Below is a letter I wrote in response to a recent L.A. Weekly story. Unfortunately—especially since I learned this only after compiling and submitting my comments—the paper doesn’t seem to publish any letters, despite providing an online form for precisely this purpose.

Seems a shame to let it go to waste…

• • •

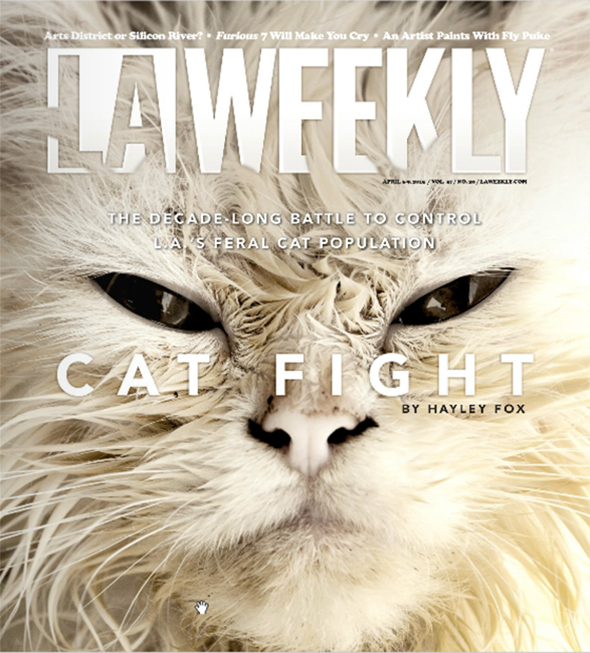

Hayley Fox’s recent story about Los Angeles’ unowned, free-roaming cats and the people who care for them (“Cat Fight,” March 31) made an important connection: the current injunction prohibiting the City of Los Angeles from supporting trap-neuter-return (TNR) efforts is, without a doubt, contributing to the deaths of thousands of newborn kittens annually. And since the number entering the shelter system—surely just a fraction of those being born to “community” cats—is a reasonable marker of the larger population trend, it’s clear that the injunction has backfired.

Indeed, the current policy, the result of a lawsuit brought by the Urban Wildlands Group (“dedicated to the protection of species, habitats, and ecological processes in urban and urbanizing areas,” according to the organization’s website), is doing more to drive up the population of community cats than any “army of cat lovers” is doing by providing them with handouts.

Let that sink in for a minute.

Travis Longcore, the Urban Wildlands Group’s science director and Los Angeles Audubon’s president, is at best misguided when he frames the issue as either cats or wildlife. TNR is, in the vast majority of instances, a benefit to cats and wildlife alike. Indeed, the science is quite clear: there are only two approaches known to reduce the population of community cats: (1) intensive TNR efforts or (2) intensive eradication efforts, such as those using poison, disease, lethal trapping, and hunting on small oceanic islands.

Obviously, given the horrendous methods employed (and astronomical expense), this option is unlikely to attract much support in Los Angeles (or anywhere else in the U.S.). The only feasible option, then, is TNR. Arguments about the limitations of its effectiveness, the impact of outdoor cats on wildlife and the environment, and so forth, are largely missing the point. In the vast majority of instances, TNR is simply the best option available.

Nobody even remotely familiar with the issue would suggest that the “traditional” approach (i.e., complaint-driven impoundment typically resulting in death) is stabilizing or reducing the population of community cats. And yet, this is precisely what Longcore is implying with his unwavering opposition to TNR. It’s a position at odds with the relevant science, public opinion, and common sense.

While it seems Longcore is unmoved by the deaths of thousands of cats and kittens (with no end is sight, and at taxpayer expense), one might imagine that he would see—finally, more than five years after the injunction—that the policy he helped to shape is increasing the risks to the very wildlife and environment he claims to protect.