On June 25, 2002—nine years ago tomorrow—Akron, Ohio’s Ordinance 332-2002 went into effect.

The “cat ordinance,” as it’s typically called in newspaper accounts, made it illegal for cats to be “off the premises of the owner and not under restraint by leash, cord, wire, strap, chain, or similar device or fence or secure enclosure adequate to contain the animal.” In addition, it became the duty of Akron’s Animal Control Wardens to “apprehend” and “impound” any cats “running at large.”

Enacting such a law in a city of around 215,000 people, spread out over 62 square miles, would seem to be a labor-intensive—and therefore costly—undertaking. But according to the latest TNR “Fact Sheet” (updated in February) from The Wildlife Society (PDF), Akron’s roundup was a real bargain:

“Managed cat colonies are often claimed to be the cheapest form of control for areas with feral cats. In Akron, Ohio, nearly 2,500 cats were trapped from public parks. Of these, approximately 500 were adopted while the remaining 2,000 feral, diseased, or injured cats were euthanized. The entire project cost less than $27,000. At the costs paid by Maddie’s Fund in California ($50/neuter, $70/spay), sterilizing just 500 cats would cost approximately $30,000, in addition to the costs of trapping, euthanasia for the sick or injured, and subsequent feeding of all the rest.” [1]

As its source, TWS cites a 2004 paper (presented as part of the American Veterinary Medical Association’s 2003 Animal Welfare Forum, “Management of Abandoned and Feral Cats”) by Linda Winter, founding director of the American Bird Conservancy’s Cats Indoors! campaign. But Winter makes no mention of public parks:

“Advocates of TNR believe that the general public does not support large-scale trap and remove programs and that they are cost-prohibitive. However, in response to complaints from citizens about numerous stray and feral cats, the Akron City Council passed an ordinance on March 25, 2002, prohibiting domestic cats from running at large. As of August 31, 2003, a total of 2,495 stray and feral cats had been trapped by citizens as well as by 4 wardens on an on-call basis and taken to Summit County Animal Control. Of those cats, 530 were redeemed or adopted and 1,965 were euthanatized because they were feral, injured, or diseased. The cost to the City of Akron was $26,546. If the public did not support this program, far fewer cats would have been trapped because private citizens did most of the trapping.” [2]

Whereas Winter emphasizes the apparent community support for Akron’s cat ordinance, TWS is more interested in playing the public-health-threat card—untroubled, it seems, with a bit of revisionist history in their “fact sheet.” I’ve pored over dozens of newspaper stories in the past weeks—spending what Michael Hutchins would likely consider an “inordinate amount of time”—and I’ve found no references to cats being trapped in public parks anywhere in Summit County.

Still, there’s an interesting story here—beginning with Winter’s source: “James G, Summit County Animal Control, Akron, Ohio: Personal communication, 2003.” [2]

At the time Winter spoke with Glenn James, he held the director’s job at SCAC. In January, 2004, James was fired for a host of problems at the shelter he oversaw. Among them: “widespread use of correction fluid to alter euthanasia logs,” and “a record-keeping system so poor that it’s impossible to determine what happened to dozens of animals.” [3]

It was, it turns out, also impossible to tell what happened to the shelter’s supply of Fatal-Plus, a drug used for euthanasia. (“James eventually pleaded guilty to a single felony charge of illegally processing drug documents after the prosecution determined that, while he did not steal any drugs from the shelter, he knew that they were being taken and did nothing about it.” [4])

All of which raises serious questions about the figures James reported to Winter. One also wonders about the extent to which initial support for the cat ordinance was dependent upon a blissful ignorance of the conditions at SCAC—especially those affecting animal care.

And yet, years later, TWS is suggesting that Akron’s cat ordinance is a model for budget-conscious municipalities across the country. In fact, Akron’s free-roaming cats policy was far more costly than TWS would have us believe, and far less popular than Winter suggests.

It also contributed significantly to the inhumane treatment of animals—cats and dogs alike—brought to the SCAC facility.

True Costs

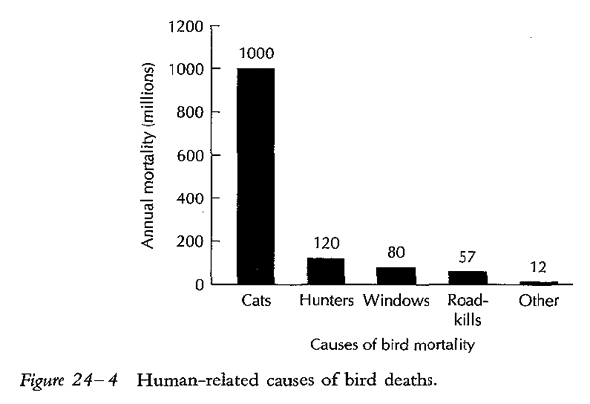

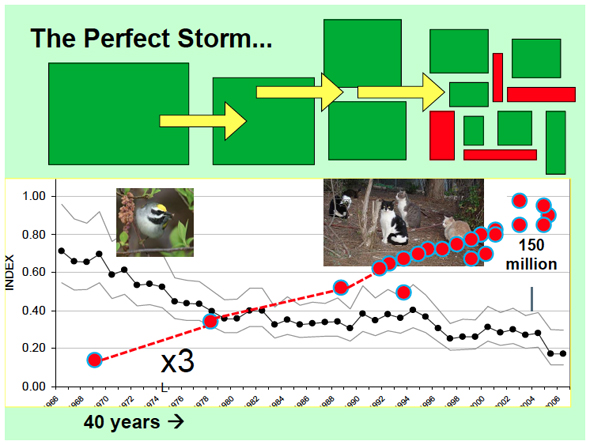

Comparing the costs of traditional trap-and-kill programs to those associated with TNR is no trivial undertaking. And, as Cornell’s David Pimentel has clearly demonstrated, attempts to account for the environmental impact of feral cat management can quickly devolve into the absurd.

That said, we need to start someplace.

According to Winter/TWS, Akron taxpayers spent approximately $13.50 for each cat euthanized killed—the only ones guaranteed not to reproduce. (As recently as 2006, Summit County didn’t require sterilization of cats redeemed or adopted. [5]) That’s roughly one-fifth of what TWS claims Maddie’s Fund pays for spay/neuter services (described in David Jessup’s 2004 paper [6]).

It’s not clear how James arrived at $26,546, though a similar estimate was reported in a January 2003 story in the Akron Beacon Journal. [7] Comparing 2002 and 2003 Summit County budget documents, SCAC’s “Charges for Services” actually declined slightly from 2002 to 2003. Interestingly, the year-to-year difference in “Total Animal Control” numbers ($26,756) matches almost perfectly James’ figure—but that may be merely a coincidence.

In any event, if TNR were truly five times as costly as Akron’s roundup, one would expect communities all over the country to stick to “traditional” methods of feral cat management.

But, as Mark Kumpf, former president of the National Animal Control Association (NACA) points out, “there’s no department that I’m aware of that has enough money in their budget to simply practice the old capture-and-euthanize policy; nature just keeps having more kittens.” Traditional control methods, argues Kumpf, are akin to “bailing the ocean with a thimble.” [8]

And, contrary to what TWS suggests, bailing the ocean with a thimble isn’t cheap.

Shared Expenses

According to a 2005 report from the Ohio Auditor of State, 21 municipalities—including Akron—“save on overhead costs on employee salaries and benefits, maintaining a fleet of vehicles, and the boarding of animals” by contracting with SCAC. [9] Summit County was saving too, by contracting with the Humane Society of Greater Akron for veterinary and after-hours/emergency response services.

So, even if Akron did pay only $13.50 per cat, it was largely because of the extensive costs absorbed by the 540,000 or so residents of Summit County. But it didn’t take long for Akron to overwhelm County resources.

Summit County’s 2003 Budget report (PDF) includes what appears to be a request for four additional pound-keepers, which would have doubled the staff caring for animals at the shelter. Other information in the same report, however, indicates that SCAC staffing would remain at 2002 levels—suggesting that perhaps the request was more of a political statement than anything else.

Justification for the additional pound-keepers (“responsible for the daily care of all animals brought to the Animal Shelter” as well as “the care and maintenance of the Animal Control facility” [10]) includes what sounds like a perennial complaint: a growing population leading to more “animal problems.” [10] But did the population of Summit County double between 2002 and 2003? Hardly.

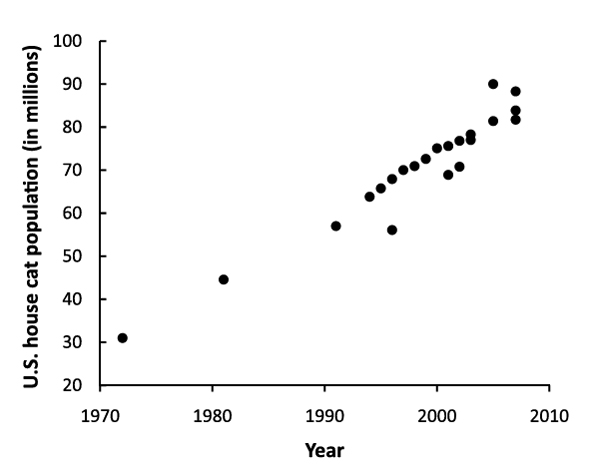

A quick check of Wikipedia suggests a 5.4 percent increase from 1990 to 2000, after which it remained flat or even declined slightly. (U.S. Census data: 1980: 524,472; 1990: 514,990; 2000: 542,899: 2010: 541,781.)

So what did change?

“…the City of Akron recently passed a new cat control ordinance, which has created more work for the pound keepers due to the substantial numbers of cats being impounded. To keep up with the escalating problems it will be necessary to hire more staff to maintain the same level of service that is currently being provided. Furthermore, additional supplies and equipment will be needed to accommodate the additional animals being impounded. More revenue will be needed to cover these expenses.” [10]

The Cattery

If the shelter didn’t receive additional help, it at least got a little larger.

In 2002, the facility’s lobby was partitioned to accommodate an 18-by-10 “cattery,” completed just in time for implementation of 332-2002. Cost of the renovation, which James called a “small project,” was $80,000. [11]

“Our decision to build the cattery,” James told the Beacon Journal, “came before plans for the ordinance.” [12] Fair enough—newspaper accounts indicate that James first floated the idea in 1998, a year after Akron considered licensing cats. “We want to be prepared when the time comes that we have to control cats more stringently. It’s just good common sense. Every animal control facility should have a cattery.” [13]

Still, it’s doubtful that Akron’s city council would have voted in favor of the cat ordinance had the cattery not been in the works. Indeed, they had scrapped the cat licensing proposal for this very reason (“the city decided not to because its animal shelters would have had to keep cats for three days before disposing of them, and they didn’t have the room”). [14]

The cattery increased Summit County’s capacity from four cages to 24, with 12 more in the “overflow room” [15] (though James told the Beacon Journal, “We could hold up to a maximum of 50 cats at one time”). [12]

A NACA study team, summoned by Summit County to review conditions and practices at SCAC, were unimpressed. Among the 132 recommendations included in their 2004 report: “Summit County should explore the possibility of constructing a new animal sheltering facility within the very near future” [15] (the emphasis is theirs, not mine). Indeed, the facility was awarded NACA’s lowest rating: 1 (“an immediate need”).

Cost of Living Dying Increase

As part of their deal with Akron, SCAC agreed to hold cats for five days: “three days to give the owners time [sic] retrieve them and another two days for adoption purposes.” [16] Akron was to pay $5 per day for the “mandatory three-day stay and the $10 disposal fee, if need be.” [16] (In fact, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that many cats and kittens were killed long before their time was up.)

But Akron’s cat ordinance quickly became a victim of its own “success,” with about 900 cats “plucked from city streets” [17] in the first three months alone.

Intake numbers for previous years vary considerably. In 1999, for example, James told the Beacon Journal “At least 200 stray cats each year are trapped by residents and brought to the Summit County Animal Shelter.” [18] In 2002, six weeks prior to the cat ordinance going into effect, the paper reported (again, citing James) that 400 cats “wind up at the county shelter each year.” [11] Then, in another story just seven months later, the figure was 3,500. [19]

Two years later, in a 2004 op-ed, the Beacon Journal suggested “100 or so had been the norm.” [20]

Whatever the numbers were, it’s clear that the increase overwhelmed available resources. So, in 2004, the County proposed rate increases for its animal services, “largely,” as Beacon Journal reporter Lisa A. Abraham put it, “because of the crush of stray cats the city has been depositing at the shelter.” [21] The cost to house a cat doubled, as did the fee for putting a cat down. (The increased “business” affected dogs, too: their housing fees also increased from $5 to $10 per day, while the cost to put a dog down tripled to $30.)

Additional Expenses

In addition, numerous ancillary expenses were incurred in response to 332-2002.

The NACA reviews, for instance—one in 2004, and a follow-up in 2006—were, it seems clear, a response to extensive criticism of shelter conditions, policies, and practices by local groups opposed to the cat ordinance. [22, 23] The cost: $8,000. [24]

In 2003, Summit County committed about $15,000 “to install cameras and other security equipment at the county animal shelter.” [25]

“The move is part of increased scrutiny of the shelter, which has come under fire from animal activists who allege that inhumane treatment of animals and criminal behavior have gone on at the North Street facility.” [25]

The following year, Akron’s city council approved $16,000 to microchip 1,000 cats, and “conduct some low-cost spaying and neutering clinics around the city.” [26]

“The move came in response to the furor that was created after the council passed a law two years ago, allowing free-roaming cats to be picked up if someone complained.” [26]

Akron had purchased five microchip scanners in 2002, but, as customer service administrator John Hoffman told the Beacon Journal two years later, “ha[d] yet to scan a chip.” [27] (Estimated cost: $1,500.)

It’s not clear how much sterilization was done (or how many residents took advantage of the microchip offer, for that matter). In fact, Hoffman was forced to defend what some saw as misplaced priorities (clearly, such efforts are aimed at pets and not feral cats):

“What I’ve heard is that some groups prefer us to spend our money doing neutering, and that’s something we’re considering that will come later… But I don’t follow the objections There’s no harm, no foul. And at $10, it’s affordable, so I cannot imagine a legitimate reason not to do this.” [26]

Eradication at Any Cost

Suddenly, Maddie’s sixty-bucks-a-cat is starting to look like the real bargain.

Not that I’m prepared to assign an exact number to the per-cat cost of Akron’s cat ordinance—sure to be a painful, unproductive exercise in “Pimentelian economics.” Still, though, it’s easy to imagine the true cost of 332-2002 being comparable to—or even exceeding—the costs of TNR.

When it comes right down to it, though, I think the real attraction for TWS is not the (fictitious) price tag of Akron’s cat ordinance, but its incompatibility with feral cats in general and TNR in particular. In the community, Akron’s unsocialized cats are at great risk; in the hands of SCAC, they’re sure to be killed.

Community Support

Winter’s measure of community support—the number cats trapped by Akron residents—is, given the vast discrepancies in reporting, likely to be inaccurate. Even at its most accurate, though, such a measure is remarkably incomplete.

Legal Opposition

Winter never mentions the controversy surrounding the City Council’s vote on 332-2002, for example. Just days before its implementation, the council—“faced with the looming threat of a lawsuit”—repealed the original ordinance. [16]

“Immediately afterward, the council unanimously passed a nearly identical version of the law as an emergency measure. It went into effect immediately as Mayor Don Plusquellic signed it following the meeting… City officials say this version should withstand legal scrutiny if a group of cat fanciers—Citizens for Humane Animal Practices, or CHAP—makes good on its threat of a lawsuit.” [16]

Earlier that evening, CHAP members held a candlelight vigil and protest.

“The group—sporting placards saying things like “Save our cats” and “I can’t speak at city council,” wearing shirts with the slogan, “No tax $ for cat killing” and carrying plush toy cats—has a lawsuit prepared and ready to file, according to… the group’s attorney. [16]

Although CHAP’s request for a preliminary injunction was denied in late 2002, the judge hearing the case acknowledged the risk of “irreparable harm” posed by Akron’s cat ordinance:

“‘Due to the lack of guidelines and/or policies, it is possible for cats to be euthanized’ without their owner or owners ever receiving proper notification, she wrote. If a cat owner never receives notification—and that individual’s pet is picked up and ultimately destroyed—the owners are indeed ‘irreparably injured/harmed,’ she said.” [28]

For “owners” of feral and stray cats, of course, there was never any proper notification.

General Opposition

Letters to the Beacon Journal’s editor seem to fall almost exclusively in the opposition camp (though, to be fair, I did not do a rigorous comparison).

Brenda Graham’s January 31, 2003, letter (one of at least two she had published in the Beacon Journal) compared the “the slaughter of healthy cats and kittens” brought on by 332-2002 to “the Salem witch hunts of the 17th century. Both are founded in ignorance and spite.” [29] Even so, Graham remained optimistic about her community: “We can turn this around and showcase Akron as compassionate and progressive, not barbaric.” [29]

“Why does the city use our tax dollars wastefully on a process that is both ineffective and cruel?” asked Patricia Shaw in her July 13, 2003, letter. “Why can’t Akron’s animal-control policies be brought into the 21st century?” [30]

“Many major cities have determined that euthanasia does not solve the problem of animal overpopulation. There is too much information out there for Akron City Council to be still operating in the Dark Ages. If others have found a better way, why can’t Akron do the same? I can’t imagine that these cities’ councils have a corner on intelligence.” [30]

Shaw’s vocal opposition to SCAC’s policies made her the subject of retaliation, resulting in the killing of dozen of cats and kittens for which she’d agreed to find homes (see below).

How closely these examples reflect opinions throughout the community is anybody’s guess. They may well represent a small minority—however vocal. On the other hand, I haven’t seen a single mention of a public discussion of 332-2002 among the dozens of Beacon Journal stories I’ve read on the topic—it seems there was very little public input on either side of the issue.

Finally, there’s the issue of effectiveness. No doubt supporters of the cat ordinance figured that killing 2,000 or so cats each year would make a difference in the number of stray and feral cats. If you’re determined to bail the ocean with a thimble, I don’t suppose it makes much difference that you’re 500 miles away.

Animal Services/Care

Economics and politics aside, it’s important to consider how cats were treated in the aftermath of 332-2002 (a factor TWS and Winter conveniently overlook). Akron’s cat ordinance, it’s clear, exacerbated a number of problems within SCAC, and created plenty of new ones. And, as is often the case, the animals suffered tremendously as a result.

A History of Abuses

I’ve been unable to determine precisely when Glenn James joined SCAC (the earliest newspaper story in which his name appears is dated June 1989), but it’s clear that he inherited a profoundly dysfunctional organization.

“For the most part—and especially in years past,” writes Beacon Journal reporter Charlene Nevada in her 1991 profile of James, “the people who chase dogs in Summit County have found themselves on the payroll because of political friends.” [31]

“James was hired and promoted because it became obvious to those around him that this was someone who walks on two feet but understands those who walk on four.” [31]

Maybe so, but it seems there wasn’t much competition, either.

Dog warden Joseph Kissel, who took over in the fall of 1988, had been on the job just two weeks when news that his wife had for years been selling cats—obtained free from the shelter—for $25 to $30 apiece to research facilities, including the Northeast Ohio Universities College of Medicine. [32]

“Kissel said his wife was treated like anyone else. Anyone can get as many cats as are available for free, he said. ‘Anybody who walks off the street. Can I have a cat? Yeah. Can I have 10 cats? Yeah. Can I have all of them? Yeah,’ Kissel said. He refused to discuss his wife’s business in detail, saying it was her business, not his. Kissel declined to estimate how many cats were released by the pound each year for sale to medical research organizations or how many his wife had received.” [32]

By 1991, with James in charge, SCAC had cut out the middleman, “illegally selling dogs from its animal shelter to research facilities for $27 over the state-imposed price,” bringing in perhaps as much as $16,000 in pound seizure fees. [33]

James defended the price gouging, citing “escalating animal-control expenses.” [33]

Akron’s Cats

The first four days under 332-2002 were a harbinger of grim days to come. Of the 53 cats brought into the shelter, “43 were too sickly to be kept and were euthanized.” [34]

“The sick cats were found to have ringworm, upper respiratory infections or were severely flea infested. Most were malnourished and appeared to be feral—wild cats that aren’t used to human contact… Some were kittens who hadn’t been weaned from their mother and wouldn’t survive…” [34]

For Akron’s cats, a runny nose had become fatal. Deadly, too, was a feral appearance—whatever that means.

And still, Hoffman told the Beacon Journal—presumably with a straight face—“We are not killing cats.”

“If there is any kind of ID tag, we’re calling that phone number and giving that cat a ride home,” Hoffman said. “If no cat goes to the animal shelter, that’s fine. We’re hoping to keep people’s pets safe and only deal with the true problem.” [34]

The “true problem,” though, was the number of cats being killed. In fact, the 81 percent kill rate demonstrated during the first four days was nothing new for Summit County; in 1988, Kissel told the Beacon Journal that 90–95 percent of the 3,000–4,000 cats brought into the shelter each year were killed. [32] (The fact that Kissel couldn’t narrow down the number of intakes any further is both alarming and indicative of conditions at the facility.)

During the first six months, the kill rate tapered off to 70 percent. [7] Six months later, the rate was up to 79 percent. [2] Imagine: four out of every five cats brought to SCAC were, as Winter suggests, “feral, injured, or diseased.” [2]

Three years later, the Beacon Journal reported to a 65 percent kill rate for cats brought into the shelter during 2005 (dogs fared slightly better, with a 49 percent kill rate). [35]

How credible any of these figures are—in light of SCAC’s record-keeping problems—is unclear, of course. Still, even their best numbers are nothing to be proud of.

Systemic Problems

The NACA reviews and related media coverage exposed a laundry list of failures at SCAC. Among them:

- At the time of the original NACA review, Summit County’s shelter was open to the public only 28 hours each week (10:00–3:00 Monday–Friday; 12:00–3:00 on Saturdays), prompting the study team to comment: “current shelter hours do not favor today’s working households.” [15]

- “During peak periods of the year,” notes the 2004 NACA report, “the facility generally operates at 100 percent capacity.” [15] Yet, on weekends, two assistant pound-keepers were allocated just 11 hours between them—to care for the shelter’s animals, clean the facility [with its 120 cages], and attend to any visitors during the three hours the shelter was open to the public on Saturdays. “The shelter could remain closed on Sundays,” suggests the report, “however the facility should be cleaned and all animals should receive food, water and care.” [15] That’s right: SCAC had to be told by NACA to take care of the animals in its care on weekends.

- The drama surrounding the top job at SCAC didn’t end with James’ termination. James’ replacement, Jeffrey Wright, resigned under pressure after just a year on the job—during which time he used nearly three weeks of sick time. [36] Anthony Moore, who was appointed acting animal control manager following Wright’s departure, last only nine months, “demoted for using a diluted formula of the euthanasia drug on animals at the shelter.” (It didn’t help that Moore had drawn criticism for removing cats “from their cages with neck hooks during hours when visitors were in the facility.”) [37] Christine Congrove, who had been James’ secretary, took over in 2006, drawing fire for her lack of qualifications and experience, $61,000 starting salary, and family ties (she’s the daughter of then-councilman Dan Congrove). [37] Congrove—now Christine Fatheree—remains Animal Control Manager today.

- Not only was Summit County’s kill rate incredibly high, their methods were often inhumane. Among the alarming results of a 2003 investigation by then-County Executive James McCarthy: “cats are euthanized with needles large enough for a cow.” [3] Even more controversial was the SCAC’s practice of intracardiac injection—or heart-stick—“a procedure for euthanizing animals by using a long needle to inject drugs directly into their hearts.” [38] And a 2006 lawsuit (more tax dollars wasted) alleged that shelter staff, having used insufficient doses of Fatal-Plus, were “throwing live animals in the freezer.” [39]

- Despite apparent concerns for the number of stray and abandoned pets, sterilization was clearly not a priority for Summit County. Among NACA’s “immediate need” recommendations in 2004 was this: “any cat or dog adoption should include some form of required sterilization, preferably prior to adoption.” [15] Two years later, though, NACA reviewers reported “no progress,” using the reevaluation to emphasize once again, “The sterilization of adopted animals should be mandatory.” [5] At that time, Summit County also hadn’t implemented a low-cost spay/neuter program in the community. [40] (Today, all pets adopted from Summit County are sterilized, although it’s not clear that any community-based low-cost spay/neuter programs have been put in place.)

- Criticism of shelter practices led to retaliation against local rescue groups. [3, 41] In “House of Horrors,” Cleveland Scene reporter Aina Hunter (now at CBS News), details the horrendous treatment Patricia Shaw received as, on two separate occasions, cats and kittens she’d agreed to find homes for were killed. (James “did it to teach us a lesson,” says Shaw. “He did it to show that he has the power of life and death—not people like me.” [41]) Hunter’s reporting reveals the abuses and deteriorating morale of an organization that had come entirely off the rails. (Interestingly, about the same time Hunter was uncovering the horrors inside Summit County’s shelter, Linda Winter was discussing the apparent success of Akron’s cat ordinance with the man in charge.)

(Detailed accounts of these incidents—and many more—can be found on the St. Francis Animal Sanctuary and The National Animal Cruelty Registry Websites.)

A Long Way to Go

SCAC has made some notable improvements in recent years—the most obvious its new $2.96 million shelter, which opened its doors last August. Those doors are open more often, too (Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday: 10 am–5 pm; Wednesday: 10 am–7 pm; Saturday: 10 am–3 pm).

Adoptable animals are also showcased online. SCAC is, according to its Website, “a proud member of the Summit Animal Coalition,” made up of several local rescue groups and the Humane Society of Greater Akron.

There’s also a volunteer program. And earlier this year, the County nearly tripled its budget for veterinary care at the facility. [42]

Still, the there’s nothing listed under the Events and Programs tab, and the e-mail link for Fatheree won’t get you very far (her e-mail address is incomplete).

More worrisome, however, is the response I got when I did get through to Fatheree, asking for recent intake, redemption, adoption, and euthanasia figures:

“Good afternoon, Christine Fatheree has sent me your request for public records. These records were destroyed per our records retention schedule and no longer available. Thank you.” —Jill Hinig Skapin, Director of Communications

Some problems just can’t be fixed with a three-million-dollar shelter.

• • •

Nine years later, it’s impossible to tell if 332-2002 is “working”—at least from the information I’ve been able to gather. But, given all that’s known about efforts to eradicate cats from oceanic islands, I doubt Akron’s cat ordinance has made much of a difference at all in terms of the number of stray and feral cats.

There’s no doubt at all, though, that the roundup has been far costlier than TWS suggests in its “fact sheet.”

Then again, TWS is about as interested in facts as the American Bird Conservancy is. (Recall, for example, how much space TWS allocated for Nico Dauphine and her “facts” in their recent special issue of The Wildlife Professional.)

I’m actually well past the point of being surprised by what TWS is trying to pull here. But I am a little surprised that they would expect anybody to fall for it. Executive Director/CEO Michael Hutchins likes to brag about TWS’s “10,000+ strong membership of wildlife professionals.” I wonder: How many of those 10,000+ does Hutchins take to be such fools?

Literature Cited

1. n.a., Problems with Trap-Neuter-Release. 2011, The Wildlife Society: Bethesda, MD. (http://joomla.wildlife.org/documents/cats_tnr.pdf)

2. Winter, L., “Trap-neuter-release programs: The reality and the impacts.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1369–1376. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1369

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1369.pdf

3. Abraham, L.A. (2003, December 6). Shelter is “Sloppy”. Akron Beacon Journal.

4. Abraham, L.A. (2004, April 24). Summit-Hired Group Backs Building a New Animal Shelter. Akron Beacon Journal.

5. Mays, J.W., Summit County Animal Control: Reevaluation Report. 2006, National Animal Control Association: Kansas City, MO. p. 36. (http://www.co.summit.oh.us/pdfs/Animal%20Control%20Reevaluation%20Report%20-%20June,%202006.pdf)

6. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552312

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1377.pdf

7. Wallace, J. (2003, January 6). Akron’s Stray Cat Effort Cheaper Than Expected. Akron Beacon Journal.

8. Hettinger, J., Taking a Broader View of Cats in the Community, in Animal Sheltering. 2008. p. 8–9. http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/taking_a_broader_view_of_cats.html

http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/broader_view_of_cats.pdf

9. n.a., Local Government Consolidation Reports. n.d., Ohio Auditor of State: Columbus. http://www.auditor.state.oh.us/conferences/fiscaldistress/handouts/files/LeadingPracticesLocalGovConsolidationReports.xlsx

10. n.a., Summit County: Building On a Solid Structure: 2003 Operating Budget. 2003, Office of Executive, Summit County: Akron, OH.

11. Miller, M. (2002, May 6). Summit Cattery Opens Next Month. Akron Beacon Journal.

12. Chancellor, C. (2002, June 26). Kitty Lockup Is Ready for First Inmates. Akron Beacon Journal.

13. Biliczky, C. (1998, August 31). Stray Cats Could Get Den at Summit animal Shelter. Akron Beacon Journal.

14. Dorell, O. (1999, July 11). Rules For Cats Pose Problems In Barberton. Akron Beacon Journal.

15. Mays, J.W., Summit County Animal Control: Confidential Evaluation Report. 2004, National Animal Control Association: Kansas City, MO. p. 164. (www.co.summit.oh.us/executive/pdfs/NACA%20Report.pdf)

16. Wallace, J. (2002, June 25). No More Catting Around. Akron Beacon Journal.

17. Warsmith, S. (2002, September 25). Woman Lands In Court For Claiming Stray Cats. Akron Beacon Journal.

18. Dorell, O. (1999, June 15). Summit Looks to Rein Cats, Dogs. Akron Beacon Journal.

19. Miller, M. (2002, December 2). Shelter’s New Web Site Goes To the Dogs. Akron Beacon Journal.

20. n.a. (2004, April 26). Practical Advice—A Helpful Plan For Improving County Animal Shelter. Akron Beacon Journal, p. B3.

21. Abraham, L.A. (2004, March 21). County Seeks Hike in Animal Shelter Costs. Akron Beacon Journal.

22. Abraham, L.A. (2004, January 24). Animal Shelter Review Approved. Akron Beacon Journal.

23. Abraham, L.A. and Wallace, J. (2004, May 5). Akron Cat Law Lands On Its Feet. Akron Beacon Journal.

24. Hagelberg, K. (2006, September 19). Dog Pound Still has Problems. Akron Beacon Journal.

25. Abraham, L.A. (2003, December 11). Eye Kept On Shelter. Akron Beacon Journal.

26. Wallace, J. (2004, August 5). Microchip Gives Cats Instant ID. Akron Beacon Journal.

27. Bloom, C. (2004, July 17). Akron Chips Away at Lost-Cat Problem. Akron Beacon Journal.

28. Chancellor, C. (2002, December 10). Cat Law Injunction Is Denied. Akron Beacon Journal, p. B1.

29. Graham, B. (2003, January 31). A Better Way to Deal with Akron’s Cat Problem (Letter to the Editor). Akron Beacon Journal.

30. Shaw, P. (2003, July 13). Taxes Ought To Fund Compassion, Not Killing. Akron Beacon Journal, p. B2.

31. Nevada, C. (1991, December 26). Lion Tamer Turns Talents to Summit’s Stray Dogs. Akron Beacon Journal.

32. Oblander, T. (1988, September 25). Summit Dog Warden’s Wife Sold Cats to Labs. Akron Beacon Journal.

33. Rosenberg, A. (1994, October 5). State Says Summit Illegally Sells Dogs from Shelter. Akron Beacon Journal.

34. Wallace, J. (2002, June 29). 53 Cats Captured in 4 Days. Akron Beacon Journal.

35. Abraham, L.A. (2006, February 12). Second Look At Shelter. Akron Beacon Journal.

36. Abraham, L.A. (2005, July 13). Summit Animal Chief Resigns. Akron Beacon Journal.

37. Hagelberg, K. (2006, March 8). Animal Control Director Named. Akron Beacon Journal.

38. Abraham, L.A. (2003, December 9). Summit County Executive Stands Behind Animal Shelter. Akron Beacon Journal.

39. Hagelberg, K. (2006, November 19). Secret Deal Settles Suit With County. Akron Beacon Journal.

40. Hagelberg, K. (2006, March 9). Animal Control Director Under Fire. Akron Beacon Journal.

41. Hunter, A. (2003, October 22). House of Horrors. Cleveland Scene, from http://www.clevescene.com/cleveland/house-of-horrors/Content?oid=1484255

42. Armon, R. (2011, February 12). Veterinary Services Budget in Summit Could Nearly Triple. Akron Beacon Journal.

North American Opossum with winter coat. Photo courtesy of

North American Opossum with winter coat. Photo courtesy of