A Gray Catbird in Madison, Wisconsin, USA. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons and John Benson.

A Gray Catbird in Madison, Wisconsin, USA. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons and John Benson.

Once again, the Smithsonian has apparently put marketing (and perhaps politics, too) ahead of science, reviving a story first posted on the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center’s (SMBC) Website in October of last year (which has since been removed).

“Alarming number of fledgling, suburban catbirds fall prey to domestic cats, study finds,” reads the headline of the most recent version—posted not on the SMBC site, but as a feature story on Science at the Smithsonian, “a new Website from the Smithsonian Office of Public Affairs.” So what’s changed in the four months since I first commented on the story? Only the publication of the research involved: “Population demography of Gray Catbirds in the suburban matrix: Sources, sinks and domestic cats” by Anne L. Balogh, Thomas B. Ryder, and Peter P. Marra (all of whom are affiliated with the Migratory Bird Center) appeared in the January issue of the Journal of Ornithology.

Whoever wrote the piece for the Smithsonian, though, doesn’t seem to have read the paper.

Indeed, it seems the people responsible for its publication are far more interested in making scapegoats out of the cats than they are in science, or science journalism.

Predation: Real and Imagined

According to the Smithsonian, “Nearly half (47 percent) of the [juvenile catbird] deaths were attributed to domestic cats in Opal Daniels and Spring Park.”

In “Population demography of Gray Catbirds,” the authors report that the Opal Daniels and Spring Park sites accounted for 34 of 42 total juvenile mortalities. [1] The presumption, then, is that 16 (47 percent) are due to cats. However, cats accounted for—at most—just nine of the 42 total mortalities (no breakdown regarding cat kills/site is provided in the paper).

Something doesn’t add up here—and I suspect it’s no accident.

But attributing even nine kills to cats is highly questionable; only six were actually observed. The researchers then attributed three additional kills to cats, claiming: “we are unaware of any other native or non-native predator that regularly decapitates birds while leaving the body uneaten.” [1]

As I’ve pointed out previously, though, a survey of several credible sources [2–5] turns up no supporting evidence. Anderson, describing “predation and its identification,” goes into some detail:

“Domestic cats rarely prey on anything larger than a duck, pheasant, or rabbit. Einarsen (1956) noted their messy feeding behavior. Portions of their prey are often strewn over several hundred square feet in open areas. The meaty portions of large birds are almost entirely consumed leaving loose skin with feathers attached. Small birds are generally consumed, with only the wings, and scattered feathers remaining. Cats usually leave teeth marks on every exposed bone of their prey.” [6]

Raccoons, writes Anderson, are also known to “prey on birds and their eggs. The heads of adult birds are usually bitten off and left some distance from the body (Anon. 1936).” [6]

And it seems to be common knowledge within the birding community that certain species of birds decapitate their prey:

“In urban and suburban settings grackles are the most likely culprits, although jays, magpies, and crows will decapitate small birds, too. Screech-owls and pygmy-owls also decapitate their prey, but, intending to eat them later, they usually cache their victims out of sight.” [7]

“There is little you can do to discourage screech-owls if only because they do their killing under cover of darkness. However, you can recognize their handiwork by looking for partially plucked carcasses of songbirds with the heads missing… Corvids—crows, ravens, jays, and magpies—are well known for their raids on birds’ nests to take eggs and nestlings.” [8] (Interestingly, the author, David M. Bird, was among Marra’s nine co-authors on “What Conservation Biologists Can Do.”)

Balogh, Ryder, and Marra also point out that another “potential nest predator,” the gray squirrel, was more common at the Opal Daniels and Spring Park sites than at the Bethesda site. [1] And roughly three to five times as abundant as cats, based on researcher sightings. Yet the squirrels aren’t mentioned at all in the Smithsonian story.

Populations and Ecological Traps

In addition, Marra’s suggestion that “these suburban areas [are] ecological traps for nesting birds” is contradicted by the results of bird surveys in Maryland.

The Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia, for example reports: “during the Atlas period [1983–87], gray catbirds were found throughout the state, including the most heavily urbanized blocks.” The Atlas goes on to note the bird’s “high tolerance for human activity,” concluding that “the gray catbird’s future in Maryland seems secure.” [9]

Data from the Atlas indicate that Maryland’s gray catbird population declined perhaps 7 percent between 1966–1989, a period during which the state’s human population grew approximately 35 percent. (Note: In my previous post on this topic, I mistakenly suggested that the Atlas used Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data, which is not the case.)

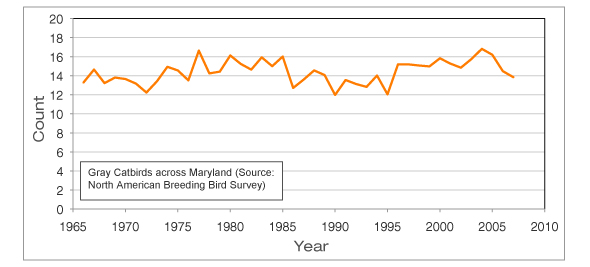

The North American Breeding Bird Survey indicates that Maryland’s gray catbird population has increased about 9 percent between 1966–2009, a period during which the state’s human population grew approximately 57 percent. And data from BBS Route 46110, the nearest to the research sites, also trend upward in recent years. (Note: It’s important to point out that “the survey produces an index of relative abundance rather than a complete count of breeding bird populations.”)

Caption: BBS Data: Gray Catbird Counts Across Maryland, 1966–2007

Caption: BBS Data: Gray Catbird Counts Across Maryland, 1966–2007

The Migratory Bird Center’s Website, too, suggests the outlook for the catbird population is quite good:

“To thrive in these [fragmented] habitats birds must have special adaptations such as the ability to respond to frequent nest predation and parasitism and to forage on a wide variety of seasonally available foods. Armed with these adaptations, catbirds are well prepared for the disturbed habitats of the 21st century’s fragmented landscape.”

• • •

Marra revealed his position on free-roaming cats last year in that letter to Conservation Biology opposing TNR. Among the “highlights” were the authors’ assertion that “trap-neuter-return is essentially cat hoarding without walls,” and a demand for “legal action against colonies and colony managers.” The authors also call on conservation biologists to “begin speaking out” against TNR “at local meetings, through the news media, and at outreach events” (a message Marra has obviously taken to heart).

In the past couple of months, the Smithsonian has raised questions about its own stance on free-roaming cats, first with its World’s Most Invasive Mammals story, and now this. In both cases, their reporting has been either careless or intentionally misleading.

According to its Website, the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center is a “national and international leader in the biology and conservation of migratory birds.” In this case, though, it seems the SMBC—and, by extension, Science at the Smithsonian—have abdicated any leadership role in order to participate in the shameful witch hunt against free-roaming cats.

The Institution’s supporters—and the public at large—expect and deserve better.

Literature Cited

1. Balogh, A., Ryder, T., and Marra, P., “Population demography of Gray Catbirds in the suburban matrix: sources, sinks and domestic cats.” Journal of Ornithology. 2011: p. 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0648-7

http://nationalzoo.si.edu/scbi/migratorybirds/science_article/pdfs/55.pdf

2. Tabor, R., Cats—The Rise of the Cat. 1991, London: BBC Books.

3. Leyhausen, P., Cat behavior: The predatory and social behavior of domestic and wild cats. Garland series in ethology. 1979, New York: Garland STPM Press. xv, 340 p.

4. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

5. Turner, D.C. and Meister, O., Hunting Behaviour of the Domestic Cat, in The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. p. 222.

6. Anderson, T.E., Identifying, evaluating and controlling wildlife damage, in Wildlife Management Techniques. 1969, Wildlife Society: Washington. p. 497–520.

7. Thompson, B., The Backyard Bird Watcher’s Answer Guide. 2008: Bird Watcher’s Digest.

8. Bird, D.M., Crouching Raptor, Hidden Danger, in The Backyard Birds Newsletter. 2010, Bird Watcher’s Digest.

9. Robbins, C.S. and Blom, E.A.T., Atlas of the breeding birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. Pitt series in nature and natural history. 1996, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. xx, 479 p.