“Evidence continues to pile up,” writes Michael Hutchins, Executive Director and CEO of The Wildlife Society, in yesterday’s blog post, “that Toxoplasmosis, a disease caused by a parasite (Toxoplasma gondii) that lives in the guts of cats, may be responsible for serious human health problems.”

Hutchins was referring to a recent study in which researchers found “Infection with T. gondii was associated with a 1.8-fold increase in the risk of brain cancers across the range of T. gondii prevalence in our dataset (4–67 percent).” [1]

True to form, Hutchins used the opportunity to call for “doing away with managed cat colonies and TNR (trap-neuter-release) management practices for feral cats,” making a public plea to “public health officials, including the CDC.”

But what exactly does this latest study contribute to Hutchins’ “pile of evidence”?

The Study

According to a news release from the U.S. Geological Survey, “the study analyzed 37 countries for several population factors” and “showed that countries where Toxoplasma gondii is common also had higher incidences of adult brain cancers than in those countries where the organism is not common.”

“The study does not prove that Toxoplasma gondii directly causes cancer in humans, and the study does not imply that an infected person automatically has high cancer risk,” says [Kevin] Lafferty, who is based at the USGS Western Ecological Research Center. “However, we do know that Toxoplasma gondii behaves in ways that could stimulate cells towards cancerous states, so the discovery of this correlation offers a new hypothesis for an infectious link to cancer.”

According to the study’s abstract (I’ve been unable to access the paper), the authors took into account several factors:

“We corrected reports of incidence for national gross domestic product because wealth probably increases the ability to detect cancer. We also included gender, cell phone use and latitude as variables in our initial models. Prevalence of T. gondii explained 19 per cent of the residual variance in brain cancer incidence after controlling for the positive effects of gross domestic product and latitude among nations.” [1]

It will be interesting to compare—once I’m able to review the study in detail—these findings with those published earlier this year in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute (a collaborative effort involving several agencies, including, as it happens, the CDC):

“The relatively low variation in incidence and death rates for cancer of the brain and [other nervous system] nationally and internationally suggests that environmental risk factors do not play a major role in this disease. In fact, other than hereditary tumor syndromes and increased familial risk without a known syndrome, the only known modifiable causal risk factor for brain tumors is exposure to ionizing radiation.” [2, in-line citations removed for readability]

Correlation ≠ Causation

To illustrate the critical difference between correlation and causation, author Charles Seife uses the dramatic example of the mid-1990s NutraSweet scare—which, incredibly, was also linked brain cancer (falsely, as it turns out).

“Lots of people… don’t eat foods that contain the artificial sweetener NutraSweet for fear of developing brain cancer,” writes Seife, tracing the mythical connection to “a bunch of psychiatrists led by Washington University’s John Olney.”

“These scientists noticed that there was an alarming rise in brain tumor rates about three or four years after NutraSweet was introduced in the market.

Aha! The psychiatrists quickly came to the obvious conclusion: NutraSweet is causing brain cancer! They published their findings in a peer-reviewed journal, the Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, and their paper immediately grabbed headlines around the world.

But a closer look at the data shows how unconvincing the link really is. Sure, NutraSweet consumption was going up at the same time brain tumor rates were, but a lot of other things were on the rise, too, such as cable TV, Sony Walkmen, Tom Cruise’s career. When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, government spending increased just as dramatically as brain tumor rates… The correlation between government overspending and brain cancer is just as solid as the link between NutraSweet and brain cancer.” [3]

Sounds eerily familiar, doesn’t it?

Given the numerous factors and interrelationships involved in developing brain cancer—some of which, of course, we don’t even know—Hutchins’ eager indictment of cats is, at the very least, premature. In fact, Hutchins is going to have a difficult time connecting the dots in light of recent research.

More Cats, Less Brain Cancer

If brain cancer is more common where T. gondii is more common, then one might expect rates of brain cancer to increase over time as the prevalence of T. gondii increases. Which would seem to be the case here in the U.S., if cats are indeed the culprit.

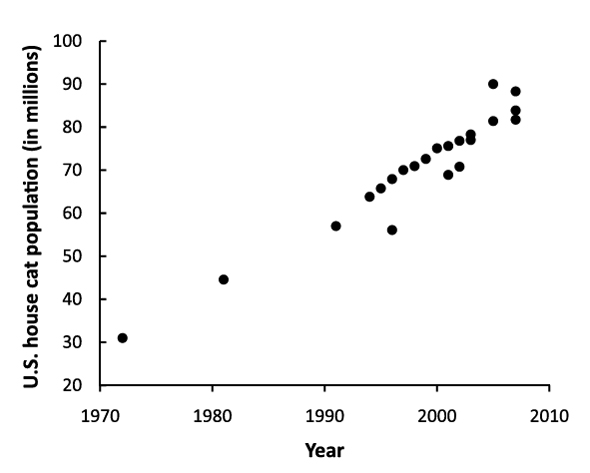

According to data compiled last year in Conservation Biology, the population of pet cats tripled over the past 40 years, from approximately 31 million in 1971 to more than 90 million today. [4]

So what about brain cancer?

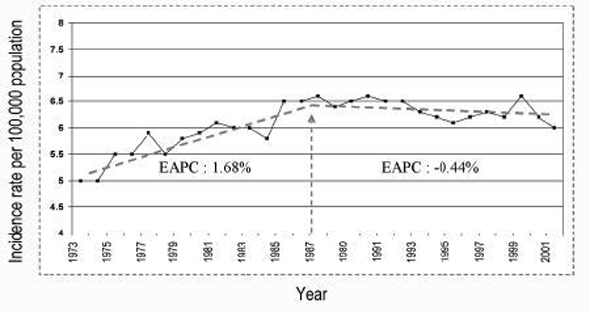

In 2006, researchers using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program for 1973–2001 were surprised to find incident rates decreasing. Following an increase of 1.68 percent between 1973 and 1987, the incident rate began to drop off by 0.44 percent annually (as indicated in the chart below; EAPC = estimated annual percentage of change).

“The cause for this decline,” suggest the study’s authors, “is unclear because of the paucity of definitive knowledge on the risk factors of brain cancer, but solace can be taken from the fact that brain cancers are not rising in this era of increasing environmental toxic exposures.” [5]

More recently, a report published by the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (PDF) found “no statistically significant trend in incidence rates of all primary brain tumors from 2004 through 2007.” [6]

• • •

Lafferty and his colleagues concede that their work is “correlational,” a jumping-off point for further investigation. Again, I haven’t been able to read the paper yet, but I’m skeptical that their line of inquiry is headed anywhere productive. Cast a net as wide as they did—surveying the prevalence of T. gondii and incidence of brain cancer across 37 countries—and you’re bound to catch something.

Of course, something is all Michael Hutchins needs for his witch-hunt.

Hutchins refers to piles of evidence without taking the trouble to examine any of it, simply ignoring what doesn’t fit neatly into his narrative—declining brain cancer rates in the U.S., for example. Or, some rather interesting comments from Lafferty himself (which, strangely, were omitted from USGS’s news release, but were mentioned by several other news outlets, including LiveScience and Fox News):

“…one shouldn’t be panicking about owning cats… The risk factors for getting Toxoplasma are really hygiene and eating undercooked meat. One should be more concerned about those than pets.”

That sounds familiar, too. It’s the same advice the CDC provides on its Website.

Literature Cited

1. Thomas, F., et al., “Incidence of adult brain cancers is higher in countries where the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii is common.” Biology Letters. 2011.

2. Kohler, B.A., et al., “Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975, Featuring Tumors of the Brain and Other Nervous System.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011. http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/03/31/jnci.djr077.abstract

3. Seife, C., Proofiness: The Dark Arts of Mathematical Deception. 2010: Viking Adult.

4. Lepczyk, C.A., et al., “What Conservation Biologists Can Do to Counter Trap-Neuter-Return: Response to Longcore et al.” Conservation Biology. 2010. 24(2): p. 627–629. www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/pdf/Lepczyk-2010-Conservation%2520Biology.pdf

5. Deorah, S., et al., “Trends in brain cancer incidence and survival in the United States: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, 1973 to 2001.” Neurological Focus. 2006. 20(April): p. E1. thejns.org/doi/pdf/10.3171/foc.2006.20.4.E1

6. n.a., CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2004-2007. 2011, Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States: Hinsdale, IL. www.cbtrus.org/2011-NPCR-SEER/WEB-0407-Report-3-3-2011.pdf