According to last Friday’s USA Today, “Health officials have confirmed that an Oregon man has the plague after he was bitten while trying to take a dead rodent from the mouth of a stray cat.”

“State public health veterinarian Dr. Emilio DeBess said the man was infected when he was bitten by the stray his family befriended. The cat died and its body is being sent to the CDC for testing.”

Other news reports suggest that the source of the bacteria—which might have been the rodent—remains uncertain. (Indeed, the fact that the cat’s body was submitted for testing suggests, that there is some question about this. The cat’s death—also unexplained—raises additional questions.)

“Humans usually get plague,” explains the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on its website, “after being bitten by a rodent flea that is carrying the plague bacterium or by handling an animal infected with plague.”

“Between 1900 and 2010, 999 confirmed or probable human plague cases occurred in the United States… In recent decades, an average of seven human plague cases are reported each year (range: 1–17 cases per year).”

While the story has made headlines as far away as New Zealand, it’s gotten surprisingly little play among TNR opponents. The American Bird Conservancy and The Wildlife Society, in particular, rarely pass up such opportunities to rekindle their ongoing witch-hunt against free-roaming cats.

It’s still early, of course.

The Plague and the Witch-hunt

ABC’s 2004 brochure The Great Outdoors is No Place for Cats (PDF), for example, includes this unsettling factoid:

“In recent years, almost all human cases of the most lethal form of the disease, pneumonic plague, have been linked to domestic cats.” [1]

I have no way of knowing the source of ABC’s claim, as no citations are included in the brochure. But I suspect it can be traced to a CDC report published 10 years earlier, in which a more complete picture is painted.

“Before 1977, domestic cats were not reported as sources of human plague infection; however, since 1977, cats have been identified as the source of infection for 15 human plague cases. In addition, the proportion of human plague cases with primary pneumonic plague has been substantially higher among cat-associated cases (four of 15 cases) than among cases for which cats were not sources of infection (one of 236 cases).” [2]

If four out of five cases is considered “almost all,” then ABC is technically correct. But again, how about a little perspective? The fact that “the most lethal form of the disease” represented just 2 percent of all human plague cases in the U.S. between 1977 and 1994, for example. And the fact that cat-associated cases represented just 6 percent of human plague cases over that period.

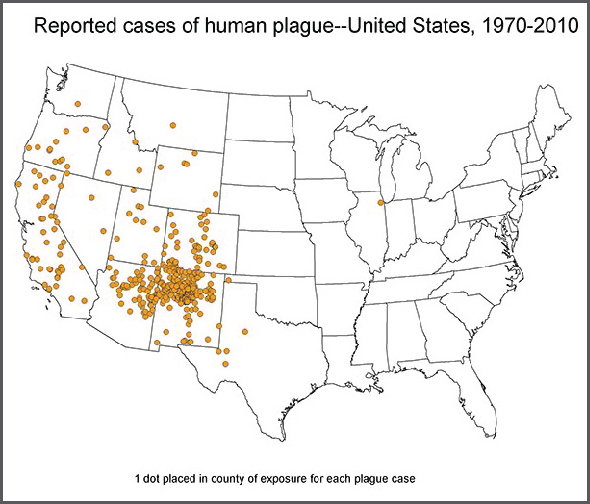

And, as the CDC’s map illustrates, the cases are concentrated geographically—a fact TNR opponents rarely acknowledge.

The last time TWS CEO/executive director Michael Hutchins mentioned the plague on the TWS blog was August 2011, referring to a case in Colorado. “One has to wonder,” complained Hutchins, “why public health practitioners aren’t more concerned about the growing numbers of feral and free-ranging cats in the U.S., or about large managed cat colonies?”

Perhaps public health practitioners are, unlike Hutchins, able to put reports of plague infection into perspective—seeing them for the rare event they are. (And perhaps they don’t buy Hutchins’ assertion—made frequently but never supported with evidence—that the number of free-roaming cats is on the rise.)

At last check, there’s no media release from ABC in response to the Oregon case. But as I say, it’s probably only a matter of time.

After all, both TWS and ABC have taken advantage of recent rabies stories to get out their anti-TNR message. (When a rabid skunk was discovered by TNR volunteers in New Mexico this April, Hutchins couldn’t resist, badly misrepresenting the connection to free-roaming cats and gloating: “I hate to say I told you so.”)

In September, ABC used World Rabies Day as an opportunity to issue a media release claiming: “Feral cat colonies bring together a series of high risk elements that result in a ‘perfect storm’ of rabies exposure.”

To their credit, neither organization has tried to capitalize—publicly, anyhow—on the recent case of typhus in Santa Ana, California. I suspect, however, that some reference to it will be tacked onto a future story aimed at scapegoating free-roaming cats.

Literature Cited

1. ABC, The Great Outdoors is No Place for Cats. 2004, American Bird Conservancy: Washington, DC. http://www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/materials/hazards.pdf

2. n.a., Human Plague—United States, 1993–1994 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1994, Centers for Disease Congtrol and Prevention: Atlanta, GA. p. 242–246. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00026077.htm