For years now, the American Bird Conservancy (ABC) has been promoting erroneous and misleading information in their tireless effort to vilify free-roaming cats. No organization has been more effective at working the anti-TNR pseudoscience into a message neatly packaged for the mainstream media, and eventual consumption by the general public. Speaking to the Wall Street Journal in 2002, Becky Robinson, co-founder and President of Alley Cat Allies, described ABC’s Cats Indoors! campaign as “a new environmental witch hunt.” [1]

In their recently released book, The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation, ABC changes tack a bit—using what the authors call “conservative” estimates of the outdoor cat population and annual predation rates, for example, to arrive at their figure of “532 million birds killed annually by outdoor cats.” [2] At the same time, they include much of the same misinformation ABC’s been promoting all along. It’s a clever strategy, really: endorsing bogus claims as valid science without having to defend them as such.

In fact, one doesn’t need to get past the book’s preface before realizing the role that science plays—or, more to the point, doesn’t play—at ABC. “We see very few issues resolved through coming to consensus on the science,” writes President and CEO George Fenwick.

“More often, science divides us. So, though we continue to need excellent science, conservationists also need to learn how to better persuade, use media effectively, and connect birds to the human condition, spirituality and ethical values.” [2]

If its section on cats is any indication, The ABC Guide is the manifestation of Fenwick’s philosophy: more style than substance, more sales than science. The authors didn’t even bother with citations and references, suggesting to readers, perhaps, that The ABC Guide is the last word on the subject. Where free-roaming cats are concerned, though, ABC has precious few answers—in part because they (still) aren’t asking the right questions.

Outdoor Cats

Referring to unattributed 2007 data, the authors of The ABC Guide—Daniel Lebbin, Michael Parr, and George Fenwick—claim that 43 percent of pet cats “have access to the outdoors.” [2] But, according to American Pet Products Association (APPA) 2008 National Pet Owners Survey, 64 percent of cats are indoor-only during the daytime, and 69 percent are kept in at night [3].

Other surveys have yielded similar results, and also indicate that, of those cats that are allowed outdoors, approximately half were outside for three hours or less each day [4, 5]. For Lebbin et al., though, these part-timers are no different from their feral relatives. Of which, “there are 60–120 million,” according to the authors. [2]

Where this figure comes from is anybody’s guess. It’s substantially higher than any other estimates I’ve seen, with one notable exception—a statement made earlier this year by an ABC official (more on that in a moment).

Feral Cat Numbers

Very little exists in terms of credible population estimates for feral cats. There are, however, many unsubstantiated claims.

Among the most popular for those interested in big numbers is the first line from David Jessup’s ironically titled 2004 paper “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife” (ironic because his “concerns” for the welfare of these cats are so plainly disingenuous): “There are an estimated 60 to 100 million feral and abandoned cats in the United States.” [6] As to the origins of Jessup’s “estimate,” again, it’s anybody’s guess, as he offers no reference.

Based on the results of a 1999 telephone survey of Alachua County, Florida, residents, Levy et al. estimated that the population of free-roaming cats represented approximately 44 percent of the county’s total population of cats. [7] Other researchers have reported similar figures for nationwide estimates. [8] By way of comparison, ABC’s estimate represents 39–56 percent of the overall population of cats in the U.S. (based on APPA’s latest figures for pet cats).

On the other hand, Merritt Clifton of Animal People, an independent newspaper dedicated to animal protection issues, makes a compelling argument that the population of feral cats in the U.S. is much smaller than is often reported, and may very well be on the decline. [9] Clifton’s estimates are derived not from surveys of homeowners feeding stray and feral cats, but from “information about the typical numbers of cats found in common habitat types, gleaned from a national survey of cat rescuers… cross-compared with animal shelter intake data.” [10] In 2003, Clifton suggested that “the winter feral cat population may now be as low as 13 million and the summer peak is probably no more than 24 million.” [10]

Population Increase

Earlier this year, ABC’s Senior Policy Advisor, Steve Holmer, told the Los Angeles Times, “The latest estimates are that there are about . . . 160 million feral cats [nationwide].” When pressed for details, Holmer referred me to Nico Dauphine and Robert Cooper’s 2009 Partners In Flight Conference paper. Which, as it turns out, leads right back to ABC and their Cats Indoors! campaign.

Dauphine and Cooper begin their adventure in creative accounting with Jessup’s unattributed 100 million, and add to it the number of owned cats they describe as “free-ranging outdoor cats for at least some portion of the day.” [11] For which they turn to Linda Winter, former director of Cats Indoors!, and her 2004 paper in which she reports the findings of a 1997 telephone survey (commissioned by ABC) of cat owners. According to Winter, “66 percent of cat owners let their cats outdoors some or all of the time.” [12]

In fact, the survey—as reported in ABC’s brochure “Human Attitudes and Behavior Regarding Cats”—indicated that “35 percent keep their cats indoors all of the time” and “31 percent keep them indoors mostly with some outside access.” [9] The difference in wording is subtle and hampered by imprecision (it all comes down to the meaning of some), but it’s difficult not to see this as deliberately misleading on Winter’s part.

In any case, results of other surveys (described previously) suggest quite convincingly that outdoor access for the vast majority of pet cats is really very limited. Nevertheless, Dauphine and Cooper persist, arriving at a staggering “117–157 million free-ranging cats.” [11] Holmer, in turn, rounds off the upper limit, “scrubs” the pet cats from the calculation by calling them all ferals, and gets the bogus figure printed in the Times. (Gold star for Holmer!)

Lebbin et al. don’t go that far, but their “most conservative estimate of outdoor and feral cats in the U.S.”—95 million—is, given its shaky origins, no more valid than Dauphine and Cooper’s.

Predation

According to The ABC Guide, “all outdoor cats hunt and kill birds (20–30 percent of cat prey) and other small animals.” [2] No study I’m aware of has demonstrated that all cats hunt. On the contrary, some research suggests that less than half of outdoor cats hunt. Figures as low as 36–56 percent have been reported by researchers in Australia, for example. [13]

In the UK, Baker, Bentley, Ansell, and Harris reported that 77 cats returned a total of 212 prey items to 52 Bristol households participating in their pilot study, but “in each sampling period, the majority of cats (51–74 percent) failed to return any prey.” [14] The subsequent 12-month study (this time involving 186 Bristol households, 275 cats, and 495 prey items) found a similar level of apparent non-hunters: roughly 61 percent. [15]

Woods, McDonald, and Harris, also working in the UK, found that, although 91 percent of cats returned at least one item, “approximately 20–30 percent of cats brought home either no birds or no mammals.” [16] And Churcher and Lawton’s yearlong “English Village” study (involving approximately 70 cats and 1,090 documented prey items) found that that 8.6 percent of cats brought home no prey [17] (though the authors don’t specify the percentage of cats that returned no birds).

And while it’s true that cats are unlikely to return home with all they prey they catch, it’s equally true that they will bring home items they didn’t kill. Very little is known about the extent of either phenomenon, however. (Carol Fiore’s [18] attempt to unravel this mystery is plagued by methodological missteps and obvious bias; William George’s [19] comments are often interpreted as suggesting that cats return only half of what they catch, though this is incorrect.)

The Diet of Cats

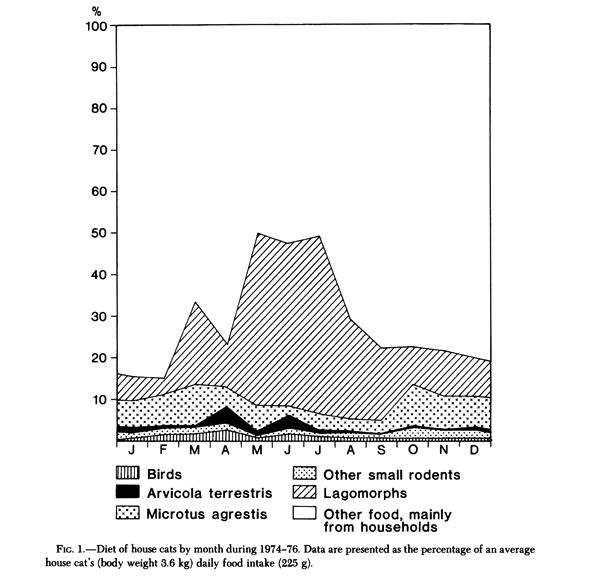

The idea that birds make up 20–30 percent of the diet of free-roaming cats is one that ABC has been promoting since 1997, when they launched Cats Indoors! But it’s no more valid now than it was then.

According to ABC’s brochure, “Domestic Cat Predation on Birds and Other Wildlife” (downloadable from their website), “extensive studies of the feeding habits of domestic, free-roaming cats… show that approximately… 20 to 30 percent [of their diet] are birds.” Ellen Perry Berkeley carefully examined—and debunked—this claim in her book, TNR Past Present and Future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement, noting that ABC’s 20–30 percent figure wasn’t based on “extensive studies” at all. [10]

In fact, just three sources were used: the now-classic “English Village” study by Churcher and Lawton [11], the infamous “Wisconsin Study,” and researchers Mike Fitzgerald and Dennis Turner’s contribution to The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour. [12]

As Berkeley points out, combining or comparing data from these three sources is entirely inappropriate. Both the English Village and Wisconsin studies report the percentage of birds returned as a portion of the “total catch,” whereas Fitzgerald reports percentage by frequency (i.e., the occurrence of birds in the stomach contents or scats of free-roaming cats).

To put this into more familiar terms, consider coffee consumption. According to the 2009 National Coffee Drinking Trends Study, 54 percent of American adults drink coffee daily—54, then, is the percentage by frequency. To say that coffee makes up 54 percent of our dietary intake—essentially ABC’s interpretation—is obviously a gross exaggeration of consumption levels. (Neither measure says anything about the supply of coffee, of course.)

Nevertheless, 13 years after ABC first published its report—and six years after Berkeley exposed the error publicly in TNR—the myth persists. So much for ABC’s commitment, spelled out in the book’s section on threats, to “address all of the major threats responsible for killing large numbers of birds, using the best information and research available, while promoting further research and monitoring where it is most needed.” [2]

Which, in turn, raises serious questions about the integrity of ABC and the people running it.

Declawed Cats

Citing Fiore’s thesis research, Lebbin at al. conclude, “de-clawed cats kill as many birds as cats with claws.” [2] Fiore herself is equally confident:

“There were seven declawed cats in the study and all but one took birds (giving a figure of 86 percent); the top predator cat was declawed. Declawing cats appears to have no effect whatsoever on the ability to hunt birds.” [18]

But, both ABC and Fiore leave out some critical details. There were, after all, only 41 cats involved in the study—hardly the kind of sampling required to make such sweeping statements.

A closer look reveals that the declawed cats were apparently responsible for killing an average of 3.6 birds/cat/year while the cats with claws had an average of 3.0. Does this mean that the declawed cats are actually superior hunters compared to the other cats? Hardly.

In addition to the sampling issue, there’s the problem inherent in using the average to describe highly skewed distributions (many cats catching few prey, while few cats catch many prey). In such instances, it’s more appropriate to use median values, which better represent “average” hunting success. [20] Doing so yields estimates of 1 bird/cat/year for the declawed cats vs. 2 birds/cat/year for the cats with claws.

So, declawed cats kill only half as many birds as those with claws? I’ll leave such indefensible claims to others.

Now, to be clear: I’m no advocate of declawing. Nor do I think it’s in the best interest of pet cats to be outdoors—especially those without claws. My point here is merely to demonstrate the flaws in ABC’s deceptively straightforward assertion; once again, ABC is more interested in a good story than they are in good science. (Their comment about declawed cats is precisely the kind of sound-bite that is easily picked up by the media, and repeated so widely that it becomes nearly impossible to trace—never mind untangle.)

Cats and Birds

As evidence of the “variable predation rates by cats,” [2] The ABC Guide refers to just four studies. And, although no citations are included, people familiar with the literature will recognize the numbers and locations immediately.

- From Christopher Lepczyk’s dissertation work, the authors somehow extract a figure of 35.5 birds/cat/year, near the low end of Lepczyk’s own estimate of “between 0.7 and 1.4 birds per week.” [21] But Lepczyk’s research suffers from a range of problems—both in terms of his methods and analysis—that inflate his estimated predation rates. (Interestingly, ABC’s Fenwick and Winter are among those Lepczyk thanks “for helpful and constructive reviews” in the Acknowledgements section.)

- Another of the predation rates included in The ABC Guide is the more moderate 15 birds/cat/year from Crooks and Soulé’s 1999 paper [22]. But here, too, there are flaws that lead to bloated predation levels.Like Lepczyk, Crooks and Soulé asked residents to estimate annual levels of prey returned home by their cats (in contrast to some studies in which actual prey items are recorded and/or collected). But such guesswork becomes less accurate as estimates increase. David Barratt found that “predicted rates of predation greater than about ten prey per year generally over-estimated predation observed” [20]. At the levels reported by Crooks and Soulé—an average of 56 total prey items (including birds, mammals, etc.) per year—predicted rates were often twice actual predation rates.

Also, Crooks and Soulé seem (not enough detail is provided in their paper to be certain) to have used a simple average in their calculations, perhaps doubling true predation levels. Taken together, these factors suggest that actual predation levels might be just a quarter of those suggested by Crooks and Soulé.

- The third study—easily the most rigorous of the four—with a predation rate of 9.6 birds/cat/year, comes from Woods et al. The researchers, having recruited study participants solely from The Mammal Society, allow that they “may have focused on predatory cats,” and ask that their results be “treated with requisite caution.” [16] They also make clear that their estimated predation rates “do not equate to an assessment of the impact of cats on wildlife populations” [16] (more on that shortly)

- Finally, there is the—seemingly inevitable—reference to the Wisconsin Study, though for some reason (again, without explanation) Lebbin et al. have adjusted Coleman and Temple’s figures of 28–365 birds/cat/year downward: “between 5.6 and 109.5.” [2]In this case, the details hardly matter. The Wisconsin Study isn’t actually a study at all; no predation data or findings were ever published. Coleman and Temple’s “estimates”—widely circulated as valid research, thanks in part to ABC—were nothing more than back-of-the-envelope calculations. “Our best guesses,” as the authors themselves admit, “at low, intermediate and high estimates of the number of birds killed annually by rural cats in Wisconsin.” [23]

“Those figures were from our proposal,” Temple told The Sonoma County Independent. “They aren’t actual data; that was just our projection to show how bad it might be.” [24]

Sixteen years later, though, ABC is still trying to make “actual data” out of “not actual data.” (Granted, they have backed off from Coleman and Temple’s high estimate, but no mathematical adjustments can transform these flawed, biased guesses into valid research findings.)

Cats as Hunters

Contrary to popular myth, evidence suggests that cats are not quite the hunters they’ve been made out to be. Fitzgerald and Turner suggest that the hunting behavior of cats leads to many “failures,” and, as a result, “many cats soon give up bird hunting altogether.” [25]

“Primarily, all cats hunt both birds and rodents with equal zeal,” observed German zoologist Paul Leyhausen, “and many obviously prefer eating birds.” But, argues Leyhausen (1916–1998), who spent the bulk of his career studying the behavior of cats, “they cannot catch them as easily, and for this reason with increasing experience may soon give up hunting birds.” [26]

“However, our town cats today are often compelled, because of the almost total absence of rodents in their territory to concentrate on chasing birds in order to discharge their pent-up hunting propensities. Even in these circumstances, however, cats are not capable of seriously endangering the songbird population of a substantial area. They almost always catch only old, sick or young specimens. But three quarters of the young birds must perish anyway, since the size of the population in an area remains fairly constant on an average over the years… During years in the field I have observed countless times how cats have caught a mouse or a rat and just as often how they have stalked a bird. But I never saw them catch a healthy songbird that was capable of flying. Certainly it does happen, but, as I have said, seldom. I should feel sorry for the average domestic cat that had to live solely on catching birds.” [26]

Although few predation studies have examined the hunting behavior of cats belonging to managed colonies, those that have are revealing. Reporting on their study of free-roaming cats in Brooklyn, Calhoon and Haspel write: “Although birds and small rodents are plentiful in the study area, only once in more than 180 [hours] of observations did we observe predation.” [27]

Castillo and Clarke, though highly critical of TNR (“This method is not an effective means to control the population of unwanted cats and confirms that the establishment of cat colonies on public lands encourages illegal dumping and creates an attractive nuisance.” [28]), documented little predation in the two Florida parks they used for their study (the focus of which was TNR efficacy, not predation). Over the course of approximately 300 hours of observation (this, in addition to “several months identifying, describing, and photographing each of the cats living in the colonies” [28] prior to beginning their research), Castillo and Clarke “saw cats kill a juvenile common yellowthroat and a blue jay.” [28]

“Cats also caught and ate green anoles, bark anoles, and brown anoles. In addition, we found the carcasses of a gray catbird and a juvenile opossum in the feeding area.” [28]

Another study conducted in a public park, this one in Alameda County, California, also reported low levels of apparent predation of birds (though researcher Cole Hawkins makes every attempt to suggest otherwise). Of 120 scat samples found by searching the “cat area” of Hawkins’ study site, “65 percent were found to contain rodent hair and 4 percent feathers.” [2] This finding comes toward the end of the study, when the cat population was at its greatest (22 were sighted)—and still, only 4 percent contained feathers. And this could easily represent one cat and one bird (and, strictly speaking, even this is not evidence of actual predation, as the bird(s) could have been scavenged).

Impact

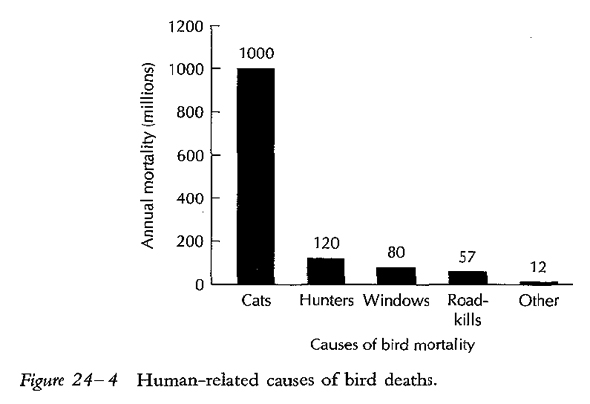

To arrive at their figure of “532 million birds killed annually by outdoor cats,” Lebbin et al. multiply “the most conservative predation rate (5.6 birds per cats per year) by the most conservative estimate of outdoor and feral cats in the U.S. (95 million).” [2] They go on to suggest that “the actual number” is “likely… much higher,” [2] though, of course, they ignore or overlook all the errors and misrepresentations bound up in their basic calculation.

Even setting all that aside, the question remains: What impact does predation by cats have on bird populations?

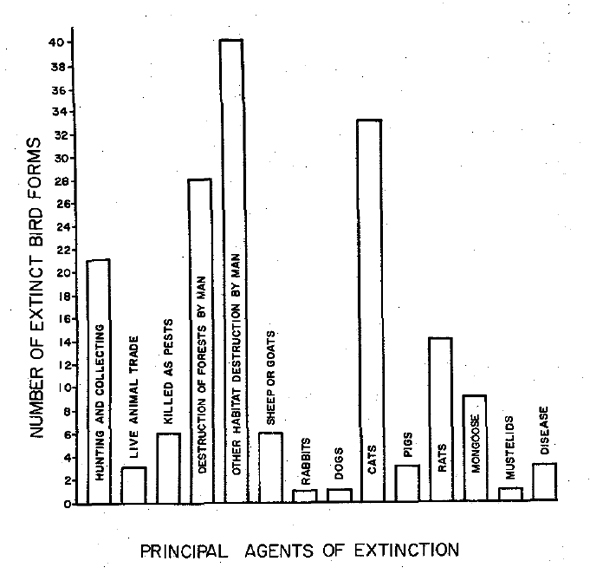

Islands and Continents

Here, the authors focus mostly on the extinction of seabirds linked to the presence of feral cats on islands. I’m only vaguely familiar with the examples they cite, but if the case of the Stephens Island Wren is any indication, the stories are far more complex than ABC suggests. [see, for example, 29 and 30]

But, as Fitzgerald and Turner point out, “because the range of prey available on islands differs markedly from that on the continents the two groups, continents and islands, are treated separately.” [25]

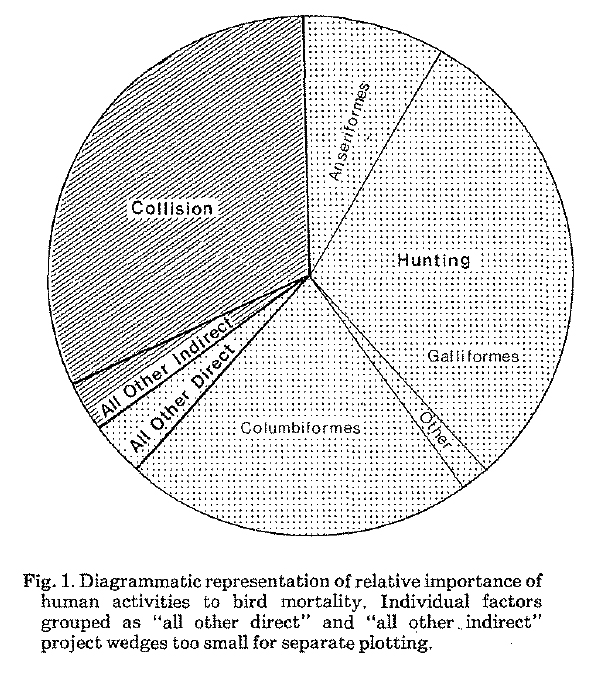

And when it comes to the impact of cats on continental bird populations, ABC highlights rare and endangered species—but ignores entirely two key points. First, as was mentioned previously, even high rates of predation do not equate to population declines.

Referring to the estimated 30 percent of House Sparrow mortality attributed to cat predation in the English Village study, Gary Patronek emphasizes the importance of viewing such predation in the larger context. “When the birds were counted,” writes Patronek, former Director of the Center for Animals and Public Policy at the Cummings School, and one of the founders of the Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium, “they represented the postwinter population prior to hatching of spring chicks. By the year’s end, the actual sparrow population in the village numbered in the thousands, and the 130 birds caught represented about 5 percent of that number.” [31]

Compensatory vs. Additive Predation

Then there is the critical distinction between compensatory and additive predation, something Churcher himself alluded to: “I don’t really go along with the idea of cats being a threat to wildlife. If the cats weren’t there, something else would be killing the sparrows or otherwise preventing them from breeding.” [32]

Two very interesting studies have generated compelling evidence that birds killed by cats are, on average, significantly less healthy than those killed through non-predatory events (e.g., collisions with buildings). [15, 33] In other words, these birds probably weren’t going to live long enough to contribute to the overall population numbers; predation was compensatory rather than additive. Relative to population impacts, then, the “accounting” of bird kills is far more complex than ABC suggests.

Additional Evidence

Many researchers have disputed the kind of broad, overreaching claims Lebbin et al. make about the impact of cats on bird population (and wildlife in general).

Biologist C.J. Mead, reviewing the deaths of “ringed” (banded) birds reported by the British public, suggests that cats may be responsible for 6.2–31.3 percent of bird deaths. “Overall,” writes Mead, “it is clear that cat predation is a significant cause of death for most of the species examined.” Nevertheless, Mead concludes:

“there is no clear evidence of cats threatening to harm the overall population level of any particular species… Indeed, cats have been kept as pets for many years and hundreds of generations of birds breeding in suburban and rural areas have had to contend with their predatory intentions.” [34]

Mike Fitzgerald and Dennis Turner come to essentially the same conclusion: “We consider that we do not have enough information yet to attempt to estimate on average how many birds a cat kills each year. And there are few, if any studies apart from island ones that actually demonstrate that cats have reduced bird populations.” [25]

In the context of TNR, however, focusing on such figures may be missing the point. “If the real objection to managed colonies is that it is unethical to put cats in a situation where they could potentially kill any wild creature,” writes Patronek, “then the ethical issue should be debated on its own merits without burdening the discussion with highly speculative numerical estimates for either wildlife mortality or cat predation.” [35]

“Whittling down guesses or extrapolations from limited observations by a factor of 10 or even 100 does not make these estimates any more credible, and the fact that they are the best available data is not sufficient to justify their use when the consequence may be extermination for cats… What I find inconsistent in an otherwise scientific debate about biodiversity is how indictment of cats has been pursued almost in spite of the evidence, and without regard to the differential effects of cats in carefully selected, managed colonies, versus that of free-roaming pets, owned farm cats, or truly feral animals. Assessment of well-being for any species is an imprecise and contentious process at best. Additional research is clearly needed concerning the welfare of these cats.” [35]

Trap-Neuter-Return

“Many well-intentioned but misguided people,” write Lebbin et al. “exacerbate feral cat problems through a technique called Trap, Neuter, Release (TNR), whereby colony cats are caught, spayed or neutered, and then returned to colonies to be fed by volunteers.” [2] Here, the authors trot out a classic verbal swipe, using the term Release instead of Return, implying a certain lack of planning, or even abandonment (with its legal implications).

They also imply that ABC is a resource for the “misguided.”

From The ABC Guide, the caption reads: “Managed feral cat colonies are a hazard to birds and attract the dumping of additional unwanted cats.” In fact, the photographer, Tina Lorien, tells me that these cats were photographed on the Island of Crete, where, it seems, even spayed/neutered pet cats are rather rare.

“Despite its apparent appeal,” Lebbin et al. continue, “few colonies managed under this system shrink, as the program takes more time than most volunteers are able to give, some cats are never caught, and the colonies often become dumping grounds for more unwanted cats.” [2]

Resources

Their claim that TNR programs are ineffective due to limited resources is unsubstantiated. More important, though, they ignore the fact that any feral cat management program is resource-intensive (as is any conservation effort, of course). Several successful TNR programs have been documented (see below), and countless more operate quietly, out of the spotlight.

It’s important to point out, too, that TNR is typically funded through private donations and the out-of-pocket purchases of volunteers. Trap-and-kill, on the other hand, is more likely to rely entirely on local tax dollars.

Sterilization

Their suggestion that all the cats need to be sterilized also lacks support. One often-cited population modeling study—included here more as a reference point than anything else—found that, in order to reduce colony population, approximately 75 percent of fertile cats would need to be sterilized. [36] However, this figure from Andersen, Martin, and Roemer takes into account no adoptions, though the authors point out that adoptions “are similar in effect to euthanasia because these cats are permanently removed from the free-roaming cat population.” [36]

Nor do Andersen et al. consider emigration between cat colonies, though they concede that “a substantial number of owned cats are reported to be adopted strays.” [36] “Substantial” is right—in 2003, Clifton suggested that “up to a third of all pet cats now appear to be recruited from the feral population.” [10]

TNR Successes

Though Lebbin et al. refuse to acknowledge it, TNR has had its share of successes. A 10-year TNR program in Rome, for example, yielded a “16–32 percent decrease on total cat number” across 103 managed colonies. [37] Detractors [38] like to focus on authors’ suggestion that “all these efforts without an effective education of people to control the reproduction of house cats (as a prevention for abandonment) are a waste of money, time and energy.” [37]

In fact, given the 21 percent rate of immigration “due to abandonment and spontaneous arrival,” [37] this colony reduction is quite remarkable. And, as Julie Levy, Maddie’s Professor of Shelter Medicine in the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine, points out, “such a decline is still beneficial to wildlife if no better alternative is available.” [39] (The “alternatives” ABC proposes—outlined below—are, at best, exactly that: no better.)

Levy, Gale, and Gale reported a 66 percent decline in the population of managed colonies on the University of Central Florida campus between 1991 and 2002, despite the arrival of stray or abandoned cats. [40] (In their paper, Levy et al. cite several other success stories.) And, in their telephone survey of 101 north-central Florida colony caretakers, Centonze and Levy reported “a 27 percent decrease in mean colony size within less than one year of beginning neutering.” [41]

One of the best-known TNR programs is ORCAT, run by the Ocean Reef Community Association, which, according to a 2004 paper, had reduced “overall population from approximately 2,000 cats to 500 cats.” [42] According to the ORCAT website, the population today is approximately 350, of which only about 250 are free-roaming.

Any TNR program contends with the unfortunate (and illegal) dumping of cats. But to suggest that TNR invites abandonment of cats is ridiculous. I’ve seen no research supporting such a claim. If people are determined to abandon their pet cat(s), I fail to see how the presence or absence of a nearby TNR program will affect that decision. On the other hand, cats dumped near a managed colony are far more likely to be adopted and/or sterilized—thereby mitigating their potential impact on the overall population of unowned cats.

Finally, it’s important to note that, although rapid decline—and eventual elimination through attrition—of managed colonies is the goal of TNR (and apparently the only acceptable outcome for the authors of The ABC Guide), reduced growth is not without its benefits. “Population stabilization,” writes Levy, is “a valid metric given that the status quo for unsterilized cats is rapid population growth.” [39]

Alternatives to TNR

Given their ongoing criticism of TNR, one might expect ABC to offer an alternative method of feral cat management—an approach against which to measure TNR (and against which TNR would, presumably, prove inferior). For the most part, though, ABC sidesteps the issue.

“Neutering and spaying pet cats,” write Lebbin et al., “is a humane method for reducing cat over-population.” True enough, but that doesn’t address the sizable population of unowned cats. Although The ABC Guide calls for readers to “make TNR and the feeding of cat colonies illegal,” [2] there’s no recommendation for what should be done with all of these cats.

I put this question to Lebbin and Parr during an ABC webinar celebrating the launch of the book earlier this month. “What we recommend,” said Parr, Vice President of ABC, “as an alternative to [TNR], is not abandoning cats in the first place.” Again, I don’t think there’s any disagreement on this point. Parr continued:

“Other options would be to house those cats in shelters or outdoor sanctuaries which could be managed. Clearly, it’s a huge problem, and the solutions to this are going be things we going to have to work together on for a long period of time, but certainly that would be my first reaction to that question.”

Really, we’re back to sanctuaries? Is this the best ABC has to offer? Almost.

Trap-and-Remove

In their book, Lebbin et al. point out, with obvious pride, that, “By 2004, feral cats had been successfully removed from at least 48 islands worldwide” (there’s another euphemism: removed). [2] A particular “success” is Ascension Island, where, the authors maintain, feral cats had reduced seabird numbers “by 98 percent, from 200 million to 400,000.” [2] As a result of “a multi-year eradication effort that began in 2001,” [2] birds have begun to return.

But, as is often the case, what’s left out of the story is far more interesting than what included.

Detailed accounts of feral cats eradication Marion Island provide a glimpse of the horrors involved. A 1992 paper reports 872 cats shot and 80 more trapped during 14,725 hours of hunting. “Present action” included “mass trapping and poisoning, and the possible use of trained dogs [was] being investigated.” [43] This was after the highly contagious feline panleucopenia virus (feline distemper) had been introduced to the island’s feral cat population, reducing the population by an average 29 percent annually between 1977 and 1982. [44]

On Macquarie Island successful eradication has had “dire” [45] consequences in the form of rapidly increasing rabbit and rodent populations. “In response, Federal and State governments in Australia have committed AU$24 million for an integrated rabbit, rat and mouse eradication programme.” [45]

Given the extent to which conservation efforts backfired on Macquarie Island—less than 50 square miles in size—one can only imagine the consequences and expense (to say nothing of the protests!) of a similar attempt in the continental U.S. But according to ABC, it seems to be either this or sanctuaries—for a population of feral cats they claim to be 60–120 million strong.

(To be fair, Lebbin et al. do offer this concession: “In some cases, invasive or overabundant species may not need to be eradicated, but simply reduced to levels such that they no longer pose a serious threat to native endangered species.” [2] Given their staunch opposition to TNR, however, I suspect this “offer”—which in any case would mean the killing of many millions of cats—does not apply to feral cats.)

The Current Approach

We do have some sense of how ineffective “traditional” feral cat management—a mix of trap-and-kill and inaction—has been. In an interview with Animal Sheltering magazine, Mark Kumpf, President of the National Animal Control Association President from 2007 to 2008, described this approach as “bailing the ocean with a thimble,” suggesting, too, that “the traditional methods that many communities use… are not necessarily the ones that communities are looking for today.” [46]

Clifton goes further, suggesting that trap-and-kill has actually backfired: “Regardless of motive,” writes Clifton, “the effect on the feral cat population replicates natural predation: the most frequent victims are the very young, the old, the disabled, and the ill. The healthiest animals usually escape to breed up to the carrying capacity of the habitat, if they can.” [10]

“Responding to the intensified mortality,” Clifton continues, “felis catus now bears an average litter of four. Nearly seven centuries of killing cats doubled the fecundity of the species.” [10]

Accountability

What Becky Robinson called a “new environmental witch hunt,” [1] I like to think of as a Trojan Horse. Disguised as good advice for responsible cat owners, ABC’s Cats Indoors! campaign has, since 1997, been used more to combat TNR than anything else.

With the publication of The ABC Guide, the authors had a chance to right some past wrongs by coming clean about the research surrounding predation, wildlife impacts, and TNR, as well as the true implications of their call to “make TNR and the feeding of cat colonies illegal.” [2] Instead, they elected for business as usual.

Facts vs. Human Connection

In doing so, ABC missed a golden opportunity to use its enormous influence for moving the discussion forward. (More recently, ABC took another big step backwards by endorsing a deeply flawed and irresponsible paper released by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, once again sacrificing their integrity for some easy PR.)

But Fenwick, who’s been President and CEO since ABC’s founding in 1994, doesn’t seem to get it. “What have we learned about the opposition?” he asks rhetorically in the book’s preface.

“For one thing, every point of view has its own science and economics to support its contentions, whether it be pro- or anti- pesticide use, free-roaming cats, bird collisions with glass or towers, conflicts with fisheries, land conversion, wind energy, mining, timbering, climate change, or any other issue we consider in addressing bird conservation…” [2]

Fenwick seems to be suggesting that “the opposition” has its own science and economics, whereas ABC has, on its side: Science and Economics (a truly untenable position, in light of a recent ABC press release).

“Facts alone will not win these battles,” he continues, “but human connection might.”

Communication vs. Misinformation

I have to agree with Fenwick that facts alone are insufficient to engage the general public. It’s difficult, for instance, to convey the critical nature of climate change in terms of ocean temperatures rising a couple of degrees Celsius (a figure I use here only to make a point). Explain to people how deep the water may rise in their city or neighborhood, however, and you’re liable to get their attention.

But that’s not what ABC is doing. They have effectively dismissed any and all rigorous science, choosing instead to broadcast as loudly as possible their increasingly dire message—in spite of the science.

Fenwick’s analogy is not climate change, but human health and welfare:

“…no matter the issue, our opposition will unfailingly question our priorities. So, they ask, ‘Why are you blaming __________ when we know habitat loss is the real problem?’ when I am asked these questions, I reply first that we continue to add to our base of knowledge and thus improve decisions affecting bird populations; second, if winning the debate translates to financial gain for the debater, then that position cannot be truly unbiased; and third, isn’t it analogous that if heart disease is the greatest mortality factor in our species, then why do we spend so much money combating cancer and other diseases, poverty and hunger? Solving any single problem—for birds or humans—is insufficient for our cause. Thoughtful people understand that it is critical that we fight for birds and humans across the full, broad front of issues.” [2]

Fenwick’s medical research analogy is an interesting one, but not in the way he intended. Actually, I’m reminded of David Freedman’s profile of John Ioannidis, professor at the University of Ioannina medical school’s teaching hospital, which appeared in last month’s Atlantic. In the piece, Freedman describes a provocative 2005 article that garnered Ioannidis worldwide attention:

“The article spelled out his belief that researchers were frequently manipulating data analyses, chasing career-advancing findings rather than good science, and even using the peer-review process—in which journals ask researchers to help decide which studies to publish—to suppress opposing views.” [47]

Obviously not the image Fenwick was trying to convey—but far more fitting.

Attacking “the full, broad front of issues” simultaneously makes perfect sense, but promoting erroneous and deceptive scientific claims in order to marshal the support necessary is unethical, plain and simple.

We’re not talking about cancer research distracting us from research into heart disease, to use Fenwick’s metaphor. No, what he and ABC are doing—in their relentless persecution of free-roaming cats, at least—is akin to funneling critical resources into the bottling and marketing of snake oil:

There’s no science behind it, and no remedy in its consumption—whatever the dosage.

Literature Cited

1. Sterba, J.P. (2002, October 11). Tooth and Claw: Kill Kitty? Wall Street Journal, p. A.1,

2. Lebbin, D.J., Parr, M.J., and Fenwick, G.H., The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation. 2010, London: University of Chicago Press.

3. APPA, 2009–2010 APPA National Pet Owners Survey. 2009, American Pet Products Association: Greenwich, CT.

4. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.1541

5. Lord, L.K., “Attitudes toward and perceptions of free-roaming cats among individuals living in Ohio.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2008. 232(8): p. 1159-1167. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.232.8.1159

6. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1377

7. Levy, J.K., et al., “Number of unowned free-roaming cats in a college community in the southern United States and characteristics of community residents who feed them.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 223(2): p. 202-205. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.223.202

8. Patronek, G.J. and Rowan, A.N., “Editorial: Determining dog and cat numbers and population dynamics.” Anthrozoös. 1995. 8(4): p. 199–204.

9. Clifton, M. (2003) Roadkills of cats fall 90% in 10 years—are feral cats on their way out? http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/03/11/roadkills1103.html Accessed May 23, 2010.

10. Clifton, M. Where cats belong—and where they don’t. Animal People 2003 [cited 2009 December 24]. http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/03/6/wherecatsBelong6.03.html.

11. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2009. p. 205–219. http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/pif/pubs/McAllenProc/articles/PIF09_Anthropogenic%20Impacts/Dauphine_1_PIF09.pdf

12. Winter, L., “Trap-neuter-release programs: the reality and the impacts.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1369-1376. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1369

13. Fougere, B. Cats and wildlife in the urban environment—A review. in Urban Animal Management Conference. 2000.

14. Baker, P.J., et al., “Impact of predation by domestic cats Felis catus in an urban area.” Mammal Review. 2005. 35(3/4): p. 302-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.2005.00071.x

15. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2008.00836.x

16. Woods, M., McDonald, R.A., and Harris, S., “Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain.” Mammal Review. 2003. 33(2): p. 174-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2907.2003.00017.x

17. Churcher, P.B. and Lawton, J.H., “Predation by domestic cats in an English village.” Journal of Zoology. 1987. 212(3): p. 439-455. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1987.tb02915.x

18. Fiore, C.A., The Ecological Implications of Urban Domestic Cat (Felis catus) Predation on Birds In the City of Wichita, Kansas, in College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. 2000, Wichita State University: Wichita, Kansas.

19. George, W., “Domestic cats as predators and factors in winter shortages of raptor prey.” The Wilson Bulletin. 1974. 86(4): p. 384–396. http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Wilson/v086n04/p0384-p0396.pdf

20. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by house cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. II. Factors affecting the amount of prey caught and estimates of the impact on wildlife.” Wildlife Research. 1998. 25(5): p. 475–487.

21. Lepczyk, C.A., Mertig, A.G., and Liu, J., “Landowners and cat predation across rural-to-urban landscapes.” Biological Conservation. 2003. 115(2): p. 191-201. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V5X-48D39DN-5/2/d27bfff8454a44161f8dc1ad7cc585ea

22. Crooks, K.R. and Soule, M.E., “Mesopredator release and avifaunal extinctions in a fragmented system.” Nature. 1999. 400(6744): p. 563–566. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v400/n6744/abs/400563a0.html

23. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., On the Prowl, in Wisconsin Natural Resources. 1996, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources: Madison, WI. p. 4–8. http://dnr.wi.gov/wnrmag/html/stories/1996/dec96/cats.htm

24. Elliott, J. (1994, March 3–16). The Accused. The Sonoma County Independent, pp. 1, 10.

25. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

26. Leyhausen, P., Cat behavior: The predatory and social behavior of domestic and wild cats. Garland series in ethology. 1979, New York: Garland STPM Press.

27. Calhoon, R.E. and Haspel, C., “Urban Cat Populations Compared by Season, Subhabitat and Supplemental Feeding.” Journal of Animal Ecology. 1989. 58(1): p. 321–328.

28. Castillo, D. and Clarke, A.L., “Trap/Neuter/Release Methods Ineffective in Controlling Domestic Cat “Colonies” on Public Lands.” Natural Areas Journal. 2003. 23: p. 247–253.

29. Galbreath, R., “The tale of the lighthouse-keeper’s cat: Discovery and extinction of the Stephens Island wren (Traversia lyalli).” Notornis. 2004. 51: p. 193–200.

30. Medway, D.G., “The land bird fauna of Stephens Island, New Zealand in the early 1890s, and the cause of its demise.” Notornis. 2004. 51: p. 201–211.

31. Patronek, G.J., “Free-roaming and feral cats—their impact on wildlife and human beings.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1998. 212(2): p. 218–226.

32. n.a., What the Cat Dragged In, in Catnip. 1995, Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine: Boston, MA. p. 4–6.

33. Møller, A.P. and Erritzøe, J., “Predation against birds with low immunocompetence.” Oecologia. 2000. 122(4): p. 500-504.

34. Mead, C.J., “Ringed birds killed by cats.” Mammal Review. 1982. 12(4): p. 183-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.1982.tb00014.x

35. Patronek, G.J., “Letter to Editor.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1996. 209(10): p. 1686–1687.

36. Andersen, M.C., Martin, B.J., and Roemer, G.W., “Use of matrix population models to estimate the efficacy of euthanasia versus trap-neuter-return for management of free-roaming cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(12): p. 1871-1876. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1871

37. Natoli, E., et al., “Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy).” Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2006. 77(3-4): p. 180-185. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TBK-4M33VSW-1/2/0abfc80f245ab50e602f93060f88e6f9

38. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap–Neuter–Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894.

39. Levy, J.K., Comments Re: “Critical Assessment”, Personal Communication. July 21, 2010.

40. Levy, J.K., Gale, D.W., and Gale, L.A., “Evaluation of the effect of a long-term trap-neuter-return and adoption program on a free-roaming cat population.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(1): p. 42-46. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.42

41. Centonze, L.A. and Levy, J.K., “Characteristics of free-roaming cats and their caretakers.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2002. 220(11): p. 1627-1633. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2002.220.1627

42. Levy, J.K. and Crawford, P.C., “Humane strategies for controlling feral cat populations.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1354-1360. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1354

43. Bloomer, J.P. and Bester, M.N., “Control of feral cats on sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Indian Ocean.” Biological Conservation. 1992. 60(3): p. 211-219. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V5X-48XKBM6-T0/2/06492dd3a022e4a4f9e437a943dd1d8b

44. Rensburg, P.J.J.v., Skinner, J.D., and van Aarde, R.J., “Effects of Feline Panleucopaenia on the Population Characteristics of Feral Cats on Marion Island.” Journal of Applied Ecology. 1987. 24: p. 63–73.

45. Bergstrom, D.M., et al., “Indirect effects of invasive species removal devastate World Heritage Island.” Journal of Applied Ecology. 2009. 46(1): p. 73-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01601.x

46. Hettinger, J., Taking a Broader View of Cats in the Community, in Animal Sheltering. 2008. p. 8–9. http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/broader_view_of_cats.pdf

47. Freedman, D.H., Lies, Damned Lies, and Medical Science, in The Atlantic. 2010: Boston. p. 76–86. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/print/2010/11/lies-damned-lies-and-medical-science/8269/

Evidence of cats as pets? In

Evidence of cats as pets? In