On October 24th, Nico Dauphine is scheduled to appear in court, charged with attempted animal cruelty related to the poisoning of cats in her Columbia Heights neighborhood. (The latest continuance, requested by the prosecution and granted earlier this month, pushes the trial date back two full months.)

It won’t be the first time her “involvement” with cats has landed her in front of a judge.

Three years ago, while she was a PhD student at the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, Dauphine was in an Athens-Clarke County court seeking a judgment against a woman whose cat she’d trapped and turned in to the Athens Area Humane Society. I don’t know that her testimony will have any bearing on the case brought by the Washington Humane Society, but it speaks volumes about her attitude toward cats—owned and feral alike (and contradicts the statement made by her attorney following her arrest in May: “her whole life is devoted to the care and welfare of animals”).

Her testimony also raises additional questions about her willingness and/or ability to be truthful, even under oath. (I say additional because, as I’ve pointed out more than once, Dauphine’s professional work is simply indefensible in terms of its scientific underpinnings—as she demonstrated in the collection of “facts” she complied for the Spring Issue of The Wildlife Professional and in her infamous “Apocalypse Meow” presentation to an audience of students and local birders at Warnell in 2009.)

The Case

What follows is an edited version of the transcribed court proceedings—focusing on testimony by both Dauphine and the witness for the defense. The names of the people involved (other than Dauphine’s, obviously) have been omitted (as denoted by […]) throughout. (Note: As a matter of convenience, I refer to the cat’s owner as the defendant in the case; in fact, I’m not sure that’s the correct term for a dispute brought before a magistrate court.)

A little background: The defendant’s cat (its rhinestone color clearly indicating that it was somebody’s pet) had been missing for 16 days when Dauphine turned it in to the Athens Area Humane Society. Out of frustration and a determination to make public Dauphine’s trapping activities, the defendant created a blog/website (taken down voluntarily after the court hearing “to make it all go away,” as one of the people involved put it to me recently).

Dauphine’s Testimony I

The proceedings began with the judge magistrate explaining to the defendant the process and the options available to her:

…my decision today is to decide whether or not to issue an arrest warrant against you for simple assault, for terroristic threats, or for any other criminal activity that I hear, or to issue a good behavior bond against you.

Now, I could not arrest you for anything, hold the matter under advisement and just order you to do certain things and not do certain things, and as long as you abide by the terms of my order, you’ll not be arrested—but if you violate my order, then I can arrest you on these charges and any other future charges that might happen. Or I could decide that you did nothing wrong and dismiss it altogether. Those are the choices that I have this morning. Do you understand those choices?

The defendant agreed, and both parties were sworn in. Dauphine then described the series of events that led to her appearance in court—beginning with her April 15 visit to the Athens Area Humane Society, when she turned in eight cats—one of which belonged to the defendant. There, she was “confronted” by an AAHS volunteer who was “very aggressive and angry.”

“… she said that she didn’t want me to bring cats there, and that… if any of the cats belonged to them, they would be very angry. She said she was going to try to come after me for animal cruelty, and made a number of other threats.”

Three days later, Dauphine received a call from AAHS.

“They said that that morning, Friday morning the 18th, they had gotten a call from a woman who lived in an apartment complex on Barnett Shoals—that this woman had picked up a cat… that I had trapped… They warned me that this person might come to my house and hurt me.”

Dauphine then described her subsequent interactions with AAHS and the police, as well as her discovery of the blog created by the defendant. The judge magistrate then asked Dauphine about her trapping activities.

Judge Magistrate: So, have you ever gone onto the property at Cambridge Apartments and set traps for animals?

Nico Dauphine: I have not trapped there. I have several friends there and have been on the property many, many times.

JM: But you never set a trap for animals?

ND: Correct.

JM: And so the animals that you took to the shelter on April 15—how many were there?

ND: There were—I had eight cats with me.

JM: Eight cats?

ND: That’s correct.

JM: And where did you get them from?

ND: They were from—one or two were from Tivoli Apartments.

JM: Timberly?

ND: Tivoli Apartments, which is on Cedar Shoals: T-I-V-O-L-I.

JM: Oh yeah, and how did you get them?

ND: You set humane live traps and you put food in them and the animal goes in.

JM: Do you live at Tivoli?

ND: No, my friend […] lives at Tivoli.

JM: So why would you do that at Tivoli if you don’t live there?

ND: Oh, I do it basically as a community service, because I volunteered at Athens-Clarke County Animal Control for many years, and they’ve told me that one of their big problems that there’s no public service to pick up cats, but a lot of people have concerns about stray cats around.

JM: So it’s your mission to just go to apartment complexes and pick up stray cats and take them to the animal shelter?

ND: My mission is, when people—well, I mean, I have other things that I do—

JM: Let’s just talk about this one.

ND: Okay. If people ask me—I’ve had a number of people ask me to help them if they have cats on their property.

JM: Are you doing it for the landlord or are you doing it for the tenants?

ND: I’m doing—well yeah, either way.

JM: But suppose the cats belong to somebody?

ND: Well then the animal—they can be reunited with their animals at the animal shelter.

JM: Why do you make people go through that though? I don’t understand. You just go from apartment to apartment just taking up animals and taking them to the shelter?

ND: Only if people are concerned about cats there and they ask me to help them.

JM: So you took eight on April 15th—which, you got one to two from Tivoli, and where did the others come from?

ND: A couple came from my neighborhood.

JM: Which is where?

ND: East Meadow Drive…

JM: And—

ND: And the others came from off Peter Street at an address of a colleague of mine there.

JM: So who gave you permission on Peter Street?

ND: The colleague of mine.

JM: And was that—the animal is picked up at your colleague’s house, or just along the street?

ND: Yeah—no, at his house he has a lot of stray cats that come around. He doesn’t know.

JM: And so he doesn’t want them there so you set the humane traps and—

ND: That’s correct.

JM: —pick up the animals and take them to the shelter?

ND: That’s correct.

JM: That’s a new one for me. Okay. So this person that created this website is accusing you of having taken animals from Cambridge Apartments?

ND: Mmm-hmm.

JM: So have you ever set at trap at Cambridge Apartments to pick up animals from there?

ND: No, I haven’t.

JM: Okay. And the website accuses you of having set traps for animals for years. So have you been doing this for quite a while?

ND: No. I’ve only been doing it—I’ve done it at my own home which I own for about two years but I’ve only started helping other people if they need help for about six or eight months, something like that.

JM: Okay.

ND: I’ve also had the police ask me for help because it’s—there is no public service, and sometimes people leave a house with 50 cats. This happened recently. I know a number of people in the same situation.

(A search of the Banner-Herald for the first half of 2008 reveals only one possible incident fitting Dauphine’s description: “Wilford Bradford Sims, 48, pleaded guilty to 51 counts of misdemeanor animal cruelty… for leaving dozens of cats to fend for themselves in a house he abandoned” in the fall of 2007. According to the paper, although “investigators at the time called it one of the worst cases of animal neglect they’d seen,” all of the cats “found homes, including several that became barn cats, according to the Humane Society.” [1] Was Dauphine implying that she was somehow involved?)

JM: So do you work for the animal shelter, or you do this on your own?

ND: I work for the Forestry School and so we have access to humane live traps through them and—

JM: You use their traps?

ND: Uh-huh, and I’ve done a lot of volunteer work for Animal Control, and that’s how I learned about the whole situation and problem.

JM: Yeah.

ND: They say they get calls all the time—people concerned about cats and they want them to be picked up so they can be—they can find homes, they can get adopted, they can be reunited with their owners, but there’s no public service to do that.

JM: So are you aware of any cats that you’ve picked up that have been killed by the—because they had too many because—

ND: The—you know—the Athens Area Humane Society has a policy of not—

JM: Euthanizing them?

ND: —they do not euthanize socialized cats, period. So there’s never been a socialized cat that I’ve picked up that’s been killed. In fact, by contrast, I think 24 cats I’ve brought in have been able to find homes—new homes—be adopted because they were strays and they were abandoned.

A few comments are in order at this point:

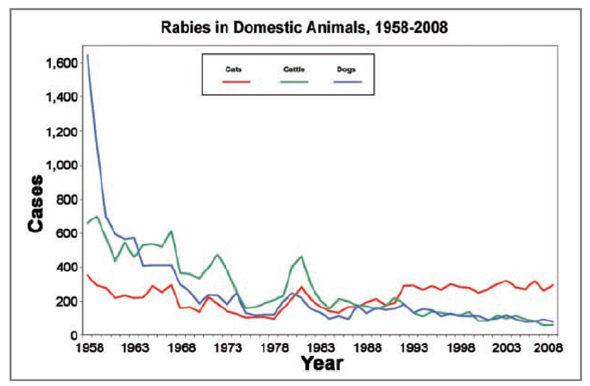

Dauphine fails to acknowledge that pets brought in to be “reunited” with their owners were taking up the shelter’s limited space, thus increasing the likelihood that cats would be killed. [2, 3]

And she never admits that any cats deemed feral—correctly or not—would almost certainly be killed. Instead, she dances around the issue, playing games with the judge magistrate, who, it’s clear, is unfamiliar with the issue (hence, she never asks what happens to the unsocialized cats brought to AAHS).

In fact, when AAHS backed out of its contract with the county a year later, it was due to “philosophical differences” concerning feral cats, according to the Athens Banner-Herald.

Keeping what is essentially a wild animal in a cage for five business days—the amount of time the county requires for any animal it picks up—is cruel and futile, because they rarely are adopted, [AAHS Executive Director Crystal] Evans said. “We would argue, for a truly feral animal, that’s inhumane,” she said. “These are cats that have had basically no human contact, so basically what you’re doing is scaring them to death for seven days and then killing them.” [2]

There’s an irony to all of this.

I’m told by people familiar with the situation that AAHS’s decision to cancel its contract was, in fact, largely the result of Dauphine’s “community service” activities. She had broken the system. And once AAHS canceled its contract, there was no place to take feral cats—a predicament that the Athens-Clarke Commission resolved, in 2010, by voting 9–1 in favor of TNR. [4]

In other words, Athens’ decision to adopt TNR, which Dauphine herself describes as “a resounding defeat for science—and for wildlife conservation,” [5] got a major push from one of its harshest critics.

As it happens, Dauphine was interviewed for the 2009 Banner-Herald story, arguing, “There’s very little or, arguably, no evidence at all that [TNR is] effective. To me, it’s just a lot about people’s discomfort with death and people not wanting to deal with it.”

Was Dauphine suggesting that she has no such qualms?

Dauphine’s Testimony II

Dauphine wrapped up her testimony by explaining her rationale for trapping the defendant’s cat. (She never explains how long she had the cat; nor does she deny having the cat for 16 days.)

…my friends in the Cambridge Apartments were telling me that it was not the first time that cat was lost. Apparently it happened again, so the cat—there is a leash law in Athens and it applies to all domestic animals.

So all domestic animals are supposed to be under their owner’s control at all times. A lot of people don’t pay attention to that with cats. With dogs—obviously if your dog is running around the Animal Control will pick it up, but this is what they can’t do with cats because they don’t have the manpower.

But some—my friends at Cambridge told me that there have been a number of missing lost cat signs, and that particular cat that the website was about was lost again about a month later…

(I’ve spoken with the defense witness, and he tells me that the cat did not go missing again—and that this is just one part of Dauphine’s testimony that “doesn’t compute.”)

JM: Okay. And so you want me to arrest […] on a good behavior bond because you fear for your safety?

ND: I was told by the Humane Society that this person was going to come and physically hurt me, or that they were talking about it. And also on the websites that they were posting on they said that people were following me or they had people following me. They’re kind of vague. They’re not explicit threats but—

JM: But I have to arrest based on your fear of […], not based on what other people might do.

ND: Right, right.

JM: So tell me why you’re fearful of […]

ND: Well, I don’t know her, but she seems to be obsessed with looking up information about me, with contacting people about me. She created an entire website about—that I’m supposedly evil, and all of these crimes that I’ve supposedly committed, when I have absolutely no relationship with her at all. And when I spoke to the police about it, he said that this pattern of behavior makes him worried that she might come and do something to me, so he advised me to get them to leave me alone.

JM: You didn’t have your lawyer contact her, or anybody contact her? Did the police contact her?

ND: I talked to an officer that said he would have his partner talk with her, but I don’t—

JM: Did you get the result of that?

ND: I wasn’t able—I tried to follow up with the police and I wasn’t able to get a communication from them. I did have—I did speak to a lawyer about a defamation case and he—

JM: That’s civil though.

ND: That’s right, yes, so that’s a separate case—so the lawyer contacted them about the website or about the civil case but not—I did talk to several police officers, and they both advised me to file the bond—the good behavior bond—to keep her from continuing to threaten me.

So I don’t know. It’s hard for me to know because I don’t—I don’t scare easily but I find it very disturbing that somebody is working this hard to create a lot of negative propaganda about me.

JM: Has anything happened since May or April?

ND: Since May—since May 18, I’m not aware of anything further.

JM: Anything else you want to tell me?

ND: Not unless you have questions.

JM: [Addressing the defendant]… Do you have any questions you want to ask her?

Defendant: Did the person on the phone with the Athens Area Humane Society identify themselves?

ND: It was […] the Director who called me…

Defendant: The person [who] made threats indirectly to you to—did they identify themselves on the phone?

ND: The Director of the Humane Society called me… The Assistant Director… took the call, and she told me details about this person.

JM: Did she give the person’s name is the question.

ND: She did not give the name.

Defendant: Who took the call again?

ND: […]

JM: Any other questions?

Defendant: No, ma’am.

Two individuals testified on behalf of Dauphine, essentially agreeing with her account of the telephone call she received from AAHS informing her that the defendant (whose name was withheld) was quite angry with Dauphine.

The Defense

A single witness testified on behalf of the defendant.

Defense Witness: On March 31, 2008 our cat went missing. He was gone for a couple of hours. We went outside looking for him and—there’s a forest around our apartment complex owned by some different properties—and in the course of looking for him we noticed some traps that were set for cats—with cat food in them—in the forest.

And, you know, silly us, being naïve and not knowing that there were people that did this out there, we thought it was a humane organization and that probably our cat—he loves wet food—probably got trapped by these people. So we put some notes on the cages saying, “If you have our cat, please call us back,” and we went to dinner.

We came back about an hour later and, lo and behold, the traps were gone and we never got a phone call from these people whatsoever and, in fact, I had noticed when I was looking at the traps that there’s no identifying markers on the traps at all either. So I started calling around the humane organizations around town that are responsible for trapping cats. We talked to all of them. Every one of them said—we called these different organizations and they—all of them say, No, all of our traps have signs on them, have labels on them, and we haven’t been trapping at your apartment complex. So this is the first time that we really start to get suspicious like, Whoa, something’s happening here, you know, What’s going on?

So we go to the Athens Area Humane Society—well, we put up signs everywhere. We go to the Athens Area Humane Society and they tell us, you know, that there’s what they described as a crazy lady who has been trapping cats for about three years here in Athens, including people’s pets. That was their words, not my words, and, you know, we’re shocked at this.

Actually a couple of nights before, we had been looking online—like, who traps cats illegally in town, and we had read that maybe it was dog catchers. So we spent all night bawling, thinking our cat had met this horrible death, but when we find out that it’s this woman that eventually turns them in to the Humane Society, we were encouraged—but we wanted to get our cat back as quickly as possible because at this point it had been over a week.

And finally about, you know, through the course of this time, some people at the Humane Society and friends of theirs were—they wouldn’t tell us who the person was because of confidentiality reasons—but started telling us some information about where that this person had been trapping. So what we started to do was go to the Wal-Mart parking lot which was one of the places and—that they told us—and the Carmike Theater parking lot, and hoped to catch this person in the act and get some pictures of it so we could prove that she was criminally trespassing, and that—and then maybe we could force her to give our cat back.

… we also had a person […] who was helping us do this, who was also staying at some of these—in some of these parking lots—helping to catch the person. Well, lo and behold, 16 days after our cat is gone, Nico turns in our cat to the Athens Area Humane Society—surprise, surprise, it was trapped.

JM: How do you know Nico does that?

DW: Because we were—well the Humane Society takes the names when she turns them in and I also saw her there when—

JM: You saw her there with your cat?

DW: Yes, well […] was staking out the Humane Society and saw her turn in my cat, and when I got there, she was—Nico was there filling out the paperwork for the cats that she had turned in, and I got my cat back immediately and they said, “Yes, he had just been turned in.”

She claimed that—Nico claimed that she caught him five days prior at Tivoli Apartments. So basically there’s one of two explanations here. One: she caught—our cat wandered for 10 days across multiple, and busy, streets—this cat that hardly ever goes outside—and happened to get caught by the person that we were looking for.

Or, the person knew we were onto them, knew they were trespassing—we have signed statements from both the YWCA and the Cambridge Apartments where we found the traps that she—they have never allowed someone to trap there—knew that they were trespassing, and so freaked out, and kept the cat and didn’t call us. It just, to me, makes sense that she had our cat for 16 days. Either way, she caught our cat.

…We’ve never made any violent, physical threats to her. I contacted the police and asked them if there was enough of a case to get her on trespassing, et cetera, and they said there’s probably not enough for a criminal case but you have a pretty strong civil case.

They said also one of the officers offered to go over to her house and offer her a warning on criminal trespass, which he told me he did, and he said that Nico said, “I’m sorry, and I promise I won’t be trespassing,” or whatever.

JM: Do you know anything about [the blog]?

DW: Yes, we helped form the blog. The blog is just an account of everything that I have told you here today.

JM: That’s not very nice. Why would y’all do something like that?

DW: Because we think there’s a public right to know that this person—we learned from the Humane Society this person has been trapping people’s pets for three years, many of which get euthanized because she dumps so many off at the Humane Society.

JM: So you think that’s okay to—

DW: I think the public has a right to know that she’s been doing this.

JM: So you think that that’s okay to say that she’s an evil person by putting this on here?

DW: Well, the evil is hyperbole, but everything else on there is our story, is exactly what happened.

JM: You think it’s okay to do this?

DW: Yeah, I think it’s public right to know. I think it’s called freedom of speech, and this is not a libel case.

JM: It’s almost like everybody gets to decide what their own rights are. She gets to decide she has the right to decide that she’s an evil person, and y’all just publicly display the things that y’all just—

DW: Well, this is not a libel case.

JM: Don’t talk when I talk.

DW: I’m sorry.

JM: Okay, because I’m mad at both sides. This is kind of ridiculous—

DW: It is.

JM: —to waste my time with her picking up cats, and y’all saying that she took your cat. It’s kind of crazy, and I just don’t understand why people think they have the right to just make up their own rules. You get the right to say she’s evil; she gets the right to take cats. It’s kind of crazy to me.

DW: Well yeah, I mean, the evil thing may be—admittedly—is a little exaggerated, but if you read the rest of the blog everything else is exactly what I’ve just said, and I do think that, like you said, there is a reason why what she’s doing would make people mad. I mean, our cat was gone for 16 days.

We cried about it. When we got him back, by the way, he had five days worth of fecal matter impacted in his intestines. We have the veterinary bill. We had to take him to the vet to have the fecal matter removed from his intestines. It was one of the most horrific experiences of my life, where I had to dig poop out of my cat because he had been trapped in a cage for 16 days because of this woman and now we’re the ones on trial?

I mean we’ve contacted lawyers, we contacted the police, we have done this legally and professionally at every step of the way, and now suddenly we’re the ones on trial? This is ridiculous. I can’t—

JM: So did […] call the Humane Society and threaten Ms. Dauphine? Do you know?

DW: I have no idea—no, I don’t think so.

JM: That’s why you’re here, because the Humane Society said someone threatened her.

DW: When we talked to the Humane Society we didn’t know her name at all. So this is—

JM: So how did you find out her name? From […]?

DW: No, we found out her name when she turned in our cat.

JM: Okay. So you don’t know who threatened her?

DW: No, and we didn’t know her name, so if […] did make a threat before when we talked to the Humane Society people, she was threatening a generic person who trapped our cat, not Nico specifically.

JM: Well somehow somebody found where Ms. Nico lived based on her address from somebody […] Do you know anything about that?

DW: No, no, no, no. That’s not true at all. We found out how she lived because I followed her home the day she turned in my cat.

JM: You followed her home? You think that’s okay.

DW: I think when we’re trying to gather evidence for a criminal case about her trespassing.

JM: That’s what the police are for.

DW: The police said we—actually the police officer encouraged me to—he said trespassing, you have to catch them in the act, and he encouraged me to follow her and to try to catch them in the act of doing this and trespassing.

After a short break, the judge magistrate returned with her decision.

JM: …I was leaning toward arresting both of you, because I think there is a reason why the law allows police officers to do certain things that the public is prohibited from doing. Ms. Dauphine, I think your cause is admirable, but I also think it’s dangerous. I don’t think you have the right to go onto other people’s property to trap animals because there is no public service to do that.

Now the [defense] witness […] testified to three agencies that he knew that did what you do on your own, and that they seem to have some protocol for doing that. I don’t know if that’s true or not, and I really—to be honest with you—don’t really care, but what I do know is that if you try to do something on your own that involves other people’s property you get yourself in trouble for doing that, either civilly because you took their animal without consent or criminally because you trespassed on somebody else’s property in order to do what you think is your mission to do.

So I’m not saying that it’s not a worthy cause, and that it shouldn’t be done—because I don’t care that much for stray animals either—but I think you’ve put yourself in a very difficult position by doing something like that, so I’m not going to arrest you for it, but I just think you need to think about what you’re doing and how you potentially get yourself in trouble for doing it.

On the other hand [Defendant], you’re not innocent in all this either. Just because someone does something that you think is wrong, in terms of taking your animal, you don’t have the right to be a vigilante any more than she does.

You don’t have the right to have […] stalk her, or follow her to find out where she lives, or who she is. You don’t have the right to put evil things on the Internet just because you feel like she does things wrong.

There are proper procedures for that. You could have brought her in this proceeding, just like she brought you, to say to me, Stop her from doing this; I think that’s wrong—she’s trespassing on people’s property, she’s taking animals that doesn’t belong to her.

I can stop her. The law doesn’t give you the right to take matters into your own hands and stop her from doing something that she thinks is wrong. So my policy has always been if you both are wrong, and I find legally that you both did what was wrong in the eyes of the law, that I either arrest both of you or I arrest neither one of you.

And I don’t think justice will be served by arresting both of you, so I’m not going to arrest either one of you. But I’m going to warn you as well that this is not the proper way to handle something as a citizen… to make evil comments about people on the Internet just because they did something you don’t like.

There is an application for arrest warrant procedure—you fill out the application, you bring her here, and let me fuss at her or let me arrest her, because you don’t take matters into your own hands… I don’t think that’s the proper way to handle it.

If the police told you that […] should follow her to find out where she lives, you send that police officer to me and I’ll chastise him, because that’s not the proper way to handle proceedings—to follow her to find out where she lives so that you can do whatever you think you ought to be able to do.

So, still, I’m mad at both of you all but I’m going send you on your way…

Civic Duty

Three months after her court appearance—with the TNR debate heating up in Athens—Dauphine weighed in publicly, writing a letter to the editor of Flagpole, Athens’ alternative weekly newspaper.

In it, she touches on all the usual talking points (e.g., cats are non-native, exaggerated predation rates, etc.), and portrays her trapping as a civic duty—done in the best interest not only of the community, but also of the cats. Dauphine also suggests—contrary to what she admitted in court—that her trapping efforts were limited to her own property.

“After reflecting on my responsibilities as a citizen and learning the relevant laws, I began trapping what turned out to be dozens of cats on my property. The vast majority were feral and stray and some of them were suffering from infectious diseases…

I’m all for enjoyment and finding a sense of purpose, but I think we can agree that we all need to do that without infringing on everyone else’s rights and causing mass destruction. If helping feral cats is your thing, that’s great—go out feed them and care for them to your heart’s content in your own house or an enclosure on your own property, where they will be safe from harm and will also not harm other animals or people…

It’s a free country, as the saying goes, but we are also a nation of laws. I do not have the freedom to release dogs, horses, goats, cattle, snakes, tigers or bears on my neighbors’ property. Likewise, I don’t want other people releasing animals, including cats, feral or otherwise, on mine. Cats are beautiful animals that make wonderful pets, but they were domesticated thousands of years ago—they’re not wild, they don’t belong outside roaming and killing native wildlife, and your cats definitely don’t belong on my property…” [6]

In what can only be described as gross hypocrisy, Dauphine closes her letter by arguing that “TNR is not respectful of law, private property, or citizens’ rights.” [6] Had she been more respectful of the law, private property, and citizens’ rights, Dauphine wouldn’t have found herself in court three months earlier.

Or—if the Washington Humane Society investigators are right—once again, three years later.

Literature Cited

1. Johnson, J. (2008, February 2). Man who abandoned cats to serve 20 days. Athens Banner-Herald (GA),

2. Aued, B. (2009, March 28). Feral feline problem now life-or-death issue. Athens Banner-Herald, from http://onlineathens.com/stories/032809/new_415448061.shtml

3. Aued, B. (2009, Auguest 3). Athens Area Humane Society moves to new digs in Watkinsville. Athens Banner-Herald, from http://onlineathens.com/stories/080409/new_475853412.shtml

4. Aued, B. (2010, March 3). TNR approved in 9-1 vote. Athens Banner-Herald, from http://www.onlineathens.com/stories/030310/new_569880708.shtml

5. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., “Pick One: Outdoor Cats or Conservation.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 50–56.

6. Dauphine, N. (2008, October 15). Letter to the Editor. Flagpole, from http://flagpole.com/Weekly/Letters/FeralCats.15Oct08

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under fire for proposed roundups of free-roaming cats in the Florida Keys, an out-of-control burn on National Key Deer Refuge land, and participation in anti-TNR workshop.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under fire for proposed roundups of free-roaming cats in the Florida Keys, an out-of-control burn on National Key Deer Refuge land, and participation in anti-TNR workshop.  Today would have been my mother’s 83rd birthday.

Today would have been my mother’s 83rd birthday.

Northern mockingbird. Photo courtesy of

Northern mockingbird. Photo courtesy of

On Tuesday,

On Tuesday,