) And, while they may be well fed, it’s not clear that their very public “yard” and skittish nature afford the park’s cats “many happy hours stalking.”

(A more recent source, The Birds of North America, provides an extensive list of California Quail predators—including several raptor species, coyotes, ground squirrels, and rattlesnakes. Cats are mentioned only as minor players. [10])

Toxoplasmosis

Another complaint from the area’s wildlife advocates, writes Smith, is “Toxoplasma gondii, “shed in cat feces, that threatens endangered sea otters and other marine mammals.” But not all T. gondii is the same. In fact, nearly three-quarters of the sea otters examined as part of one well-known study [11] were infected with a strain of T. gondii that hasn’t been traced to domestic cats. [12]

Once again, domestic cats have become an easy target—but, as with their alleged impact on California Quail, there’s plenty we simply don’t know.

Feral Feeding

For Smith, the trouble with TNR is its long-term maintenance of outdoor cat populations. “Its years of regular feeding,” he argues, citing Travis Longcore’s selective review of the TNR literature, [13] (which Smith mischaracterizes as “a study”), “causes ‘hyperpredation,’ in which well-fed cats continue to prey on bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian populations, even after these animals become so scarce they can no longer sustain natural predators.”

But that’s not what happened in Hawkins’ study (though he did his best to suggest as much). And it’s not what happened in the two Florida parks Castillo and Clarke used to study the impact of TNR.

Over the course of approximately 300 hours of observation (this, in addition to “several months identifying, describing, and photographing each of the cats living in the colonies” [14] prior to beginning their research), the researchers “saw cats kill a juvenile common yellowthroat and a blue jay. Cats also caught and ate green anoles, bark anoles, and brown anoles. In addition, we found the carcasses of a gray catbird and a juvenile opossum in the feeding area.” [14]

That’s it—from nearly 100 cats (about 26 at one site, and 65 at another).

Calhoon and Haspel, too, found little predation among the free-roaming cats they studied in Brooklyn: “Although birds and small rodents are plentiful in the study area, only once in more than 180 [hours] of observations did we observe predation.” [15]

Feeding and Population Control

Smith’s description of the vacuum effect reflects his misunderstanding of the phenomenon and the role feeding play in TNR more broadly:

“Feral cat advocates believe removing cats from the wild creates a natural phenomenon known as the ‘vacuum effect,’ in which new cats will replace absent ones. (Key to the ‘vacuum’ are the tons of cat food TNR supporters place twice a day, every day, at secret feeding stations nationwide.)”

Smith would have readers believe that TNR practitioners bait cats the way hunters bait deer. In fact, the food comes after the cat(s), not the other way around.

Cats are remarkably resourceful; where there are humans, there is generally food and shelter to be found. Indeed, even where no such support is provided, cats persist. On Marion Island—barren, uninhabited, and only 115 square miles in total area—it took 19 years to eradicate about 2,200 cats, using disease (feline distemper), poisoning, intensive hunting and trapping, and dogs. [16, 17]

As Bester et al. observe, the island’s cats didn’t require “tons of cat food” as an incentive to move into “vacuums”:

“The recolonization of preferred habitats, cleared of cats, from neighbouring suboptimal areas served to continually concentrate surviving cats in smaller areas.” [16]

Still, those “tons of cat food TNR supporters place twice a day, every day, at secret feeding stations nationwide” are key to the success of TNR—just not in the way Smith suggested. Feeding allows caretakers to monitor the cats in their care, “enrolling” new arrivals as soon as possible.

By bringing these cats out into the open—via managed colonies—they’re much more likely to be sterilized and, in some cases, vaccinated. Many will also find their way into permanent homes. Take away the food, and these cats will merely slip back into the surroundings, go “underground.”

And in no time at all, the ones that weren’t sterilized will be breeding.

• • •

By framing TNR (the “feral feeding movement,” as he insists on calling it) as “animal welfare ethics on one side, and classic environmental ethics on the other,” Smith overlooks some critical common ground: all parties are interested in reducing the population of feral cats. He also allows himself to give in to an easy—and rather tired—narrative: the crazy cat ladies v. the respected scientists.

At the same time Smith recognizes Kotakis’ dedication and accomplishment (“In her tiny bit of territory in the eastern parts of the park, her method and dedication might just have created a tipping point that has produced a humane ideal of fewer feral cats.”), he can’t resist commenting on her OCD (including a quote from a clinical psychologist who, we can safely assume, has never even met Kotakis).

Meanwhile, Smith couldn’t care less about looking into the science.

I suppose “Live and Let Kill” is balanced in the sense that Smith gives “equal time” to both sides of the issue, but that’s not good enough. Serious journalism demands that readers are provided the truest account possible.

Literature Cited

1. APPA, 2009–2010 APPA National Pet Owners Survey. 2009, American Pet Products Association: Greenwich, CT. http://www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp

2. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.1541

3. Lord, L.K., “Attitudes toward and perceptions of free-roaming cats among individuals living in Ohio.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2008. 232(8): p. 1159-1167. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_232_8_1159.pdf

4. Balogh, A., Ryder, T., and Marra, P., “Population demography of Gray Catbirds in the suburban matrix: sources, sinks and domestic cats.” Journal of Ornithology. 2011: p. 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0648-7

http://nationalzoo.si.edu/scbi/migratorybirds/science_article/pdfs/55.pdf

5. Nutter, F.B., Levine, J.F., and Stoskopf, M.K., “Reproductive capacity of free-roaming domestic cats and kitten survival rate.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1399–1402. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1399

6. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552312

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1377.pdf

7. Martin, G. (1992, January 13). Feral Cats Blamed for Decline In Golden Gate Park Songbirds. The San Francisco Chronicle, p. A1,

8. Hawkins, C.C., Impact of a subsidized exotic predator on native biota: Effect of house cats (Felis catus) on California birds and rodents. 1998, Texas A&M University

9. Leopold, A.S., The California Quail. 1977, Berkeley: University of California Press.

10. Calkins, J.D., Hagelin, J.C., and Lott, D.F., California quail. The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century. 1999, Philadelphia, PA: Birds of North America, Inc. 1–32.

11. Conrad, P.A., et al., “Transmission of Toxoplasma: Clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels of Toxoplasma gondii flow into the marine environment.” International Journal for Parasitology. 2005. 35(11-12): p. 1155-1168. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4GWC8KV-2/2/2845abdbb0fd82c37b952f18ce9d0a5f

12. Miller, M.A., et al., “Type X Toxoplasma gondii in a wild mussel and terrestrial carnivores from coastal California: New linkages between terrestrial mammals, runoff and toxoplasmosis of sea otters.” International Journal for Parasitology. 2008. 38(11): p. 1319-1328. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4RXJYTT-2/2/32d387fa3048882d7bd91083e7566117

13. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap-Neuter-Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894. http://www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/pdf/Management_claims_feral_cats.pdf

14. Castillo, D. and Clarke, A.L., “Trap/Neuter/Release Methods Ineffective in Controlling Domestic Cat “Colonies” on Public Lands.” Natural Areas Journal. 2003. 23: p. 247–253.

15. Calhoon, R.E. and Haspel, C., “Urban Cat Populations Compared by Season, Subhabitat and Supplemental Feeding.” Journal of Animal Ecology. 1989. 58(1): p. 321–328. http://www.jstor.org/pss/5003

16. Bester, M.N., et al., “A review of the successful eradication of feral cats from sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Southern Indian Ocean.” South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 2002. 32(1): p. 65–73.

http://www.ceru.up.ac.za/downloads/A_review_successful_eradication_feralcats.pdf

17. Bloomer, J.P. and Bester, M.N., “Control of feral cats on sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Indian Ocean.” Biological Conservation. 1992. 60(3): p. 211-219. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V5X-48XKBM6-T0/2/06492dd3a022e4a4f9e437a943dd1d8b