Although Nico Dauphine has yet to be suspended from her duties at the Smithsonian’s Migratory Bird Center, it seems all the attention she’s received over the past week-and-a-half is making life rather uncomfortable for her supporters.

Last week, the National Zoo removed Dauphine’s online application for recruiting field assistants from its Website; this week, the University of Georgia’s Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources pulled her infamous “Apocalypse Meow” presentation from its site.

Which is understandable, given the circumstances. Far more puzzling is what it was doing there in the first place. The content is, not surprisingly, remarkably “selective” in terms of the science. What is surprising, though, is Dauphine’s delivery: she looks and sounds like a person without the least bit of conviction in the material she’s presenting. (Actually, she’s mostly reading to the audience—for 41 minutes.)

Dauphine (whose status hearing, originally scheduled for June 1, has been postponed until the 15th) presented “Apocalypse Meow: Free-ranging Cats and the Destruction of American Wildlife” in March of 2009, at Warnell (where she earned her PhD). Although she tells the audience that her goal “is to review and present the best available science that we have,” what she delivers is essentially no different from what she presented in her Partners In Flight conference paper [1] (much of which is recycled in the current issue of The Wildlife Professional in a special section called “The Impact of Free Ranging Cats” [2]).

In other words: lots of exaggerated and misleading claims—and plenty of glaring omissions (i.e., the distinction between compensatory and additive predation).

Included in the section on predation are all the usual suspects: Longcore et al., [3] Coleman and Temple, [4] Crooks and Soulé, [5] PhD dissertations by both Christopher Lepczyk [6] and Cole Hawkins, [7] along with references to Linda Winter, David Jessup, [8] Pamela Jo Hatley, and others.

Among the highlights:

Invasive Species (of All Kinds)

Referring to island extinctions, Dauphine references a 2008 paper by Dov Sax and Steven Gaines—the same one the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service cite (again, as “evidence” of island extinctions caused by cats) in their Florida Keys National Wildlife Refuges Complex Integrated Predator Management Plan/Draft Environmental Assessment, released earlier this year. As I point out in my response to the Keys plan, though, the Sax & Gaines paper isn’t about cats at all, but invasive plants. [9]

Magic Multipliers

For Dauphine, Lepczyk’s estimated 52 birds/cat/year predation rate simply isn’t enough. Studies using “prey returns,” she argues, underestimate the real damage. “Some studies using radio-collars and other techniques have shown that, typically, cats will return maybe one in three kills that they make, and sometimes not at all—so this is, again, a very conservative estimate of the actual number of kills.”

But Lepczyk’s PhD work wasn’t based on “prey returns” at all. He used a survey (one of many flaws), asking landowners, “how many dead or injured birds a week do all the cats bring in during the spring and summer months?” [6]

And the idea that cats return only one in every three kills? That’s based on some wonky analysis by Kays and DeWan, who studied the hunting behaviors of just 24 cats: 12 that returned prey home, and another 12 (11 pets and 1 feral) that were observed hunting for a total of 181 hours (anywhere from 4.8–46.5 hours per cat). [10]

The Selective Generalist

Dauphine stretches Hawkins’ conclusions (which Hawkins himself had already stretched past the point of being defensible) to suggest “a sort of preferential prey take for native species in some cases, by cats.” In other words, the cats might target native species.

Or not. Less than two minutes later, Dauphine’s making the case for hyperpredation—the devastating impact on native prey species (e.g., seabirds) brought about by a large population of cats supported largely by predation on an introduced prey species (e.g., rabbits).

From Millions to Billions

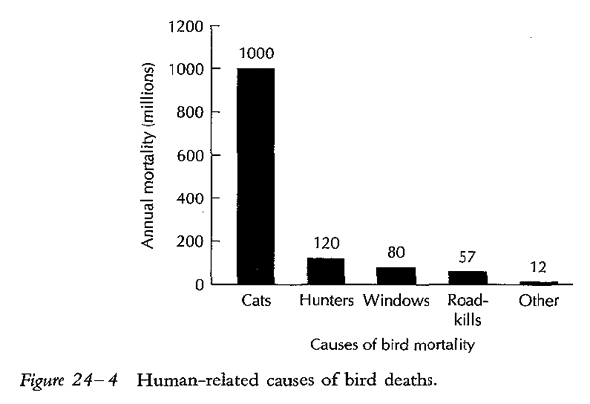

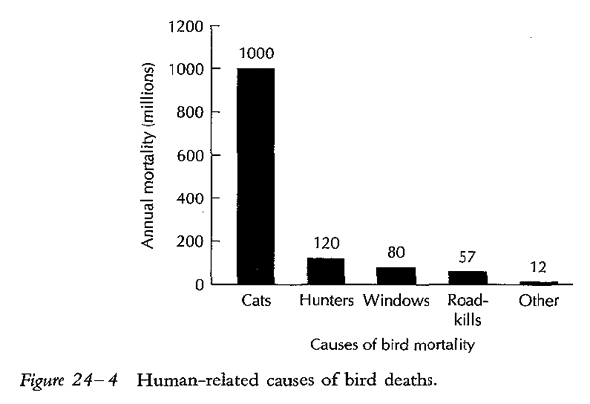

It’s difficult not to see Dauphine’s assertion that “it’s not productive to argue about the numbers”—which comes fairly early in her presentation—as disingenuous when she tries repeatedly to quantify predation levels (each of which is then qualified as “conservative”). Her use of a graph included in the second edition of Frank Gill’s Ornithology (shown below) is particularly interesting.

Now, the original source of Gill’s cat “data,” as Dauphine acknowledges, is Rich Stallcup’s 1991 article, “A reversible catastrophe”—inexplicably, the only source Gill cites when he refers to predation by cats: “Domesticated cats in North America may kill 4 million songbirds every day, or perhaps over a billion birds each year (Stallcup 1991). Millions of hungrier, feral (wild) cats add to this toll…” [11]

And where does Stallcup’s “data” come from?

“He simply argued—he didn’t do a study—he just argued that if one in ten of those cats kills one bird per day, already then we have 1.6 billion cat-killed birds per year,” explains Dauphine. “We actually know that the numbers are much larger. For instance, he’s starting out with 55 million pet cats; we know there are over 100 million outdoor cats in this country, and possibly far more. We also know from some studies that 80 percent of cats hunt, and the number of birds killed per year are probably much higher. So again, just to emphasize: this is a conservative estimate.”

In fact, Stallcup’s “estimate” is even flimsier than Dauphine suggests:

“Let’s do a quick calculation, starting with numbers of pet cats. Population estimates of domestic house cats in the contiguous United States vary somewhat, but most agree the figure is between 50 and 60 million. On 3 March 1990, the San Francisco Chronicle gave the number as 57.9 million, ‘up 19 percent since 1984.’ For this assessment, let’s use 55 million.

Some of these (maybe 10 percent) never go outside, and maybe another 10 percent are too old or too slow to catch anything. That leaves 44 million domestic cats hunting in gardens, marshes, fields, thickets, empty lots, and forests.

It is impossible to know how many of those actively hunting animals catch how many birds, but the numbers are high. To be very conservative, say that only one in ten of those cats kills only one bird a day. This would yield a daily toll of 4.4 million songbirds!! Shocking, but true—and probably a low estimate (e.g., many cats get multiple birds a day).” [12]

Shocking, yes. True? Why would anybody think so? (I can see the appeal for Dauphine, though: like her, Stallcup grossly overestimates the number of pet cats allowed outdoors.)

(The fact that this absurdity made it—however well disguised—into a standard ornithology textbook may explain a great deal about the positions frequently taken by today’s wildlife managers and conservation biologists regarding feral cats/TNR.)

Apocalypse Now

Perhaps the strangest—almost surreal—part of “Apocalypse Meow” comes when, to illustrate her point that the (over)heated TNR debate can “result in a lot of misunderstandings, misinformation, and hard feelings,” Dauphine refers to an e-mail sent out to the university’s CATSONCAMPUS listserv during the fierce TNR debate in Athens, which read in part:

“There are some folks in the area (and all over) who are not only Anti-TNR, they also hate felines so much that some of them want to round up the cats in the area and kill them.”

Two years later, this is pretty much what Nico Dauphine stands accused of.

Literature Cited

1. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2009. p. 205–219. http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/pif/pubs/McAllenProc/articles/PIF09_Anthropogenic%20Impacts/Dauphine_1_PIF09.pdf

2. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., “Pick One: Outdoor Cats or Conservation.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 50–56.

3. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap-Neuter-Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894. http://www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/pdf/Management_claims_feral_cats.pdf

4. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., “Rural Residents’ Free-Ranging Domestic Cats: A Survey.” Wildlife Society Bulletin. 1993. 21(4): p. 381–390. http://www.jstor.org/pss/3783408

5. Crooks, K.R. and Soulé, M.E., “Mesopredator release and avifaunal extinctions in a fragmented system.” Nature. 1999. 400(6744): p. 563–566. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v400/n6744/abs/400563a0.html

6. Lepczyk, C.A., Mertig, A.G., and Liu, J., “Landowners and cat predation across rural-to-urban landscapes.” Biological Conservation. 2003. 115(2): p. 191–201. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V5X-48D39DN-5/2/d27bfff8454a44161f8dc1ad7cc585ea

7. Hawkins, C.C., Impact of a subsidized exotic predator on native biota: Effect of house cats (Felis catus) on California birds and rodents. 1998, Texas A&M University

8. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552312

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1377.pdf

9. Sax, D.F. and Gaines, S.D., Species invasions and extinction: The future of native biodiversity on islands, in In the Light of Evolution II: Biodiversity and Extinction,. 2008: Irvine, CA. p. 11490–11497. www.pnas.org/content/105/suppl.1/11490.full

http://www.pnas.org/content/105/suppl.1/11490.full.pdf

10. Kays, R.W. and DeWan, A.A., “Ecological impact of inside/outside house cats around a suburban nature preserve.” Animal Conservation. 2004. 7(3): p. 273-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1367943004001489

www.nysm.nysed.gov/staffpubs/docs/15128.pdf

11. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 2nd ed. 1995, New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

12. Stallcup, R., “A reversible catastrophe.” Observer 91. 1991(Spring/Summer): p. 8–9. http://www.prbo.org/cms/print.php?mid=530

http://www.prbo.org/cms/docs/observer/focus/focus29cats1991.pdf