For more than 20 years now, Gill’s classic text has been required reading for ornithology students. While the book’s attention to conservation issues has expanded over its three editions, its treatment of the impact of cats on bird populations reflects an unsettling shift away from science.

The hoards of students descending upon college campuses this fall will—despite the rise of the eco-friendly PDF and a great variety of online content—more often than not find their arms and backpacks stuffed with old-school printed-and-bound books. Among them will be Frank Gill’s Ornithology, a regular offering on campus bookstore shelves for 21 years now.

Gill’s Ornithology is, I’m told by one Vox Felina reader, “considered (at least in these parts) the text regarding ornithology.” From what I can tell, it’s popularity as required reading for third- and fourth-year undergraduates isn’t limited to any one region of the country. Indeed, according to Amazon.com, the book is “the classic text for the undergraduate ornithology course.” Its third edition, published in 2007, “maintains the scope and expertise that made the book so popular while incorporating a tremendous amount of new research.”

Unfortunately, none of this new research made it into the section—a single paragraph—meant to address the “threat” of cats. Indeed, students interested in this topic are better off with the first edition, published 17 years earlier.

First Edition

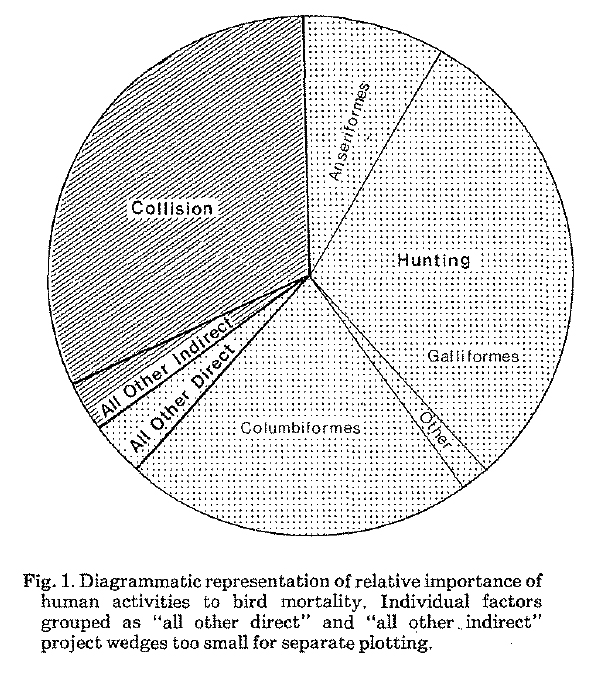

“The numbers of deaths attributable directly or indirectly to human actions each year during the 1970s are staggering,” writes Gill in the 1990 edition of Ornithology, “but are apparently minor in relation to the population level.” [1] Citing a 1979 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report by Richard C. Banks, Gill continues:

“Human activities are responsible for roughly 270 million bird deaths every year in the continental United States. This seemingly huge number is less than two percent of the 10 to 20 billion birds that inhabit the continental United States and appears to have no serious effect on the viability of any of the populations themselves, unlike human destruction of breeding habitat and interference with reproduction… Miscellaneous accidents such as impact with golf balls, electrocution by transmission lines, and cat predation, may amount to 3.5 million deaths a year.” [1]

Predation by cats (included under “All Other Indirect”), then, according to Banks, represents about 1.3 percent of overall human-caused mortality—a loss of, at most, 0.04 percent of the U.S. bird population annually. By contrast, hunting and “collision with man-made objects” combine to make up “about 90 percent of the avian mortality documented” in Banks’ report. [2]

Second Edition

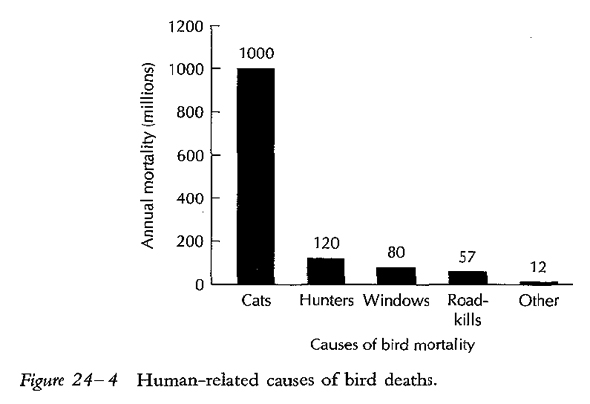

Five years later, in the second edition, the story changes dramatically. Gill discards Banks’ reference to cats and uses his 270 million figure purely for dramatic effect—the set-up for a punch line in the form of Rich Stallcup’s back-of-the-envelope guesswork (which Stallcup himself considered “probably a low estimate” [3]). Gill even includes a bar chart to drive the point home. (Apparently, he didn’t find Banks’ pie chart compelling enough to include in the his first edition of Ornithology.)

“Human activities are directly responsible for roughly 270 million bird deaths every year in the continental United States, about 2 percent of the 10 to 20 billion birds that inhabit the continental United States (Banks 1979)… Dwarfing these losses are those attributable to predation by pets. Domesticated cats in North America may kill 4 million songbirds every day, or perhaps over a billion birds each year (Stallcup 1991). Millions of hungrier, feral (wild) cats add to this toll, which is not included in the estimate of 270 million bird deaths each year.” [4]

But Stallcup’s “estimate”—published in the Observer, a publication of the Point Reyes Bird Observatory (which Stallcup co-founded)—lacks even the slightest scientific justification. In fact, “A Reversible Catastrophe” is little more than Stallcup’s advice—at once both folksy and sinister—about defending one’s garden from neighborhood cats (“…try a B-B or pellet gun. There is no need to kill or shoot toward the head, but a good sting on the rump seems memorable for most felines, and they seldom return for a third experience.” [3]).

“Let’s do a quick calculation, starting with numbers of pet cats. Population estimates of domestic house cats in the contiguous United States vary somewhat, but most agree the figure is between 50 and 60 million. On 3 March 1990, the San Francisco Chronicle gave the number as 57.9 million, ‘up 19 percent since 1984.’ For this assessment, let’s use 55 million.

“Some of these (maybe 10 percent) never go outside, and maybe another 10 percent are too old or too slow to catch anything. That leaves 44 million domestic cats hunting in gardens, marshes, fields, thickets, empty lots, and forests.

“It is impossible to know how many of those actively hunting animals catch how many birds, but the numbers are high. To be very conservative, say that only one in ten of those cats kills only one bird a day. This would yield a daily toll of 4.4 million songbirds!! Shocking, but true—and probably a low estimate (e.g., many cats get multiple birds a day).” [3]

It’s hardly surprising that Stallcup’s “estimate” grossly exaggerates predation rates since his research never went any further than the Chronicle’s mention of the U.S. pet cat population. His assumptions about how many of these cats go outdoors and their success as hunters stand in stark contrast to the trend suggested by pet owner survey results and various predation studies (some of which suggest that just 36–56 percent of cats are hunters. [5, 6])

(It was, no doubt, the “shocking” aspect of Stallcup’s numbers that appealed to Nico Dauphine, who, in her “Apocalypse Meow” presentation, acknowledges that Stallcup “didn’t do a study” but nevertheless concludes, inexplicably, that his “is a conservative estimate.”)

Unnatural Selection

So, how did Stallcup’s indefensible “estimate” make it into the standard ornithology textbook? It was, Gill told me recently by e-mail, “one of the few refs [he] could find.”

Referring to what he calls “the great cat debates,” Gill writes: “I claim no great expertise or authority… now or in the ancient histories of early textbook editions.”

Fair enough. Writing, editing, and revising multiple editions of Ornithology was an enormous undertaking—one for which Gill deserves much credit. But there was, available at the time, work by scientists who, unlike Stallcup actually studied predation. Indeed, even before the first edition of Ornithology was published, a great deal of work had been done—and compiled in the first edition (published in 1988) of The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour. In it, Mike Fitzgerald, one of the world’s foremost experts on the subject, reviewed 61 predation studies, concluding:

“Predation on songbirds by domestic cats is noticed because it takes place during the day, whereas much predation on mammals takes place at night. People generally enjoy having songbirds in their gardens, and providing food in winter may increase the numbers of birds. When cats kill some of these birds, people assume that cats are reducing the bird populations. However, although this predation is so visible, and unpopular, remarkably little attempt has been made to assess its impact on populations of songbirds.” [7]

Two years later, Fitzgerald had a brief letter on the subject published in Environmental Conservation. His comments are as relevant today as they were some 21 years ago:

“Before embarking… on programmes to educate the public so that they will pressure elected officials to act on ‘cat delinquency,’ we must discover what effect domestic cats really have on the wildlife populations in various urban localities—not merely what effect we assume they have on the basis of prey brought home by cats in one English village. Although we know what prey cats bring home in a few urban localities, we do not know what effect this predation has on the prey populations, or how the wildlife populations might differ if cat populations were reduced. Until we have this information we cannot ensure sound educational programmes. We should perhaps also try to discover what values urban people place on their wildlife and their pets—it seems likely that many of the people who love their pets also treasure the wildlife.” [8]

Surely, Fitzgerald’s work would have been more appropriate for, and useful to, Ornithology’s audience. Instead, unsuspecting undergraduates were treated to biased editorializing dressed up as science.

Third Edition

Gill tells me I wasn’t the first to “react… to the Stallcup paper,” and that the push-back was sufficient to prompt its removal from the third edition. Gone, too, is Banks’ report. Instead, Gill employs the now-common kitchen-sink approach, rattling off a litany of sins—borrowed, it seems, from the American Bird Conservancy.

“Domestic house cats in North America, for example, may kill hundreds of millions of songbirds each year. Farmland and barnyard cats kill roughly 39 million birds (and lots of mice, too) each year. Millions of hungrier, feral (wild) cats add to this toll. There is a common-sense solution. Letting cats roam outside the house shortens their expected life span from 12.5 years to 2.5 years and increases their risk of rabies, distemper, toxoplasmosis, and parasites. Evidence is mounting that cats help to spread diseases such as Asian bird flu. The message is clear: Keep pet cats inside for their own well being and for the future of backyard birds (http://www.abcbirds.org/cats/).” [9]

That 39 million birds figure, of course, comes from the infamous “Wisconsin Study,” the authors of which claim: “The most reasonable estimates indicate that 39 million birds are killed in the state each year.” [10] (The “reason” is, in fact, notably absent from Coleman and Temple’s figure—which can be traced to “a single free-ranging Siamese cat” that frequented a rural residential property in New Kent County, Virginia. [11])

Its implied use as a nationwide estimate, Gill says, was “a lapse.” The more serious lapse by far, though—not in copyediting but in judgment—is Gill’s endorsement of ABC.

A Constructive Approach

While he readily admits that he’s “not tracked nor verified [ABC’s] stats (and have paid precious little attention to the issue for almost 10 years),” Gill’s support is unwavering.

“ABC has taken a lead role on the cat-bird issues, generally with a constructive approach, which I applaud, given how polarized the debates can be.”

Constructive? As I’ve pointed out repeatedly, no organization has been more effective at working the anti-TNR pseudoscience into a message neatly packaged for the mainstream media, and eventual consumption by the general public. (The Wildlife Society, though, which shares ABC’s penchant for bumper-sticker science and public discourse via sound-bites, is at least as eager to participate in the witch-hunt.)

Among the more glaring examples: senior policy advisor, Steve Holmer’s claim, quoted in the Los Angeles Times, that “there are about… 160 million feral cats [nationwide]” [12]; ABC’s promotion of “Feral Cats and Their Management,” with its absurd $17B economic impact “estimate,” published last year by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; and the numerous errors, exaggerations, and misrepresentations that persist in their brochure Domestic Cat Predation On Birds and Other Wildlife (PDF)—including a rather significant blunder that Ellen Perry Berkeley brought to light seven years ago in her book TNR Past, Present and Future. [13]

A constructive approach begins, by necessity, with sound science. But when it comes to the issue of free-roaming cats, at least, ABC has demonstrated neither an interest nor an aptitude.

So how does such an organization end up as the sole resource listed in a widely-used undergraduate textbook? (One written by the same man who served as the National Audubon Society’s chief scientist from 1996 to 2005, no less.) What’s next—physiology and nutrition books directing students to the PepsiCo Website for their hydration lesson? Psychology texts deferring to Pfizer (makers of Zoloft) on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors?

Frank Gill’s View

Gill never responded to my follow-up questions for this post. Still, his comments during our first exchange shed some light on his general attitude toward cats. “I have owned some wonderful (Siamese) cats in my life,” Gill explained, “so I do view them positively in many ways. But when they are dumped near a research station by returning vacationers and then eat the ringed birds I have been studying for many years, I take a different view.”

He followed this last sentence with a smiley-face emoticon, though the joke was clearly wasted on me.

“My informal view now is that managed feral cat colonies are potentially a serious threat to local bird populations, including both migrants that stopover in urban parks and endangered shorebird colonies. Sustaining those colonies should be prohibited generally. The return of coyotes to suburban landscapes is most welcome both to add a top predator to these ecosystems and to counter the numbers of feral cats as well as other midsized predators that impact breeding productivity. Just their presence in a neighborhood should persuade cat owners to keep their cats safely inside!”

• • •

It would be a mistake to suggest that the sloppy, flawed research I spend so much time critiquing can be traced directly to the second or third editions of Frank Gill’s textbook. Still, for many students, the path to a degree in ornithology (and onto related graduate degrees) leads through the book of the same name. As such, Ornithology may well be their first exposure to issues of population dynamics, conservation, and the like.

First impressions tend to be lasting ones. If, as a wide-eyed undergraduate, you “learned” that cats kill up to four million songbirds every day, how might that shape your future studies? Your career? What if you “learned” that such predation takes a $17B toll on the country annually?

Considering the tremendous burden we’re placing on future generations, why would we hobble them—before they even get started, really—with such misinformation and bias? They’ve got more than enough on their plate without having to fact-check their textbooks, too.

Literature Cited

1. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 1st ed. 1990, New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. 660.

2. Banks, R.C., Special Scientific Report—Wildlife No. 215. 1979, United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service: Washington, DC. p. 16.

3. Stallcup, R., “A reversible catastrophe.” Observer 91. 1991(Spring/Summer): p. 8–9. http://www.prbo.org/cms/print.php?mid=530

http://www.prbo.org/cms/docs/observer/focus/focus29cats1991.pdf

4. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 2nd ed. 1995, New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

5. Perry, G. Cats—perceptions and misconceptions: Two recent studies about cats and how people see them. in Urban Animal Management Conference. 1999.

6. Millwood, J. and Heaton, T. The metropolitan domestic cat. in Urban Animal Management Conference. 1994.

7. Fitzgerald, B.M., Diet of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York. p. 123–147.

8. Fitzgerald, B.M., “Is Cat Control Needed to Protect Urban Wildlife?“ Environmental Conservation. 1990. 17(02): p. 168-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900031970

9. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 3rd ed. 2007, New York: W.H. Freeman. xxvi, 758 p.

10. Coleman, J.S., Temple, S.A., and Craven, S.R., “Cats and Wildlife: A Conservation Dilemma.” 1997. http://forestandwildlifeecology.wisc.edu/wl_extension/catfly3.htm

11. Mitchell, J.C. and Beck, R.A., “Free-Ranging Domestic Cat Predation on Native Vertebrates in Rural and Urban Virginia.” Virginia Journal of Science. 1992. 43(1B): p. 197–207. www.vacadsci.org/vjsArchives/v43/43-1B/43-197.pdf

12. Yoshino, K. (2010, January 17). A catfight over neutering program. Los Angeles Times, from http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-feral-cats17-2010jan17,0,1225635.story

13. Berkeley, E.P., TNR Past present and future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement. 2004, Bethesda, MD: Alley Cat Allies.