U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under fire for proposed roundups of free-roaming cats in the Florida Keys, an out-of-control burn on National Key Deer Refuge land, and participation in anti-TNR workshop.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under fire for proposed roundups of free-roaming cats in the Florida Keys, an out-of-control burn on National Key Deer Refuge land, and participation in anti-TNR workshop.

Many U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel are, I suspect, looking forward to October—or at least putting September behind them. For those involved with USFWS’s “war on cats,” this month’s been a tough one: too much of the wrong kind of attention.

Camera (en)Trap(ment) Project

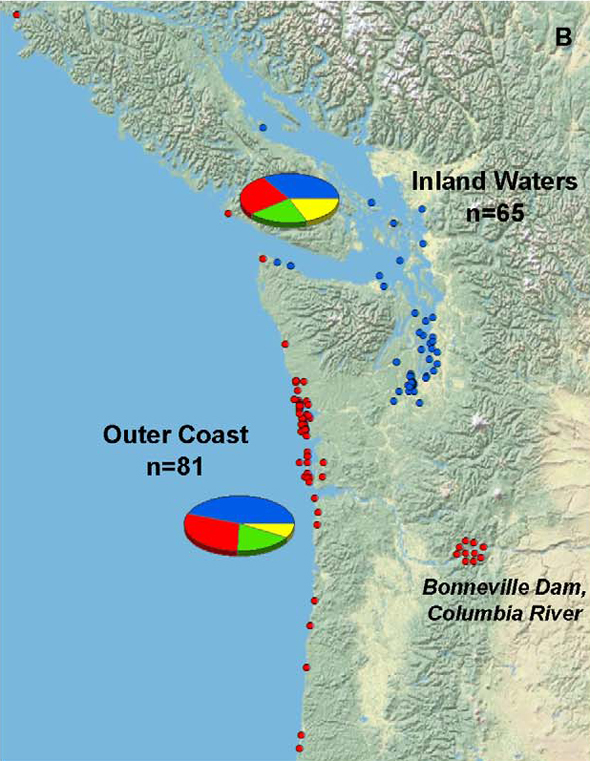

September got off to a rocky start with readers (myself included) responding to news of camera traps being used in Florida’s National Key Deer Refuge “to document the number of cats stalking prey in the refuge.”

According to Key West Citizen reporter Timothy O’Hara, cats appeared on 5 percent of the “nearly 7,000 [photos] snapped so far,” whereas the endangered Lower Keys Marsh Rabbit appeared on just 3 percent. (Deer and raccoons topped the list, though specific percentages weren’t mentioned.)

Future plans include “a more in-depth study to get a better handle on the number of cats,” which, says USFWS biologist Chad Anderson, who was interviewed for the story, “will give us better insight into the predator management plan [of which I’ve been highly critical]. We want it to be as effective and efficient as possible.”

Five days later, Big Pine Key resident Jerry Dykhuisen took USFWS to task in a letter to the editor calling O’Hara’s article “our quarterly puff piece about how great it’s all going to be when feral cats are trapped and removed from Big Pine Key.” Dykhuisen, vice president of Forgotten Felines, pointed out the incredible expense associated with the proposed roundup (a “government boondoggle that is nothing more than a waste of our tax dollars and job security for U.S. Fish and Wildlife”) and the risk of skyrocketing rodent populations if eradication efforts were actually “successful,” and challenges the “‘best available science’ of which they are so proud” (which “is not really very good science at all, being decades old, using statistical methods that are highly suspect, and not even being conducted on Big Pine.”).

“Tax dollars are at a premium in this economy,” wrote Dykhuisen, “and the idea of spending more than $10,000 per cat on a project that has no chance of success is mindless government at its worst.”

The following week, a letter to the editor from Forgotten Felines volunteer Valerie Eikenberg called the camera trap project “a lame-brain experiment,” criticizing Refuge personnel for baiting the cameras with cat food. “Why spend thousands of taxpayer dollars to figure out a question that any second-grader could answer,” she asked.

Refuge Manager Anne Morkill disputes Eikenberg’s claim: “extremely small amounts of bait were used at only two camera trap sites located at unauthorized cat feeding stations, where the cats were already lured by food. The purpose was to get the animals to stop and pause for a clear photo for identification purposes.” (I received a similar explanation by e-mail from Anderson.)

Note: I’ve tried to contact O’Hara, who badly misrepresented the science in his story (for example: “Research indicates that cat predation accounts for 50 percent to 77 percent of the deaths of Lower Keys marsh rabbits and Key Largo woodrats.”), but he’s not responded to my e-mail requests.

(Mis)prescribed Burn

Just two weeks later, Refuge personnel once again found themselves defending their actions, this time for a prescribed burn that grew quickly out of control, scorching about 100 acres—five times what was originally planned.

For some, at least, this was the last straw. “Morkill has to go!” read one particularly harsh comment to a Key West Citizen story about the fire.

“Not tomorrow, not next week, not at the end of the fiscal year, NOW!! She is completely over her head and needs to transfer somewhere else. From the complete mishandling of the feral cat situation [to] the out of controlled prescribed burn that threatened both residents AND sensitive wildlife… Ms. Morkill is a complete and total failure at her position. What a travesty. Go back to wherever you came from Anne, you’re a failed experiment in the Keys.”

Earlier this week, USFWS officials met with residents to explain the results of an internal investigation into the fire.

According to USFWS Fire Ecologist Vince Carver, “The review team came up with three findings: One, it was too dry to burn. Two, the [fire] crew that did it, the majority of them did not have enough experience for this type of burn. And three, after they did screw up, they did a fantastic job.” [1]

Refuge fire management specialist Dana Cohen “repeatedly apologized to residents, saying, ‘We made a bad call’ in deciding to burn, but most appeared unmoved.” [1] The “unhappy audience,” as Citizen reporter Adam Linhardt describes them, were short on patience, “speaking out and lambasting” USFWS officials. “One person described the burn as a ‘fiasco’ and called for Cohen’s firing.” [1]

National Feral Cat Policy

A day after the blaze on Big Pine Key, USFWS was trying to tamp down another fire of its own making. This one, too, had gotten out of hand—but on a national scale.

In a post on its Open Spaces blog, USFWS responded to “many expressions of interest and concern regarding participation by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employees at an upcoming Wildlife Society conference.” This, of course, is a reference to Informing Local Scale Feral Cat Trap-Neuter-Release Decisions, the day-long workshop being presented by Tom Will, Mike Green (both of USFWS), and Christopher Lepczyk (University of Hawaii).

As part of that conference, two Service biologists are presenting a workshop designed to help wildlife biologists and other conservationists effectively communicate the best available science on the effects on wildlife from free-ranging domestic cats. The Service has no national policy concerning trap-neuter-release programs or feral cats.

If there’s no official policy, it’s not for lack of effort.

In his 2010 presentation to the Bird Conservation Alliance, What Can Federal Agencies Do? Policy Options to Address Cat Impacts to Birds and Their Habitats, Will is pushing for a “Firm policy statement—clear, definitive, easily available—as a tool for partners.” In fact, it looks like he’s suggesting that such a policy already exists, citing, for example, a 2007 “response to inquiry” from the USFWS Charleston Field Office:

Is it still FWS policy to promote legislation banning feeding of wildlife? Yes. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) stands firmly behind its recommendations promoting legislation banning the feeding of wildlife, especially nuisance species such as feral cats. Local governments are better equipped than are Federal and State agencies to regulate feral and free-ranging cats since most local governments have ordinances in place to address domestic animal issues as well as animal control services and personnel to implement those ordinances.

Is it still FWS policy opposing free ranging cats and establishment of feral cat colonies? Yes. The Service continues to oppose the establishment of feral cat colonies as well as the perpetuation and continued operation of feral cat colonies. As an agency responsible for administering the regulatory provisions of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), the Service’s position is that those practicing Trap-Neuter-Release (TNR) could be subject to prosecution under those laws.

Is it still FWS policy opposing TNR programs? Yes… the Service’s New Jersey Field Office correctly states that “a municipality that carries out, authorizes, or encourages others to engage in an activity that is likely to result in take of federally protected species, such as the establishment or maintenance of a managed TNR cat colony, may be held responsible for violations of Section 9 of the ESA.”

Will goes on to cite several more passages from the letter quoted above, sent in November 2009 from the New Jersey Field Office to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Division of Fish and Wildlife “in support of the New Jersey Fish and Game Council’s Resolution on Trap-Neuter-Release (TNR) and free-ranging domestic cats, passed June 19, 2007.”

The Service strongly opposes domestic or feral cats (Felis catus) being allowed to roam freely within the U.S. due to the adverse impacts of these non-native predators on federally listed threatened and endangered (T&E) species, migratory birds, and other vulnerable native wildlife. Therefore, the Service opposes TNR programs that allow return of domestic or feral cats to free-ranging conditions.

Migratory birds are Federal trust resources and are afforded protection under the MBTA, which prohibits the take of a migratory bird’s parts, nest, or eggs. Many species of migratory birds, wading birds, and songbirds nest or migrate throughout New Jersey. Migratory birds could be subject to predation from State municipality, or land manager-authorized cat colonies and free-ranging feral or pet cats. Predation on migratory birds by cats is likely to cause destruction of nests or eggs, or death or injury to migratory birds or their young, thereby resulting in a violation of the MBTA.

All of which looks a lot like a “national policy concerning trap-neuter-release programs or feral cats.” Which might explain why the American Bird Conservancy has the NJ Field Office letter posted on its website (PDF). (ABC and TWS were among the signatories to a letter sent earlier this year to Department of Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, “urg[ing] the development of a Department-wide policy opposing Trap-Neuter-Release and the outdoor feeding of cats as a feral cat management option, coupled with a plan of action to address existing infestations affecting lands managed by the Department of the Interior.”)

To hear USFWS tell it, Will and Green don’t even speak for USFWS.

In order to protect the independence and integrity of their work and the quality of the scientific information generated, the Service does not review or edit their work based on its potential policy implications. Any findings or conclusions presented at this workshop, as well as other scientific papers and presentations by Service employees, are those of the organizers and do not necessarily represent those of the Fish and Wildlife Service.

How exactly does that work? Are taxpayers (who are, like it or not, supporting TWS’s conference: “the Service is a sponsor of the conference as a whole”) expected to believe that Informing Local Scale Feral Cat Trap-Neuter-Release Decisions wasn’t put together “on company time,” using agency resources? Like me, commenter “Mrs. McKenna” isn’t buying it:

“I find it very strange that there would be not be an edit or review of the presentations done by employees/consultants (personnel on your payroll.) Quite frankly, I know of no organization that would allow taxpayer paid employees to present at a conference of this magnitude without a screening of materials to be presented. In fact, one could deem this type of policy quite irresponsible… If there were no interest in presenting a specific viewpoint supported by U.S. Fish & Wildlife for current or upcoming policies, one can be quite certain no such presentation would be sponsored.”

Mrs. McKenna and I are, it turns out, not the only skeptics. At last check, there were 50 comments on the USFWS post (not all of them critical of the Service, of course), a record for the Open Space blog (which, since its inception in late April, has attracted just 140 comments across 97 posts—including the August 2 post about “a recent incident where the Service inadvertently issued a citation in Fredericksburg, Virginia,” which attracted 46 comments).

Uncommitted

Although USFWS is, according to its Office of External Affairs, “committed to using sound science in its decision-making and to providing the American public with information of the highest quality possible,” recent events suggest otherwise.

Actually, past events tell a similar story.

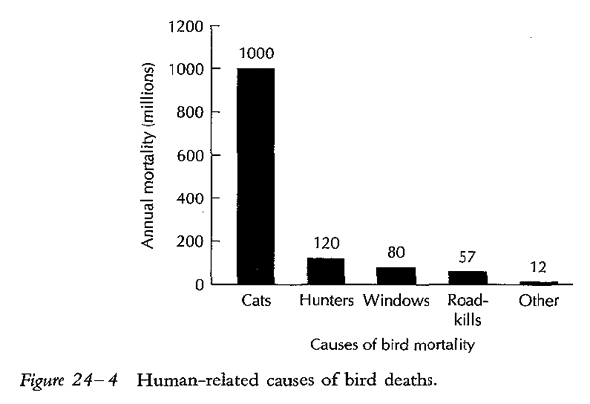

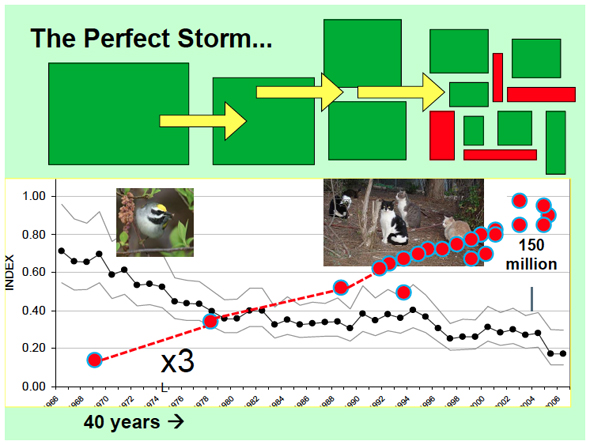

In its Migratory Bird Mortality fact sheet (PDF), published in January 2002, USFWS offers this prediction: “Many citizens would be surprised to learn that domestic and feral cats may kill hundreds of millions of songbirds and other avian species each year.”

“A recent study in Wisconsin estimated that in that state alone, domestic rural cats kill roughly 39 million birds annually. Add the deaths caused by feral cats, or domestic cats in urban and suburban areas, and this mortality figure would be much higher.” [2]

In this case, the Service’s “best available science” can be traced to the infamous Wisconsin Study, [3] and—eventually—to “a single free-ranging Siamese cat” that frequented a rural residential property in New Kent County, Virginia. [4])

Nearly 10 later, Migratory Bird Mortality is still available from the USFWS website. So much for “using sound science in its decision-making and to providing the American public with information of the highest quality possible.”

USFWS is right about one thing, though: many citizens are surprised—just not in the way the Service imagined. The public, to whom USFWS is ostensibly accountable, is surprised at the way their tax dollars are being used to fund a witch-hunt. And, judging by the overwhelming response to the USFWS/TWS workshop (see, for example, Best Friends Animal Society’s Action Alert, blog posts from Alley Cat Rescue and BFAS co-founder Francis Battista, and the Care2 petition), the public has had enough.

With access to both information and “broadcast” technology more accessible than ever, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for USFWS to continue with business as usual. The people the Service is supposed to—well, serve—are demanding better science, more transparency, and greater accountability. People are paying attention like never before.

Think of it as “the new normal.”

Literature Cited

1. Linhardt, A. (2011, September 29). Residents rage about rogue fire—Fed officials apologize: ‘We made a bad call’. The Key West Citizen, p. 1A,

2. n.a., Migratory Bird Mortality. 2002, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Arlington, VA. www.fws.gov/birds/mortality-fact-sheet.pdf

3. Coleman, J.S., Temple, S.A., and Craven, S.R., “Cats and Wildlife: A Conservation Dilemma.” 1997. http://forestandwildlifeecology.wisc.edu/wl_extension/catfly3.htm

4. Mitchell, J.C. and Beck, R.A., “Free-Ranging Domestic Cat Predation on Native Vertebrates in Rural and Urban Virginia.” Virginia Journal of Science. 1992. 43(1B): p. 197–207. www.vacadsci.org/vjsArchives/v43/43-1B/43-197.pdf

North American Opossum with winter coat. Photo courtesy of

North American Opossum with winter coat. Photo courtesy of