To hear The Wildlife Society’s staunch opponents of TNR tell it, the media’s just not interested in stories about “the impacts of free-ranging and feral cats on wildlife.”

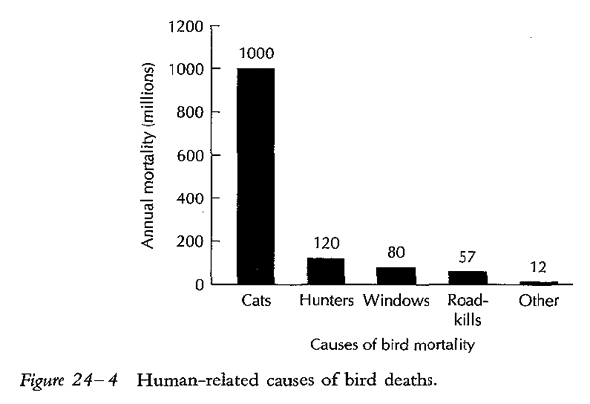

“This January when thousands of blackbirds fell from the sky in Arkansas, articles about mass extinctions and bird conservation were a dime-a-dozen. When the Deepwater Horizon oil spill killed 6,000 birds between April to October 2010, news organizations ran ‘Breaking News’ about the negative impacts on the environment. Meanwhile it is estimated that one million birds are killed everyday by cats, and the only news organizations covering it are small, local branches. The bigger problem is being shuffled to the backburner for more sensational news.”

According to The Wildlife Society (TWS), however, “the bigger problem” is “greater than almost any other single-issue.”

In their effort to get the issue on the front burner, TWS has “gathered the facts about these cats, and published them in the Spring Issue of The Wildlife Professional in a special section called ‘The Impact of Free Ranging Cats.’” (available free via issuu.com)

Thus armed, readers are expected to, as it says on the cover, “Pick One: Outdoor Cats or Conservation”

Back Burner or Hot Topic?

Before we get to the “facts,” it’s worth looking back over the past 15 months to see just how neglectful the media have been re: “the bigger problem.”

- January 9, 2010: Travis Longcore, science director for the Urban Wildlands Group, tells Southern California Public Radio: “Feral cats are documented predators of native wildlife. We do not support release of this non-native predator into our open spaces and neighborhoods, where they kill birds and other wildlife.”

- January 17, 2010 Longcore, whose Urban Wildlands Group was lead plaintiff in a lawsuit aimed to put an end to publicly supported TNR in Los Angeles, tells the L.A. Times: “It’s ugly; it’s gotten very vicious. It’s not like we’ve got a vendetta here. This is a real environmental issue, a real public health issue.” In the same story, American Bird Conservancy’s Senior Policy Advisor, Steve Holmer, tells the Times: “The latest estimates are that there are about . . . 160 million feral cats [nationwide]… It’s conservatively estimated that they kill about 500 million birds a year.”

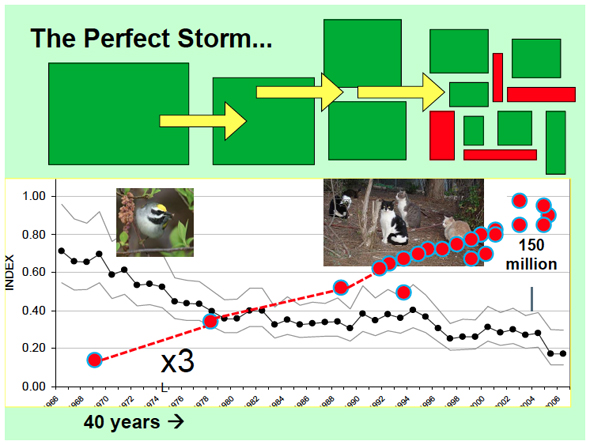

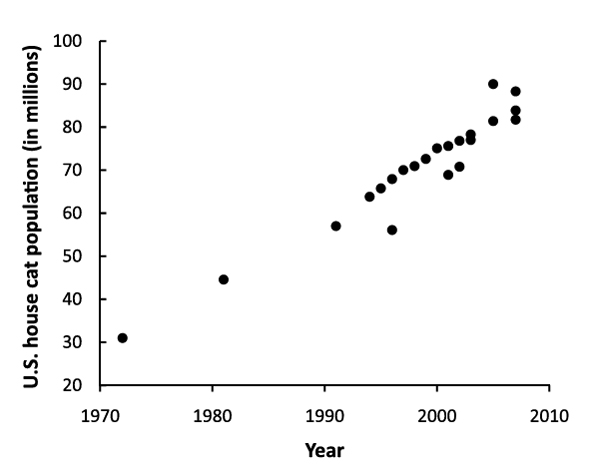

- September 30, 2010: “Scientists are quietly raging about the effects that cats, both owned and stray, are having on bird populations,” claims Washington Post columnist Adrian Higgins. “It’s not an issue that has received much attention, but with an estimated 90 million pet cats in the United States, two-thirds of them allowed outdoors, the cumulative effect on birds is significant, according to experts.” Higgins’ story is riddled with misinformation, courtesy of the American Bird Conservancy (ABC), The Wildlife Society, and Dauphine and Cooper’s 2009 Partners in Flight paper.

“Palmer said one of the most ‘heartbreaking’ scenes during filming was at a volunteer spay-neuter clinic in Los Angeles that sterilized 80 ferals a day. She said most of the cats had infections that never healed, as well as broken bones, large abscesses around their teeth and mange.” (A claim easily discredited, if only the reporters had bothered to check.)

- January 2011: Utah Representative Curtis Oda sponsors HB 210, which would permit “the humane shooting of an animal in an unincorporated area of a county, where hunting is not prohibited, if the person doing the shooting has a reasonable belief that the animal is a feral animal.”

Yet, the folks at TWS would have us believe that “the only news organizations covering [the cat-bird issue] are small, local branches.” As is often the case, their story doesn’t hold up well alongside the facts.

Indeed, other than when Higgins got Executive Director/CEO Michael Hutchins’ name wrong, it’s hard to see what TWS has to complain about.

The Art of Selling Science

“After years of arguments,” laments Nico Dauphine and Robert Cooper, recalling last year’s decision by Athens, GA, to adopt TNR, “the vote was cast: 9–1 in favor of the ordinance, with an additional 7–3 vote establishing a $10,000 annual budget to support the TNR program.”

“How could this happen in a progressive community like Athens, Georgia, home to one of the nation’s finest university programs in wildlife science? The answer is a complex mix of money, politics, intense emotions, and deeply divergent perspectives on animal welfare… If we’re going to win the battle to save wildlife from cats, then we’ll need to be smarter about how we communicate the science.” [1]

Something tells me this “smarter” communication doesn’t allow for much in the way of honesty and transparency—attributes already in short supply.

Old Habits

“The Impact of Free Ranging Cats” has given its contributors the opportunity to revive and reinforce a range of dubious claims, including the ever-popular exaggerations about the number of free-roaming cats in the environment.

According to Dauphine and Cooper, “The number of outdoor pet cats, strays, and feral cats in the U.S. alone now totals approximately 117 to 157 million,” [1] an estimate rooted in their earlier creative accounting. Colin Gillin, president of the American Association of Wildlife Veterinarians, who penned this issue’s “Leadership Letter” (more on that later), follows suit, claiming “60 million or more pet cats are allowed outdoors to roam free.” [2]

The American Pet Products Association 2008 National Pet Owners Survey, though, indicates that 64 percent of pet cats are indoor-only during the daytime, and 69 percent are kept in at night [3]. Of those that are allowed outdoors, approximately half are outside for less than three hours each day. [4, 5]

This information is widely available—and has been for years—yet many TNR opponents continue to inflate by a factor of two the number of free-roaming pet cats.

And it only gets worse from here.

Dense and Denser

Not content to inflate absolute cat numbers, Dauphine and Cooper go on to misrepresent research into population demographics as well. “Local densities can be extremely high,” they write, “reaching up to 1,580 cats per square kilometer in urban areas.” [1] In fact, the very paper they cite paints a rather different picture. For one thing, there’s quite a range involved: 132–1,579 cats per square kilometer (a point recognized by Yolanda van Heezik, another contributor to the special issue [6].)

Also, this is a highly skewed distribution—there are lots of instances of low/medium density, while high densities are far less common. As a result, the median (417) is used “as a measure of central tendency” [7] rather than the mean (856). So, although densities “reaching up to 1,580 cats per square kilometer in urban areas” were observed, more than half fell between 132 and 417 cats per square kilometer (or 51–161 cats per square mile).

Even more interesting, however, are what Sims et al. learned when they compared bird density and cat density: in many cases, there were more birds in the very areas where there were more cats—even species considered especially vulnerable to predation by cats. It may be, suggest Sims et al., that, because high cat density corresponds closely to high housing density, this measure is also an indication of those areas “where humans provide more supplementary food for birds.” [7]

Another explanation: “consistently high cat densities in our study areas… and thus uniformly high impacts of cat populations on urban avian assemblages.” [7] (Interestingly, the authors never consider that they might be observing uniformly low impacts.)

The bottom line? It’s difficult enough to show a direct link between observed predation and population impacts; suggesting a causal connection between high cat densities and declining bird populations is misleading and irresponsible. (Not that Dauphine and Cooper are the only ones to attempt it; recall that no predation data from Coleman and Temple’s “Wisconsin Study” were ever published, despite numerous news stories in which Temple referred to their existence in some detail [8–10].)

Predation Pressure

Dauphine and Cooper make a similar leap when, to buttress their claim that “TNR does not reduce predation pressure on native wildlife,” [1] they cite a study not about predation, but about the home ranges of 27 feral cats on Catalina Island.

While it’s true that the researchers found “no significant differences… in home-range areas or overlap between sterilized and intact cats,” [11] this has as much due to their tiny sample size as anything else. And the difference in range size between the four intact males and the four sterilized males was—while not statistically significant—revealing.

The range of intact males was 33–116 percent larger during the non-breeding season, and 68–80 percent larger during the breeding season. In his study of “house-bound” cats, Liberg, too, found differences: “breeding males had ranges of 350–380 hectares; ranges of subordinate, non-breeding males were around 80 hectares, or not much larger than those of females.” [12]

All of which suggests smaller ranges for males that are part of TNR programs. What any of this has to do with “predation pressure on native wildlife,” however, remains an open question.

On the other hand, Castillo and Clarke (whose paper Dauphine and Cooper cite) actually documented remarkably little predation among the TNR colonies they studied. In fact, over the course of approximately 300 hours of observation (this, in addition to “several months identifying, describing, and photographing each of the cats living in the colonies” [13] prior to beginning their research), Castillo and Clarke “saw cats kill a juvenile common yellowthroat and a blue jay. Cats also caught and ate green anoles, bark anoles, and brown anoles. In addition, we found the carcasses of a gray catbird and a juvenile opossum in the feeding area” [13].

Another of Dauphine and Cooper’s “facts”—that “TNR does not typically reduce feral cat populations”—is contradicted by another one of the studies they cite. Contrary to what the authors suggest, Felicia Nutter’s PhD thesis work showed that “colonies managed by trap-neuter-return were stable in composition and declining in size throughout the seven year follow-up period.” [14]

Indeed, Nutter observed a mean decrease of 36 percent (range: 30–89 percent) in the six TNR colonies they studied over two years. By contrast, the three control colonies increased in size an average of 47 percent. [15]

Additional TNR success stories Dauphine and Cooper fail to acknowledge:

- Natoli et al. reported a 16–32 percent decrease in population size over a 10-year period across 103 colonies in Rome—despite a 21 percent rate of “cat immigration.” [16]

- As of 2004, ORCAT, run by the Ocean Reef Community Association (in the Florida Keys), had reduced its “overall population from approximately 2,000 cats to 500 cats.” [17] According to the ORCAT Website, the population today is approximately 350, of which only about 250 are free-roaming.

Toxoplasma gondii

In recent years, Toxoplasma gondii has been linked to the illness and death of marine life, primarily sea otters [18], prompting investigation into the possible role of free-roaming (both owned and feral) cats. [19, 20] But if, as the authors claim, “the science points to cats,” then it does so rather obliquely, an acknowledgement Jessup and Miller make begrudgingly:

“Based on proximity and sheer numbers, outdoor pet and feral domestic cats may be the most important source of T. gondii oocysts in near-shore marine waters. Mountain lions and bobcats rarely dwell near the ocean or in areas of high human population density, where sea otter infections are more common.” [21, emphasis mine]

Correlation, however, is not the same as causation. And not all T. gondii is the same.

In a study of southern sea otters from coastal California, conducted between 1998 and 2004, a team of researches—including Jessup and Miller—found that 36 of 50 otters were infected with the Type X strain of T. gondii, one of at least four known strains. [22] Jessup and Miller were also among 14 co-authors of a 2008 paper (referenced in their contribution to “The Impact of Free Ranging Cats”) in which the Type X strain was linked not to domestic cats, but to wild felids:

“Three of the Type X-infected carnivores were wild felids (two mountain lions and a bobcat), but no domestic cats were Type X-positive. Examination of larger samples of wild and domestic felids will help clarify these initial findings. If Type X strains are detected more commonly from wild felids in subsequent studies, this could suggest that these animals are more important land-based sources of T. gondii for marine wildlife than are domestic cats.” [20, emphasis mine]

Combining the results of the two studies, then, nearly three-quarters of the sea otters examined as part of the 1998–2004 study were infected with a strain of T. gondii that hasn’t been traced to domestic cats. (I found this to be such surprising news that, months ago, I tried to contact Miller about it. Was I missing something? What studies were being conducted that might confirm or refute these finings? Etc. I never received a reply.)

As Miller et al. note, “subsequent studies” are in order. And it’s important to keep in mind their sample size was quite small: three bobcats, 26 mountain lions, and seven domestic cats (although the authors suggest at one point that only five domestic cats were included).

Still, a recently published study from Germany seems to support the hypothesis that the Type X strain isn’t found in domestic cats. Herrmann et al. analyzed 68 T. gondii-positive fecal samples (all from pet cats) and found no Type X strain. [23] (It’s interesting to note, too, that only 0.25 percent of the 18,259 samples tested positive for T. gondii.)

This is not to say that there’s no connection between domestic cats and Toxoplasmosis in sea otters, but that any “trickle-down effect,” as Jessup and Miller describe it, is not nearly as well understood as they imply. There’s too much we simply don’t know.

Money and Politics

I agree with Dauphine and Cooper that science is only part of the TNR debate—that it also involves “a complex mix of money, politics, intense emotions, and deeply divergent perspectives on animal welfare.” And I agree with their assessment of the progress being made by TNR supporters:

“Advocates of TNR have gained tremendous political strength in the U.S. in recent years. With millions of dollars in donor funding, they are influencing legislation and the policies of major animal-oriented nonprofit organizations.” [1]

What I find puzzling is Dauphine’s rather David-and-Goliath portrayal of the “cat lobby” (my term, not hers) they’re up against—in particular, her complaint, “promotion of TNR is big business, with such large amounts of money in play that conservation scientists opposing TNR can’t begin to compete.” [24]

The Cat Lobby

In “Follow the Money: The Economics of TNR Advocacy,” she notes that Best Friends Animal Society, “one of the largest organizations promoting TNR, took in over $40 million in revenue in 2009.” [24] Fair enough, but this needs to be weighed against expenses of $35.6 million—of which $15.5 million was spent on “animal care activities.”

But Dauphine’s got it wrong when she claims that Best Friends “spent more than $11 million on cat advocacy campaigns that year.” [24] Their financials—spelled out in the same document Dauphine cites—are unambiguous: $11.7 million in expenditures went to all “campaigns and other national outreach.” Indeed, there is no breakdown for “cat advocacy campaigns.”

Dauphine does a better job describing Alley Cat Allies’ 2010 financials: of the $5.2 million they took in, $3.3 million was spent in public outreach. But she’s overreaching in suggesting that their “Every Kitty, Every City” campaign is nationwide. For now, at least, it’s up and running in just “five major U.S. cities.”

Echoing Dauphine’s concerns, Florida attorney Pamela Jo Hatley decries ORCAT’s resources: “At a meeting hosted by the Ocean Reef Resort in June 2004,” recalls Hatley, “I learned that the ORCAT colony then had about 500 free-ranging cats, several paid employees, and an annual operating budget of some $100,000.” [25]

What Hatley fails to mention is how those resources have been used to make ORCAT a model for the rest of the country—using private donations. Hatley doesn’t seem to object to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service shelling out $50,000—of tax dollars—in 2007 to round up fewer than 20 cats (some of which were clearly not feral) along with 81 raccoons (53 of which were released alive) in the Florida Keys. [26, 27]

Following the Money

According to their 2008 Form 990, ORCAT took in about $278,000 in revenue, compared to $310,000 in expenses. How does that compare to some of the organizations opposing TNR? A quick visit to Guidestar.com helps put things in perspective.

- In 2009, ABC took in just under $6 million, slightly more than their expenses.

- TWS had $2.3 million in revenue in 2009, which was more than offset by expenses of $2.5 million.

- Friends of the National Zoo, which oversees the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, showed $15 million in revenue, just exceeding their 2009 expenses of $14.7 million. (The Smithsonian Institute topped $1 billion in both the revenue and expense categories.)

- And the National Audubon Society took in $61.6 million in 2008 (the most recent year for which information is available). And, despite expenses in excess of $86 million, finished the year with more than $255 million in net assets.

These numbers clearly don’t reflect the funding each organization dedicates to opposing TNR—but neither do they offer any evidence that, as Dauphine argues, “conservation scientists opposing TNR can’t begin to compete.”

Intense Emotions

Nobody familiar with the TNR debate would suggest that it’s not highly emotional. How can it be otherwise? Indeed, the very idea of decoupling our emotions from such important discourse is rather absurd.

Having an emotional investment in the debate does not, however, make one irrational or stupid.

“On the surface,” suggest Dauphine and Cooper, their tone unmistakably condescending, “TNR may sound reasonable, even logical.” [1] Gillin, for his part, bemoans the way the TNR debate “quickly shifts from statistics to politics to emotional arguments.” [2]

What’s particularly fascinating about all of this—the way TNR supporters are made out to be irrational (if not mentally ill—as in a letter to Conservation Biology last year, when several TNR opponents, including four contributors to “The Impact of Free Ranging Cats,” compared TNR to hoarding [28])—is just how emotionally charged the appeal of TNR opponents is.

Witness the “gruesome gallery of images,” for example, in which “one cat lies dead with a broken leg, one lies dying in a coat of maggots, and another suffers as ticks and ear mites plague its face.” [1] The idea, of course, is that these cats would have been better off if they’d been rounded up and killed “humanely.” A preemptive strike against the inevitability of “short, brutal lives.” (This phrase, which I first saw used by Jessup, [28] has become remarkably popular among TNR opponents.)

But is it that simple? Applying the same logic (if that’s what it is) to pelicans covered in oil, for instance, would we suggest that these birds should either be in captivity or “humanely euthanized”? Obviously not.

Divergent Perspectives on Animal Welfare

While I disagree that “the debate is predominately about whether cats should be allowed to run wild across the landscape and, if not, how to effectively and humanely manage them,” [29] I tend to agree with Lepczyk et al. when they write:

“It’s much more about human views and perceptions than science—a classic case where understanding the human dimensions of an issue is the key to mitigating the problem.” [29]

But, like Dauphine and Cooper, Lepczyk et al. seem more interested in broadcasting their message—loudly, ad nauseam—than in listening. “We need to understand whether people are even aware,” they write, “of the cumulative impact that their actions—choosing to let cats outdoors—can have on wildlife populations.” [29]

Although it’s packaged somewhat “softly,” we’re back to the same old speculative connections between predation and population impacts (familiar terrain for Lepczyk, who tried to connect these same dots in his PhD research). But how much of a connection is there, really? In their review of 61 predation studies, Mike Fitzgerald and Dennis Turner are unambiguous:

“We consider that we do not have enough information yet to attempt to estimate on average how many birds a cat kills each year. And there are few, if any studies apart from island ones that actually demonstrate that cats have reduced bird populations.” [30]

While the tone used by Lepczyk et al. is very much “we’re all in this together,” their prescription for “moving forward” suggests little common ground. (They actually cite that 2010 letter to Conservation Biology [28]—not much of an olive branch.)

“One approach is exemplified in Hawaii,” explain the authors, “where we’ve become part of a large coalition of stakeholders working together with the shared goal of reducing and eventually removing feral cats from the landscape.” [29] So, who’s involved?

“Our diverse group includes individuals from the Humane Society of the United States, the Hawaiian Humane Society, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, Hawaii’s Department of Land and Natural Resources, and the University of Hawaii. Our team also regularly interacts with other groups around the nation such as regional Audubon Societies and the American Bird Conservancy. Several stakeholders in the group have differing views, such as on whether or not euthanasia or culling is appropriate, or whether people should feed feral cats.” [29]

Other than the Humane Society organizations (whose position on TNR I don’t take for granted, considering they were early supporters of ABC’s Cats Indoors! campaign [31]), I don’t see a real diversity of views in this coalition.

I suppose it’s easy to make room at the table when you’re offering so few seats.

For Dauphine, though, any such collaboration approaches treason. Or selling out, at least.

“In some cases,” she explains, “conservation groups accept funding to join in efforts promoting TNR. The New Jersey Audubon Society, for example, had previously rejected TNR but began supporting it in 2005, acknowledging funding from the Frankenberg and Dodge Foundations for collaboration with TNR groups.” [24]

Dauphine doesn’t go into detail about the amount of funding, and it’s not clear what, if any, role it played in the decision by NJAS (which took in $6.8 million in 2008) to participate in the New Jersey Feral Cat-Wildlife Coalition—the kind of collaborative effort that should be encouraged, not derided:

“From 2002 to 2005, NJAS had actively opposed the practice of TNR in New Jersey. Despite this opposition, municipalities continued to adopt TNR ordinances. In 2005, NJAS, American Bird Conservancy, Neighborhood Cats and Burlington Feral Cat Initiative began exploratory dialogue about implementing standards to protect rare wildlife vulnerable to cat predation in towns which have already adopted TNR programs.” [32]

Message Received, Loud and Clear

Rather than wringing their hands over how to “better communicate the science” [1] or how to better facilitate “legal or policy changes, incentives, and increased education,” [29] TNR opponents might want to reconsider the message itself.

What they are proposing is the killing—on an unprecedented scale—of this country’s most popular pet.

I don’t imagine this tests well with focus groups and donors, of course, but there it is.

These people seem perplexed by a community’s willingness to adopt TNR (“In the end,” lament Lepczyk et al., referring to the decision in Athens, GA, “the professional opinion of wildlife biologists counted no more than that of any other citizen, a major reason for the defeat.” [29]) but fail to recognize how profoundly unpalatable their alternative is.

And, unworkable, too.

Which may explain why it’s virtually impossible to get them to discuss their “plan” in any detail. (I was unsuccessful, for example, in pinning down Travis Longcore during our back-and-forth on the Audubon magazine’s blog and couldn’t get Jessup or Hutchins to bite when I asked the same question during an online discussion of public health risks.)

In light of what’s involved with “successful” eradication programs, I’m not surprised by their eagerness to change the subject.

- On Marion Island, it took 19 years to eradicate something like 2,200 cats—using disease (feline distemper), poisoning, intensive hunting and trapping, and dogs. This on an island that’s only 115 square miles in total area, barren, and uninhabited. [33, 34] The cost, I’m sure, was astronomical.

- On the sparsely populated (fewer than 1,000, according to Wikipedia) Ascension Island (less than 34 total square miles), a 2003 eradication effort cost nearly $950,000 (adjusted to 2009 dollars). [35]

- A 2000 effort on Tuhua (essentially uninhabited, and just 4.9 square miles) ran $78,591 (again, adjusted to 2009 dollars). [35]

- Efforts on Macquarie Island (also small—47.3 square miles—and essentially uninhabited) proved particularly costly: $2.7 million in U.S. (2009) dollars. And still counting. The resulting rebound in rabbit and rodent numbers prompted “Federal and State governments in Australia [to commit] AU$24 million for an integrated rabbit, rat and mouse eradication programme.” [36] (To put this into context, Macquarie Island is about one-third the size of the Florida Keys.)

These examples represent, in many ways, low-hanging fruit. By contrast, “the presence of non-target species and the need to safely mitigate for possible harmful effects, along with substantial environmental compliance requirements raised the cost of the eradication.” [37] Eradicating rodents from Anacapa Island, “a small [1.2-square-mile] island just 80 miles from Los Angeles International Airport, cost about $2 million.” [38]

Now—setting aside the horrors involved—how exactly do TNR opponents propose to rid the U.S. of it’s millions of feral cats? [cue the sound track of crickets chirping]

I think the general public is starting to catch on. Even if they fall for the outlandish claims about predation, wildlife impacts, and all the rest—they don’t see anything in the way of a real solution. As Mark Kumpf, former president of the National Animal Control Association, put it in an interview with Animal Sheltering magazine, “the traditional methods that many communities use… are not necessarily the ones that communities are looking for today.” [39]

“Traditional” approaches to feral cat management (i.e., trap-and-kill) are, says Kumpf, akin to “bailing the ocean with a thimble.” [39]

For all their apparent interest—22 pages in the current issue of The Wildlife Professional alone—TWS might as well be handing out thimbles to its members. Although Gillin’s “Leadership Letter” invites “dialogue among all stakeholders,” it offers nothing substantive to advance the discussion:

“If removal and euthanasia of unadoptable feral cats is not acceptable to TNR proponents, then they need to offer the conservation community a logical, science-based proposal that will solve the problem of this invasive species and its effect on wildlife and the environment.” [2]

So much for leadership.

Literature Cited

1. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., “Pick One: Outdoor Cats or Conservation.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 50–56.

2. Gillin, C., “The Cat Conundrum.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 10, 12.

3. APPA, 2009–2010 APPA National Pet Owners Survey. 2009, American Pet Products Association: Greenwich, CT. http://www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp

4. Lord, L.K., “Attitudes toward and perceptions of free-roaming cats among individuals living in Ohio.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2008. 232(8): p. 1159-1167. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_232_8_1159.pdf

5. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.1541

6. van Heezik, Y., “A New Zealand Perspective.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 70.

7. Sims, V., et al., “Avian assemblage structure and domestic cat densities in urban environments.” Diversity and Distributions. 2008. 14(2): p. 387–399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00444.x

8. Wilson, M. (1997). Cats Roaming Free Take a Toll on Songbirds. Boston Globe, p. 11.

9. Seppa, N. (1993, July 22). Millions of Songbirds, Rabbits Disappearing. Wisconsin State Journal, p. 1A.

10. Wozniak, M.D. (1993, August 3). Feline felons: Barn cats are just murder on songbirds. The Milwaukee Journal, p. A1.

11. Guttilla, D.A. and Stapp, P., “Effects of sterilization on movements of feral cats at a wildland-urban interface.”Journal of Mammalogy. 2010. 91(2): p. 482–489. http://dx.doi.org/10.1644/09-MAMM-A-111.1

12. Liberg, O. and Sandell, M., Spatial organisation and reproductive tactics in the domestic cat and other felids, in The Domestic cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York. p. 83–98.

13. Castillo, D. and Clarke, A.L., “Trap/Neuter/Release Methods Ineffective in Controlling Domestic Cat “Colonies” on Public Lands.” Natural Areas Journal. 2003. 23: p. 247–253.

14. Nutter, F.B., Evaluation of a Trap-Neuter-Return Management Program for Feral Cat Colonies: Population Dynamics, Home Ranges, and Potentially Zoonotic Diseases, in Comparative Biomedical Department. 2005, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC. p. 224.

15. Stoskopf, M.K. and Nutter, F.B., “Analyzing approaches to feral cat management—one size does not fit all.”Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1361–1364. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552309

www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1361.pdf

16. Natoli, E., et al., “Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy).” Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2006. 77(3-4): p. 180-185. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TBK-4M33VSW-1/2/0abfc80f245ab50e602f93060f88e6f9

www.kiccc.org.au/pics/FeralCatsRome2006.pdf

17. Levy, J.K. and Crawford, P.C., “Humane strategies for controlling feral cat populations.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1354–1360. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/default.asp

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1354.pdf

18. Jones, J.L. and Dubey, J.P., “Waterborne toxoplasmosis – Recent developments.” Experimental Parasitology. 124(1): p. 10-25. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6WFH-4VXB8YT-2/2/8f9562f64497fe1a30513ba3f000c8dc

19. Dabritz, H.A., et al., “Outdoor fecal deposition by free-roaming cats and attitudes of cat owners and nonowners toward stray pets, wildlife, and water pollution.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2006. 229(1): p. 74-81. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_229_1_74.pdf

20. Miller, M.A., et al., “Type X Toxoplasma gondii in a wild mussel and terrestrial carnivores from coastal California: New linkages between terrestrial mammals, runoff and toxoplasmosis of sea otters.” International Journal for Parasitology. 2008. 38(11): p. 1319-1328. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4RXJYTT-2/2/32d387fa3048882d7bd91083e7566117

21. Jessup, D.A. and Miller, M.A., “The Trickle-Down Effect.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 62–64.

22. Conrad, P.A., et al., “Transmission of Toxoplasma: Clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels of Toxoplasma gondii flow into the marine environment.” International Journal for Parasitology. 2005. 35(11-12): p. 1155-1168. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4GWC8KV-2/2/2845abdbb0fd82c37b952f18ce9d0a5f

23. Herrmann, D.C., et al., “Atypical Toxoplasma gondii genotypes identified in oocysts shed by cats in Germany.”International Journal for Parasitology. 2010. 40(3): p. 285–292. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4X1J771-2/2/dc32f5bba34a6cce28041d144acf1e7c

24. Dauphine, N., “Follow the Money: The Economics of TNR Advocacy.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 54.

25. Hatley, P.J., “Incompatible Neighbors in the Florida Keys.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 52–53.

26. O’Hara, T. (2007, April 3). Fish & Wildlife Service to begin removing cats from Keys refuges. The Key West Citizen, from http://keysnews.com/archives

27. n.a., Lower Florida Keys National Wildlife Refuges Comprehensive Conservation Plan. 2009, U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service: Atlanta, GA. http://www.fws.gov/nationalkeydeer/

http://www.fws.gov/southeast/planning/PDFdocuments/Florida%20Keys%20FINAL/TheKeysFinalCCPFormatted.pdf

28. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552312

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1377.pdf

29. Lepczyk, C.A., van Heezik, Y., and Cooper, R.J., “An Issue with All-Too-Human Dimensions.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 68–70.

30. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

31. Berkeley, E.P., TNR Past present and future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement. 2004, Bethesda, MD: Alley Cat Allies.

32. Stiles, E., NJAS Works with Coalition to Reduce Bird Mortality from Outdoor Cats. 2008, New Jersey Audubon Society. http://www.njaudubon.org/Portals/10/Conservation/PDF/ConsReportSpring08.pdf

33. Bester, M.N., et al., “A review of the successful eradication of feral cats from sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Southern Indian Ocean.” South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 2002. 32(1): p. 65–73.

http://www.ceru.up.ac.za/downloads/A_review_successful_eradication_feralcats.pdf

34. Bloomer, J.P. and Bester, M.N., “Control of feral cats on sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Indian Ocean.” Biological Conservation. 1992. 60(3): p. 211-219. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V5X-48XKBM6-T0/2/06492dd3a022e4a4f9e437a943dd1d8b

35. Martins, T.L.F., et al., “Costing eradications of alien mammals from islands.” Animal Conservation. 2006. 9(4): p. 439–444. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00058.x/abstract

http://i3n.iabin.net/documents/pdf/Costingeradicationsofalienmammalsfromislands.pdf

36. Bergstrom, D.M., et al., “Indirect effects of invasive species removal devastate World Heritage Island.” Journal of Applied Ecology. 2009. 46(1): p. 73-81. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01601.x/abstract

http://eprints.utas.edu.au/8384/4/JAppEcol_Bergstrom_etal_journal.pdf

37. Donlan, C.J. and Heneman, B., Maximizing Return on Investments for Island Restoration with a Focus on Seabird Conservation. 2007, Advanced Conservation Strategies: Santa Cruz, CA. http://www.advancedconservation.org/roi/ACS_Seabird_ROI_Report.pdf

38. Donlan, C.J. and Wilcox, C., Complexities of costing eradications, in Animal Conservation. 2007, Wiley-Blackwell. p. 154–156. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2007.00101.x/abstract

http://www.advancedconservation.org/library/donlan_&_wilcox_2007a.pdf

39. Hettinger, J., Taking a Broader View of Cats in the Community, in Animal Sheltering. 2008. p. 8–9. http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/taking_a_broader_view_of_cats.html

http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/broader_view_of_cats.pdf

Evidence of cats as pets? In

Evidence of cats as pets? In  Wind turbine near Walnut, Iowa. Photo courtesy of

Wind turbine near Walnut, Iowa. Photo courtesy of