Promoting the Culture of Killing can’t be easy, what with public opinion strongly opposed to the lethal roundups of community cats [1, 2] and, more generally, the use of lethal methods as a shelter’s means of population control. [3] Nevertheless, there are those who persist.

Witness, for example, Travis Longcore’s comment on the Vox Felina Facebook page, left in response to my April 14th blog post, in which I argued that the injunction prohibiting the City of Los Angeles from supporting TNR—the result of a lawsuit in which Longcore’s Urban Wildlands Group was lead petitioner—is increasing the risks to the very wildlife and environment he claims to protect.

Longcore’s bar chart and references to statistics, extrapolation, and property rights were, I can only assume, intended to give the impression of a well-reasoned, comprehensive rejoinder. It was, in fact, nothing of the sort. Indeed, even a cursory examination suggests that Longcore’s reasoning is no better than his arithmetic.

Reduced Intake Numbers, Part 1

Not surprisingly, Longcore, who serves as both science director for the Urban Wildlands Group and Los Angeles Audubon’s president, argues that “the injunction is a huge success.”

“By the Department of Animal Services’ own statistics, the number of cats taken in has gone down each year since the injunction went into effect… Given that the number of cats going in to L.A. shelters is as low as it has ever been, what are you complaining about?”

There’s plenty to complain about, actually, even if we set aside all the dead cats and kittens.

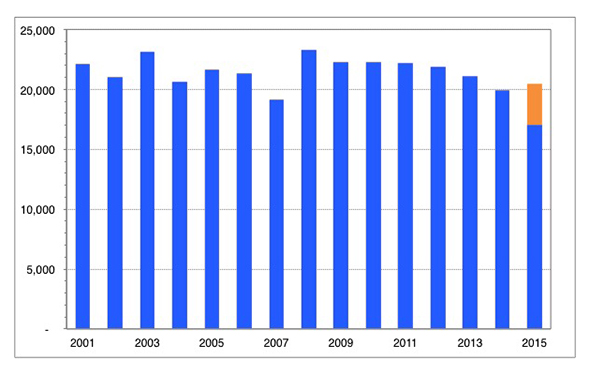

Let’s start with Longcore’s extrapolation. It’s not clear how Longcore arrived at his estimate of approximately 17,000 cat/kitten intakes for 2014–15, but it might have something to do with that reference to nine months of data reported. In fact, only eight months of data have been reported: July 2014 through February 2015 (just as Longcore noted). And, based on these data, intake of cats and kittens are on track to increase 2.8 percent, not fall 14.7 percent, as Longcore suggests.

Cat/kitten intake data, 2000–01 through 2014-15. For 2014–15, blue bar is Longcore’s estimate; orange bar is corrected estimate. Source: L.A. Animal Services.

Another possible contributing factor: the seasonal variation in intake of cats and, more to the point, kittens. Indeed, examining data from the past few years, it’s clear that March–June intakes make up 39–41 percent of L.A. Animal Services’ yearly total. In other words, it seems Longcore failed to account for “kitten season.”

Granted, we all make math blunders. Still, Longcore’s erroneous estimate, if correct, would represent the lowest cat and kitten intake in at least 15 years. Surely, such a dramatic reduction warrants a second look—especially when it’s being used in an attempt to shape sheltering policy for all of Los Angeles.

One would expect some sort of explanation, too. Are we really expected to believe the significant drop-off in intakes is the result of the injunction prohibiting the City of Los Angeles from supporting TNR?

How would that even make sense?

In doesn’t, of course. But more on that shortly.

Publicly Funded Killing

“The injunction did not stop privately funded TNR in Los Angeles,” Longcore continues.

“It did, however, preserve the right of people to trap feral cats and take them to the shelter, which is an essential check that keeps feral cat numbers and feral cat feeders in control.”

So residents bringing cats to L.A.A.S. to be killed keep feral cat numbers “in control”? Just last year, in a letter to California Assembly Member Katcho Achadjian, Chair of the Committee on Local Government, opposing AB-2343, Longcore argued (using L.A.A.S. data through 2012) that “policies put in place after the Hayden Act [1999] have resulted in an increase in the percentage of cats taken in to shelters that are deemed to be feral, suggesting that the stray/feral cat problem has become worse” (emphasis mine).

So the “problem” has become worse, despite all those residents keeping the “feral” cats in check—and the “hugely successful” injunction (issued in January 2010)?

Longcore’s story simply doesn’t hang together.

Now, it’s true that privately funded TNR has increased since 2010—responsible, at least in part, for an 11 percent decrease in the intake of unweaned kittens last year, as compared to 2010–11.* But under the provisions of the injunction, L.A.A.S. staff are not even permitted to refer residents to the organizations doing the TNR. As L.A. Weekly reporter Hayley Fox pointed out, “TNR doesn’t stand much chance of success until the city joins the effort.” [4]

In any case, why is Longcore so opposed to the use of public funding for TNR efforts but (apparently) OK with its use for killing—an ineffective approach with no end in sight? Of course this is hardly usual among TNR opponents—but, again, it’s definitely out of step with public opinion.

The Source of “Unwanted Animals”

“The injunction furthermore did not take away spay/neuter resources,” Longcore explains. “The coupons are available for owned pets, which is where those funds do the most good for reducing the total number of unwanted animals.”

Although it’s true that vouchers are available for qualified pet owners, there’s no reason to think that such programs “do the most good for reducing the total number of unwanted animals” in Los Angeles or anywhere else. In fact, according to the American Pet Product Association’s 2013–14 National Pet Owners Survey, 91 percent of pet cats are sterilized. [5]

Naturally, we would all like to close that nine-point gap, but nobody familiar with the topic would seriously suggest that such efforts offer the best return on investment if the objective is to reduce the population of community cats.

Reduced Intake Numbers, Part 2

“Your preferred scenario,” concludes Longcore, “which apparently is to refuse to allow cats to be taken to shelters, would in fact result in a massive increase in the number of outdoor cats.”

Fair enough—this is my preferred scenario, largely because return-to-field programs have demonstrated dramatic reductions in shelter killing. [6, 7] But wait. Didn’t Longcore begin by suggesting (incorrectly, it turns out) that shelter intakes were down considerably—and that this was evidence of the injunction’s success? But now, lower intakes lead to “a massive increase in the number of outdoor cats”?

It seems he wants to have it both ways.

Then again, that was sort of my original point: Longcore simply can’t continue impeding TNR efforts and claim he’s protecting wildlife. As I wrote in my letter to L.A. Weekly, his position is at odds with the relevant science, public opinion, and common sense.

And more than five years after the injunction was imposed, I don’t imagine I’m the only one who’s noticed.

* While we’re on the subject, Longcore’s response misrepresents rather significantly what I wrote. I argued that “the number [of newborn kittens] entering the shelter system”—not the overall intake number—“is a reasonable marker of the larger population trend.”

Literature Cited

1. Chu, K. and W.M. Anderson, Law & Policy Brief: U.S. Public Opinion on Humane Treatment of Stray Cats, 2007, Alley Cat Allies: Bethesda, MD.

2. Wolf, P.J. New Survey Reveals Widespread Support for Trap-Neuter-Return. Humane Thinking, 2015. http://spot.humaneresearch.org/content/new-survey-reveals-widespread-support-trap-neuter-return

3. Karpusiewicz, R. AP-Petside.com Poll: Americans Favor No-Kill Animal Shelters. 2012. http://www.petside.com/article/ap-petsidecom-poll-americans-favor-no-kill-animal-shelters

4. Fox, H., Cat Fight, in L.A. Weekly2015.

5. APPA, 2013–2014 APPA National Pet Owners Survey, 2014, Americna Pet Products Association.

6. Levy, J.K., N.M. Isaza, and K.C. Scott, Effect of high-impact targeted trap-neuter-return and adoption of community cats on cat intake to a shelter. The Veterinary Journal, 2014. 201(3): p. 269–274. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1090023314001841

7. Johnson, K.L. and J. Cicirelli, Study of the effect on shelter cat intakes and euthanasia from a shelter neuter return project of 10,080 cats from March 2010 to June 2014. PeerJ, 2014. 2: p. e646. http://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.646

As always Peter, nailed it!!!!

I want to preface my comments by saying that Los Angeles Audubon Society does a lot of great work, which I have seen first hand as a volunteer. Surveys of Snowy Plovers, school visits to the Ballona Wetlands, habitat restoration in the Baldwin Hills, and other programs really make a huge difference in a city and region that is not well known for conservation of our natural resources. I’ll also say that Travis Longcore himself has contributed to the conservation discussion with research and policy recommendations that have challenged the PR narratives behind some questionable proposals in how to deal with our natural resources.

That said, I have always felt that the injunction against city involvement with TNR was counterproductive to the cause of protecting birds from predation by outdoor cats. As I have noted before, it was the city that referred me to a local TNR organization which helped me and my wife reduce a roughly 20 cat neighborhood “colony” down to a single outdoor cat. For too many reasons to get into here, taking the cats to be euthanized was not a viable option for us. So had the city provided us with only that single option, we would have instead opted for the approach that both cat and bird advocates should fear most, doing nothing.

I believe that both bird advocates and cat advocates can do a better job of changing this discussion from an “us versus them” discussion to one in which the pros and cons of different approaches are weighed and analyzed. There are no magic bullets, but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be thoughtfully discussing whether current feeding practices could be improved for the benefit of both cats and wildlife, or whether greater program accountability shouldn’t be implemented in some fashion.

I think that for the discussion to change, it is incumbent on wildlife advocates and cat advocates to separate the science of feral cat management from the ideology of feral cat management (fully understanding that cat advocates don’t typically employ a utilitarian model the way wildlife advocates do). I have been very surprised to see so many professional scientists defend what they admit are poorly constructed research papers (including one with a basic multiplication error) because the conclusions of those papers were ideologically desirable to them. A key principle of bird watching is that you use the field marks, behavior and other aspects of a bird to make an identification. In the case of feral cats, I think many bird watchers and wildlife enthusiasts are missing the field marks in favor of seeing what they want to see.

Walter Lamb

I agree, Kathleen, that the injunction is a significant impediment. It’s not clear what the next step(s) will be.