In April, Conservation Biology published a comment authored by Christopher A. Lepczyk, Nico Dauphiné, David M. Bird, Sheila Conant, Robert J. Cooper, David C. Duffy, Pamela Jo Hatley, Peter P. Marra, Elizabeth Stone, and Stanley A. Temple. In it, the authors “applaud the recent essay by Longcore et al. (2009) in raising the awareness about trap-neuter-return (TNR) to the conservation community,” [1] and puzzle at the lack of TNR opposition among the larger scientific community:

“…it may be that conservation biologists and wildlife ecologists believe the issue of feral cats has already been studied enough and that the work speaks for itself, suggesting that no further research is needed.”

In fact, “the work”—taken as a whole—is neither as rigorous nor as conclusive as Lepczyk et al. suggest. And far too much of it is plagued by exaggerations, misrepresentations, errors, and obvious bias. For the next few posts, I’m going to present a sampling of its more serious flaws, beginning with how some researchers “reinterpret” work of others to suit their own purposes.

Tell It Like It Is

Studies of cat predation frequently cite the work of William G. George, who, in 1974, published a paper documenting his meticulous observations of the hunting behavior of three cats on his southern Illinois farm. “The results,” wrote George, “established a basis for examining the possibility that cat predation may result in depleted winter populations of microtine rodents and other prey of Red-tailed Hawks, Marsh Hawks, and American Kestrels.” [2]

Thirty years later, David A. Jessup interpreted things rather differently, giving George’s work an additional—and unwarranted—degree of certainty. Gone are the doubts that George expressed—first, regarding the impact of cat predation on rodent and other prey populations; second, regarding the relationship between these populations and the raptors that feed on them. For Jessup—who offers no additional evidence—it’s all very straightforward: “Feral cats also indirectly kill native predators by removing their food base.” [3]

More recently, Guttilla and Stapp seem to prefer Jessup’s take: “Human-subsidized cats… can spill over into less densely populated wildland areas where they reduce prey for native predators (George 1974).” [4]

If any additional work has been done on the subject (surely there are more cats in the area these days; how are the voles and raptors faring?), it seems to have gone unnoticed. Instead, Jessup, Guttilla, and Stapp (and others, too, no doubt) have simply rewritten George’s conclusion to suit their own purposes. Perhaps their version makes for a better story, but it’s rather poor science.

Credit Where Little/None Is Due

When the Lancet recently retracted a 1998 paper linking vaccinations to autism in children—“research” that sparked the ongoing backlash against vaccinations—it was headline news. The move prompted this criticism from one member of the British Parliament: “The Lancet article should never have been published, and its peer review system failed. The article should now be expunged from the academic record…”

At the risk of drawing too many parallels between the two papers, I think the same can be said for Coleman and Temple’s infamous “Wisconsin Study.” (On the other hand, it does serve a useful purpose as a red flag.) Actually, as Goldstein et al. point out, Coleman and Temple’s paper was never peer-reviewed (not necessarily a deal-breaker in my book, but such publications do warrant additional scrutiny), but achieved its mythical status by being cited ad nauseam in peer-reviewed journals, as well as the mainstream media.

Does anybody actually believe the numbers suggested by Coleman and Temple? Stanley Temple (one of the co-authors of the recent anti-feral cat/TNR comment in Conservation Biology) himself admitted their published figures “aren’t actual data; that was just our projection to show how bad it might be.” [5]

I don’t think Longcore et al. [6] or the editors at Conservation Biology put much stock in the Wisconsin Study—so why continue to publish “projections” that have been so thoroughly discredited? Because doing so strengthens their case, at least among those who don’t know any better—especially people outside the scientific community, including many journalists, policy makers, judges, and the general public.

In their recent comment, Lepczyk et al. suggest that conservation biologists and wildlife ecologists “look to the evolutionary biology community” [1] for an example of how to influence policy:

“When local policies or regulations are put forth that promote the teaching of creationism or intelligent design, the evolutionary biologists have responded in force from across the nation and world.” [1]

Let’s set aside for the moment all the baggage associated with their analogy. My question is this: Is the evolutionary biology community still publishing bogus “projections” from 13 years ago? I doubt it.

Check Your Premises

In their recent paper (available for download via the American Bird Conservancy (ABC) website), Dauphiné and Cooper arrive at their absurd figure of “117–157 million free-ranging cats in the United States,” [7] in part, by way of Jessup’s “estimated 60 to 100 million feral and abandoned cats in the United States.” [3]

So where does Jessup’s figure come from? We have no idea—there’s no citation. And Jessup is no authority on the subject—having conducted no studies or reviews of studies that quantify the feral cat population. What’s more, his “estimation” is among the highest figures published. Yet this is the shaky foundation upon which Dauphiné and Cooper attempt to build their subsequent argument.

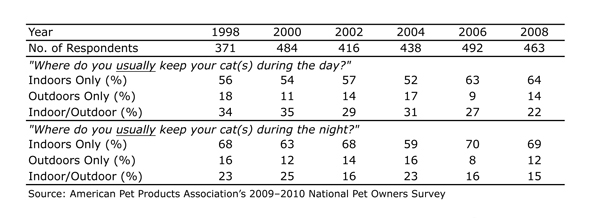

The authors then add to the (dubious) number of feral cats the proportion of pet cats allowed outdoors. They refer to a 2004 paper by Linda Winter, director of ABC’s Cats Indoors! campaign, in which it was reported, “A 1997 nationwide random telephone survey indicated that 66% of cat owners let their cats outdoors some or all of the time.” [8]

That’s an interesting way to put it—Winter makes it sound like two-thirds of pet cats are essentially outdoor cats. But the survey—commissioned by ABC!—actually indicates that “35% keep their cats indoors all of the time” and “31% keep them indoors mostly with some outside access.” [9] The difference in wording is subtle, and hampered by imprecision—it all comes down to the meaning of some.

Winter’s 2004 paper implies that there are twice as many outdoor pet cats as was indicated in the original survey—an interpretation Dauphiné and Cooper seem to embrace. Had they looked further—and to a less biased source—they might have been able to get a better handle on the degree of outdoor access. For example: a 2003 survey conducted by Clancy, Moore, and Bertone [10] revealing that nearly half of the cats with outdoor access were outside for two or fewer hours a day. And 29% were outdoors for less than an hour each day.

Do these “part-timers” have the same impact on wildlife as feral cats? Dauphiné and Cooper would have us believe they do.

[Note: For a closer look at the flaws in Dauphiné and Cooper’s paper, download “One Billion Birds,” by Laurie D. Goldstein.]

The lesson? Credible research begins with a solid foundation; a weak foundation—one plagued with unsubstantiated claims—on the other hand, leads to pseudoscience.

Or worse. ABC’s Senior Policy Advisor, Steve Holmer, cited Dauphiné and Cooper’s bogus numbers when he spoke to the Los Angeles Times about his organization’s involvement with the legal battle against TNR. It’s like the Wisconsin Study all over again.

When All Else Fails, Look It Up

Though this would seem to be utterly obvious, it apparently bears repeating: Don’t cite work you haven’t actually read.

Isn’t this emphasized in all graduate (indeed, undergraduate, too) programs? What grad student isn’t, at one time or another, tempted to take the easy way out—ride the coattails of somebody else who’s (presumably) done the real work? In addition to the ethical implications, such shortcuts tend to invite more immediate troubles, too. Again, George’s work (described above) provides an excellent case study. Below are some examples of how his work has been referenced in the cat predation literature:

“It is very unlikely that cats bring home all of the prey that they capture. What proportion they bring home has been little studied. George (1974) on a farm in Illinois USA found that three house cats, all adequately fed, brought home about 50% of the prey that they killed.” [11]

“George found that about 50% of prey were indeed brought home, with the other 50% being eaten, scavenged by other animals or simply not found.” [12]

“These approximations are probably underestimates, assuming that cats do not bring back all the prey that they kill.” [13]

Trouble is, George never said these things; what he said was:

“… the cats never ate or deposited prey where caught but instead carried it into a ‘delivery area,’ consisting of the house and lawn. The exclusive use of this delivery area was verified in 18 to 70 mammal captures per cat, as witnessed between early 1967 and 1971.” [2]

In 2000, Fitzgerald and Turner pointed out the fact that George’s work was being misrepresented, noting that the erroneous 50% figure “has been reported widely, though it is unfounded.” [14] Nevertheless, the myth persists—even in 2010.

“In Illinois, George (1974) found that only about half of animals killed by cats were provided to their owners, and in upstate New York, Kays and DeWan (2004) found that observed cat predation rates were 3.3 times higher than predation rates measured through prey returns to owners. Thus, predation rates measured through prey returns may represent one half to less than one third of what pet cats actually kill…” [7]

As Dauphiné and Cooper demonstrate, the “reinterpreted” version of George’s work makes for a very convenient multiplier—suddenly, every kill reported is doubled (or tripled, if Kays and DeWan are to be believed—and they’re not, but that’s a topic for another post). Never mind the fact that it has no basis in actual fact.

Getting a copy of George’s study isn’t difficult, especially with the inter-library loan services available today. To reference it—to use George’s work so that your own appears more credible—without ever having actually read it, is simply inexcusable. But citing it blindly suggests more than laziness—it points to a certain coziness that has no place in scientific discourse. Too much Kool-Aid drinking, and not enough honest research.

* * *

Scientists can (and do) look at identical results and come to very different conclusions. But misinterpreting, misrepresenting, or dismissing the conclusions of others, is something else altogether. As the above examples (and there are many, many more!) illustrate, this happens far too often in the feral cat/TNR literature. And if we can’t believe what researchers are saying about the work of others, why would we believe what they say about their own work?

Next, I’ll focus on some of the major flaws in the feral cat/TNR literature—beginning with small sample sizes…

References

1. Lepczyk, C.A., et al., “What Conservation Biologists Can Do to Counter Trap-Neuter-Return: Response to Longcore et al.” Conservation Biology. 2010. 24(2): p. 627-629.

2. George, W., “Domestic cats as predators and factors in winter shortages of raptor prey.” The Wilson Bulletin. 1974. 86(4): p. 384–396.

3. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383.

4. Guttilla, D.A. and Stapp, P., “Effects of sterilization on movements of feral cats at a wildland-urban interface.” Journal of Mammalogy. 2010. 91(2): p. 482-489.

5. Elliott, J., The Accused, in The Sonoma County Independent. 1994. p. 1, 10

6. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap–Neuter–Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894.

7. Dauphiné, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2010. p. 205–219

8. Winter, L., “Trap-neuter-release programs: the reality and the impacts.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1369-1376.

9. ABC, Human Attitudes and Behavior Regarding Cats. 1997, American Bird Conservancy: Washington, DC. http://www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/materials/attitude.pdf

10. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545.

11. Churcher, P.B. and Lawton, J.H., “Predation by domestic cats in an English village.” Journal of Zoology. 1987. 212(3): p. 439-455.

12. May, R.M., “Control of feline delinquency.” Nature. 1988. 332(March): p. 392-393.

13. Crooks, K.R. and Soule, M.E., “Mesopredator release and avifaunal extinctions in a fragmented system.” Nature. 1999. 400(6744): p. 563.

14. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

Using Google to translate the

Using Google to translate the