As I continue to drill down into the “The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States”—tracking down and reading journal articles, compiling the data therein, etc.—I’m finding (not surprisingly) additional holes in the various claims made by Scott Loss, Tom Will, and Peter Marra. For example:

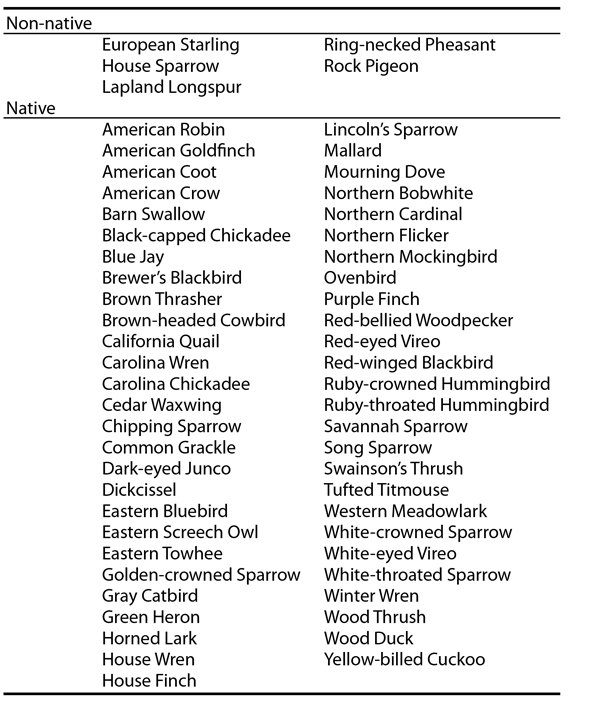

“Native species make up the majority of the birds preyed upon by cats. On average, only 33 percent of bird prey items identified to species were non-native species in 10 studies with 438 specimens of 58 species.” [1]

That’s quite a statement to make on the basis of just 10 studies (spanning 63 years*) and an average of fewer than eight specimens per species. And actually, one of the studies cited by Loss et al. was no study at all, but rather the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s two-page brochure Impacts of Feral and Free-ranging Domestic Cats on Wildlife in Florida (PDF). Not only are there no “bird prey items identified to species,” the document relies heavily on claims made by the American Bird Conservancy (thus raising serious doubts about the agency’s assertion that “scientific data drives management decisions for fish and wildlife populations and their habitats”).

How nobody—neither the three authors nor the multiple reviewers—caught this is a bit of a mystery. Just a glance at the brochure’s title ought to raise eyebrows in light of the way it’s cited by Loss et al. On the other hand, mistakes like this do happen. And in this case, I’m willing to give the authors the benefit of the doubt—largely because there are so many other, far more substantive, problems with their paper.

Which brings me back to those native bird species—seemingly targeted by free-roaming cats. It turns out that 57 of the 58 species (see table below) have been given a “Least Concern” conservation status by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The one exception, the Northern Bobwhite is considered “Near Threatened” because it has, according to BirdLife International, “undergone a large and statistically significant decrease over the last 40 years in North America.” The reason? “Widespread habitat fragmentation” and extensive hunting.**

So, let’s put all of this into perspective…

We are expected to believe:

1. “Free-ranging domestic cats kill 1.4–3.7 billion birds” each year, [1] an astonishing 28.5–75.5 percent of the estimated 4.7 billion landbirds in all of North America. [2] (That’s on top of the 21 percent Arnold and Zink attribute to collisions with towers and windows. [3])

and

2. Fifty-seven of the 58 native species identified by the authors as representing two-thirds of these mortalities remain abundant.

As I noted during my recent conversation with Animal Wise Radio hosts Mike Fry and Beth Nelson, it can’t all be true.

• • •

I recently asked Dennis Turner, editor and key contributor to The Domestic Cat: The Biology of its Behaviour (the third edition of which is due out sometime this year) and board member of the International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations, for his take on the Smithsonian’s “killer cat study.” “As I demonstrated at the Los Angeles Symposium of HSUS on The Outdoor Cat in December,” wrote Turner in reply, “such extrapolations of how many birds or rodents or reptiles/amphibians cats kill each year are absolutely meaningless on the species level if not put into context with the annual production of that species.” (his bold, his italics)

“Any claim that cats are a much ‘more significant anthropogenic threat’ than other factors (e.g., construction with loss of habitat, pollution, road traffic kills, etc.) are even more ridiculous, in that there are rarely estimates (good or poor) of deaths of birds/mammals/amphibians to such factors to compare with.”

* Five of the studies are more than 60 years old.

** BirdLife International claims that “over 20,000,000 individuals were recently being killed annually by hunters in the USA,” but I’ve yet to chase down the source cited.

Literature Cited

1. Loss, S.R., Will, T., and Marra, P.P., “The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States.” Nature Communications. 2013. 4. http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v4/n1/full/ncomms2380.html

2. T.D. Rich, C.J.B., H. Berlanga, P.J. Blancher, M.S. W. Bradstreet, G.S. Butcher, D.W. Demarest, and E.H. Dunn, W.C.H., E.E. Iñigo-Elias, J.A. Kennedy, A.M. Martell, A.O. Panjabi, D.N. Pashley, K.V. Rosenberg, C.M. Rustay, J.S. Wendt, T.C. Will., Partners in Flight North American Landbird Conservation Plan. 2004, Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY. www.partnersinflight.org/cont_plan/

3. Arnold, T.W. and Zink, R.M., “Collision Mortality Has No Discernible Effect on Population Trends of North American Birds.” PLoS ONE. 2011. 6(9): p. e24708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0024708