Mother Jones, according to its Website, “is a nonprofit news organization that specializes in investigative, political, and social justice reporting.”

“…smart, fearless journalism” keeps people informed—“informed” being pretty much indispensable to a democracy that actually works. Because we’ve been ahead of the curve time and again. Because this is journalism not funded by or beholden to corporations. Because we bust bullshit and get results. Because we’re expanding our investigative coverage while the rest of the media are contracting. Because you can count on us to take no prisoners, cleave to no dogma, and tell it like it is. Plus we’re pretty damn fun.

Right up my alley. Until now.

With “Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!,” published in the July/August issue, articles editor Kiera Butler fails rather magnificently all the way around.

(The article isn’t available directly from MotherJones.com yet, but you can read it (print it, too) simply by signing up for the magazine’s e-mail updates. Enter your e-mail address and click “Sign Up.” In the next window, click on “ACCESS THE ISSUE NOW”—the full issue will then open automatically in Zinio, a digital magazine reader. “Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!” begins on p. 72.)

The title, by the way, comes from a 1965 cult classic in which “Three strippers seeking thrills encounter a young couple in the desert.” Sadly, the film is a better reflection of reality than the information in Butler’s article is.

Population of Cats

The most obvious blunder: Citing what seems to be the same data set (“the US feline population has tripled over the last four decades”) I referred to in my “Spoiler Alert” post, Butler arrives not at 90 million or so, as indicated in the original source [1], or even the bogus 150 million figure the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Tom Will tried to sell last year to the Bird Conservation Alliance.

No—according to Butler, there were 600 million cats in this country in 2007.

At that time, the human population was 301.3 million. For the sake of easy math, then, let’s call it two cats for every human (talk about “hip-deep in cats”!). This, I believe, sets a new record for absurd population claims—far surpassing the previous record held by Steve Holmer, senior policy advisor for the American Bird Conservancy.

And from here, it only gets worse. While her grossly inflated population figure might be attributed a simple mistake. These things happen (though, of course, one expects such things to be caught by somebody on the editorial staff). However, the misinformation, misrepresentations, and missteps that make up the bulk of “Faster, Pussycat!” betray either willful ignorance or glaring bias. Or both.

Smart, fearless journalism it is not.

One Billion Birds

Butler’s litany of complaints against feral cats is all too familiar: wildlife impacts (birds, in particular), public health threats, the “failures” of TNR, the powerful feral cat lobby, and the emotional/irrational nature of feral cat advocates (i.e., the classic “crazy cat lady” label). Her sources, too, include all the usual suspects; though few are cited, many others are obvious.

Sources of Mortality

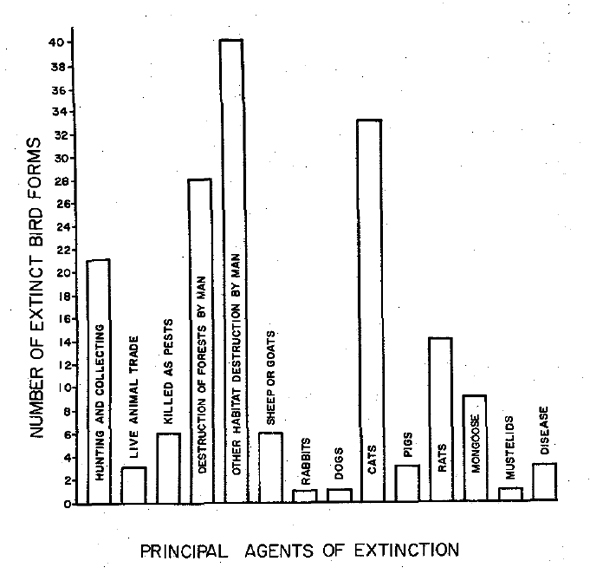

Butler claims that domestic cats (“officially considered an invasive species”) top the list of mortality sources, killing perhaps one billion birds annually in the U.S. (Her tabulated comparison of seven mortality sources bears the familiar title “Apocalypse Meow.”)

The source of Butler’s “highest reliable estimates” is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, though the one-billion-birds claim has been made by others, including Nico Dauphine and Robert Cooper, [2, 3] and Rich Stallcup. [4] (In fact, Dauphine refers specifically to Stallcup’s wild-ass guess back-of-the-envelope calculation in her infamous “Apocalypse Meow” presentation.)

Yet even ABC, never one to go easy on cats—or to let science get in the way of their message—ranks building collisions ahead of cats. (Interestingly, neither USFWS nor ABC mentions the most direct human-caused source of bird mortality—hunting—which may account for 120 million avian deaths annually in the U.S. [5])

The one-billion-birds claim hinges upon an inflated estimate of outdoor cats (Dauphine and Cooper, for example, ignore published survey results [6–8], in effect doubling the number of pet cats allowed outdoors) and inflated predation rates (typically extrapolated from small, flawed studies). Multiplying one by the other, the result is impressive (hence, it’s “stickiness”).

Unfortunately, it’s also meaningless.

Still, such aggregate figures are useful for providing a scientific veneer to what is, at its core, little more than a witch-hunt. All of which makes it an easier sell to the media and the general public.

But sound bites ignore the importance of context. Aggregate predation rates, for example, fail to differentiate across vastly different habitats (e.g., islands, forests, coastlines, etc.), species (e.g., songbirds, seabirds, etc.), conditions (e.g., sick and healthy, young and old, etc.), and levels of vulnerability (e.g., ground-nesting and cavity-nesting species, rare and common species, etc.).

Predators—cats included—catch what’s easy. Indeed, at least two studies [9, 10] have found that cat-killed birds tend to be less healthy than those killed in non-predatory events (e.g., the other six mortality sources shown in Butler’s table).

Island Extinctions

In asserting that cats are “responsible for at least 33 avian extinctions worldwide,” Butler overlooks or ignores a critical detail: those extinctions involve primarily—perhaps exclusively—island species, with “insular endemic landbirds [being] most frequently driven to extinction” [11] And even this point is a matter of some debate. “Birds (both landbirds and seabirds) have been affected most by the introduction of cats to islands,” writes Mike Fitzgerald, one of the world’s foremost experts on the subject, “but the impact is rarely well documented.” [12]

“In many cases the bird populations were not well described before the cats were established and the possible role of other factors in changes in the bird populations are treated inadequately.” [12]

So what’s the impact of cats on continents?

In 2000, Fitzgerald and co-author Dennis Turner published a review of 61 predation studies, concluding unambiguously: “there are few, if any studies apart from island ones that actually demonstrate that cats have reduced bird populations.” [13]

Catbird Mortalities

Referring to research conducted by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center’s Peter Marra, Butler contends that “cats caused 79 percent of deaths of juvenile catbirds in the suburbs of Washington, DC.” In fact, Marra and his colleagues documented just six deaths attributable to cats, of 42 overall (then justified another three on dubious grounds). [14]

That 79 percent figure comes from dividing the number of deaths attributed to all sources of predation (33) by the total number of deaths documented over the course of the study (42). Butler’s misreading overstates predation by cats by more than 500 percent.

Public Health Threats

“Feral cats,” writes Butler, “can carry some heinous people diseases, including rabies, hookworm, and toxoplasmosis, and infection known to cause miscarriages and birth defects.” Her omission of infection rates—remarkably low in light of the frequent contact between humans and cats—suggests an interest more in fear-mongering than anything else.

Hookworms

A hookworm outbreak in the Miami Beach area in late 2010 made headlines, prompting officials to create a “cat poop map” (cats can pass hookworm eggs in their feces).

Meanwhile, Floridians were dying of influenza or pneumonia by the hundreds. In fact, according to the Florida Department of Health, 100–140 or so die each week during the winter months. (Actually, that figure accounts for only 24 of the state’s 67 counties, so the total is likely much higher.)

My point is not to dismiss the risk of “heinous people diseases” (or the suffering of those who become infected) but to put that risk into perspective. (In terms of public health, we’re better off focusing on frequent hand washing, sneezing into our sleeves, and, in the case of hookworms on the beach, wearing flip-flops—as opposed to, say, exterminating this country’s most popular companion animal by the millions.)

Toxoplasmosis

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Website, “Although cats can carry diseases and pass them to people, you are not likely to get sick from touching or owning a cat.” And, notes the CDC, “People are probably more likely to get toxoplasmosis from gardening or eating raw meat than from having a pet cat.”

(The same is true of feeding feral cats, by the way. While it’s true that their infection rates tend to be higher, [15] our frequent, close contact with pet cats more than offsets these differences.)

TNR

“In theory,” writes Butler, “TNR sounds great. If cats can’t reproduce, their population will decline gradually. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work. To put a dent in the total number of cats, at least 71 percent of them must be fixed, and they are notoriously hard to catch.”

In Los Angeles, adds Butler, “it failed miserably in the past.”

Contrary to Butler’s claims, however, there are numerous well-documented examples of TNR programs reducing colony size.

Perhaps the best-known TNR success story in this country is ORCAT. As of 2004, ORCAT, run by the Ocean Reef Community Association, had reduced its “overall population from approximately 2,000 cats to 500 cats.” [16] According to the ORCAT Website, the population today is approximately 350, of which only about 250 are free-roaming.

Other examples include a TNR program on the campus of the University of Florida University of Central Florida,

Orlando, in which caretakers found homes for more than 47 percent of the campus’ socialized cats and kittens, helping them reduce the campus cat population more than 66 percent, from 68 to 23. [17]

In North Carolina, researchers observed a 36 percent average decrease among six sterilized colonies in the first two years (even in the absence of adoptions), while three unsterilized colonies experienced an average 47 percent increase. [18] Four- and seven-year follow-up censuses revealed further reductions among sterilized colonies. [19]

A survey of caretakers in Rome revealed a 22 percent decrease overall in the number of cats through TNR, despite a 21 percent rate of “cat immigration.” [20]

And in South Africa, researchers recommended that “a suitable and ongoing sterilization programme, which is run in conjunction with a feral cat feeding programme, needs to be implemented” [21] on the campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Howard College—despite its proximity to “conservation-sensitive natural bush habitat and a nature reserve on the northern border.” [22]

The Cost of TNR

“Cash-strapped cities,” argues Butler, “can’t afford to chase down, trap, and sterilize every stray—a process that costs $100 per kitty.” So, can these cities afford to round up and kill the cats?

Mark Kumpf, past president of the National Animal Control Association doesn’t think so. “There’s no department that I’m aware of,” says Kumpf, “that has enough money in their budget to simply practice the old capture-and-euthanize policy; nature just keeps having more kittens.” Traditional control methods, he says, are akin to “bailing the ocean with a thimble.” [23]

The Cat Lobby

If TNR is so ineffective, why is it becoming the feral cat management approach of choice across the country (adopted in “at least 10 major cities,” according to Butler)? It must be the powerful cat lobby.

Alley Cat Allies, “whose budget was $5.3 million last year,” writes Butler, “has enjoyed generous grants from cat-food venders like PetSmart and Petco.”

It’s a play straight out of Dauphine’s playbook: paint the avian-industrial complex TNR opponents as victims of the powerful cat lobby. (In The Wildlife Professional’s recent special issue, “The Impact of Free Ranging Cats,” Dauphine complains: “The promotion of TNR is big business, with such large amounts of money in play that conservation scientists opposing TNR can’t begin to compete.” [24])

Alley Cat Allies

How generous were these grants, exactly? According to ACA’s 2010 Annual Report (PDF):

“Alley Cat Allies received more than $5.2 million in support between August 1, 2009 and July 31, 2010: more than 69,000 individuals contributed $4.8 million, including over $1 million in bequests. An additional $245,000 came from Workplace Campaigns, and over $14,000 came from foundation grants.”

Roughly 0.2 percent of their “total public support” came from all foundations combined. In 2009, grants and foundations accounted for 1.7 percent; in 2008, 1.0 percent. (Maybe Butler never got the memo re: MoJo’s commitment to bullshit-busting.)

New Jersey Audubon

Another of Dauphine’s complaints that found its way into “Faster, Pussycat!”:

“Pro-feral groups—there are 250 or so in the United States—have used their financial might to woo wildlife groups. Audubon’s New Jersey chapter backed off on its opposition to TNR in 2005, around the same time major foundations gave the chapter grants to partner with pro-TNR groups.”

What Butler (like Dauphine before her) fails to acknowledge is the important role NJAS plays in the New Jersey Feral Cat & Wildlife Coalition, which has developed a set of model protocols and ordinances designed to help municipal TNR programs in ensuring the protection of any vulnerable native wildlife (DOC).

This is exactly the kind of collaborative effort that should be supported.

For what it’s worth: it’s not clear that NJAS was easily wooed with grant funding. A quick visit to Guidestar.com reveals that NJAS brought in $6.8 million in 2008, and had $25.6 million in “net assets or fund balances” on its books. (I’ve been unable to determine the amount of grant funding NJAS received for “this important initiative,” as CEO and VP of Conservation and Stewardship Eric Stiles described it in a 2008 newsletter. [25])

Mental Health

Butler frames the TNR debate using what’s come to be standard form: rationale scientists on one side; on the other, cat advocates fueled by emotion. And mental illness, too, apparently: “There’s also speculation that [toxoplasmosis] can trigger schizophrenia and even the desire to be around cats—some researchers blame the crazy-cat-lady phenomenon on toxo.”

A Heated Debate

It’s a dangerous combination, according to Butler.

“Many of the biologists I spoke with say they’ve been harassed and even physically threatened when they’ve presented research about the effect cats have on wildlife.”

Is it really so one-sided?

Why didn’t Butler mention the case of Jim Stevenson, the Galveston birder who, in 2006, shot and killed (though not immediately) a feral cat within earshot of the cat’s caretaker? [26]

Or, more recently, the charges of attempted animal cruelty filed by the Washington Humane Society against Dauphine? (Or, for that matter, the stream of toxic comments almost guaranteed to accompany nearly any online story about feral cats or TNR.)

Clearly, the “cat people” don’t have a monopoly on emotional—even violent—responses to the issue.

Sustaining a Killer

When Butler tells an ecologist she knows that she’s feeding a feral cat, she’s told: “Basically, you’re sustaining a killer.” Which is essentially Butler’s intended take-away:

“Until they do [invent a single-dose sterilization drug], biologists recommend a combination of strategies. For starters, quit feeding ferals: Beyond sustaining strays, the practice often leads to delinquent pet owners to abandon their cats outdoors, assuming they will be well cared for.”

Are we to believe that abandonment is reduced or eliminated where the feeding of feral cats is prohibited? Owners (delinquent, I agree) interested in dumping their cats can, unfortunately, do so easily.

The far greater incentive for dumping comes from local shelters, most of which euthanize kill the majority of cats brought in. Many require a surrender fee.

I’m just about the last person to defend the dumping of cats, but shouldn’t we acknowledge the aspects of “animal control” policy that contribute to it?

But back to this idea that “no food” means “no ferals.” It sounds reasonable enough, but doesn’t hold up very well to scrutiny. For one thing, where there are humans, there’s food to be found. In fact, even where there are no people, cats don’t starve.

On Marion Island—barren and uninhabited—it took 19 years to eradicate approximately 2,200 cats. Their only human provision: “the carcasses of 12,000 day-old chickens” each injected with the poison sodium monofluoroacetate. [27] (The rest—the vast majority—were killed through the introduction of feline distemper, intensive hunting and trapping, and dogs. [28, 27])

Is Butler suggesting that the cats in her neighborhood would have it tougher than the Marion Island cats? Even setting aside the cruelty involved, we’re not likely to starve our way out of the “feral cat problem.” Unlike TNR, such an approach only drives the cats (and their caretakers) underground.

This, of course, is roughly the same approach that’s proved ineffective failed so spectacularly at addressing so many other complex issues, including drug enforcement, immigration policy, gays in the military, and so forth.

• • •

Since I launched Vox Felina last year, I’ve been critical of articles appearing in any number of publications: scientific journals (e.g., Conservation Biology), major newspapers (e.g., The Washington Post and The New York Times), an alt-weekly, and more.

None of which bothered me in the least, as I feel no particular connection to any of them. This is not to say that I don’t value, admire, and respect much of the work found, for instance, in the Times—only that I’ve no affinity for, or loyalty to, the paper itself.

But Mother Jones is different. Maybe it’s that whole bullshit-busting, take-no-prisoners, tell-it-like-it-is business—I’d like to think that’s something we share in common.

This time around, though, the magazine served up bullshit by the shovelful, swallowed in one gulp the misinformation churned out by ABC, The Wildlife Society, and other TNR opponents, and… well, told it like it isn’t.

With the publication of “Faster, Pussycat!,” Mother Jones failed miserably in its promise to readers. Which, I have to think, isn’t a lot of fun.

Literature Cited

1. Lepczyk, C.A., et al., “What Conservation Biologists Can Do to Counter Trap-Neuter-Return: Response to Longcore et al.” Conservation Biology. 2010. 24(2): p. 627–629. www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/pdf/Lepczyk-2010-Conservation%2520Biology.pdf

2. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2009. p. 205–219. http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/pif/pubs/McAllenProc/articles/PIF09_Anthropogenic%20Impacts/Dauphine_1_PIF09.pdf

3. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., “Pick One: Outdoor Cats or Conservation.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 50–56.

4. Stallcup, R., “A reversible catastrophe.” Observer 91. 1991(Spring/Summer): p. 8–9. http://www.prbo.org/cms/print.php?mid=530

http://www.prbo.org/cms/docs/observer/focus/focus29cats1991.pdf

5. Klem, D., “Glass: A Deadly Conservation Issue for Birds.” Bird Observer. 2006. 2. p. 73–81. http://www.massbird.org/BirdObserver/index.htm

6. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.1541

7. Lord, L.K., “Attitudes toward and perceptions of free-roaming cats among individuals living in Ohio.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2008. 232(8): p. 1159-1167. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_232_8_1159.pdf

8. APPA, 2009–2010 APPA National Pet Owners Survey. 2009, American Pet Products Association: Greenwich, CT. http://www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp

9. Møller, A.P. and Erritzøe, J., “Predation against birds with low immunocompetence.” Oecologia. 2000. 122(4): p. 500–504. http://www.springerlink.com/content/ghnny9mcv016ljd8/

10. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: Is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86–99. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bsc/ibi/2008/00000150/A00101s1/art00008

11. Nogales, M., et al., “A Review of Feral Cat Eradication on Islands.” Conservation Biology. 2004. 18(2): p. 310–319. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00442.x/abstract

12. Fitzgerald, B.M., Diet of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York. p. 123–147.

13. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

14. Balogh, A., Ryder, T., and Marra, P., “Population demography of Gray Catbirds in the suburban matrix: sources, sinks and domestic cats.” Journal of Ornithology. 2011: p. 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0648-7

http://nationalzoo.si.edu/scbi/migratorybirds/science_article/pdfs/55.pdf

15. Dubey, J.P. and Jones, J.L., “Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and animals in the United States.” International Journal for Parasitology. 2008. 38(11): p. 1257–1278. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6T7F-4S85DPK-1/2/2a1f9e590e7c7ec35d1072e06b2fa99d

16. Levy, J.K. and Crawford, P.C., “Humane strategies for controlling feral cat populations.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1354–1360. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/default.asp

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1354.pdf

17. Levy, J.K., Gale, D.W., and Gale, L.A., “Evaluation of the effect of a long-term trap-neuter-return and adoption program on a free-roaming cat population.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(1): p. 42-46. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.42

18. Stoskopf, M.K. and Nutter, F.B., “Analyzing approaches to feral cat management—one size does not fit all.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1361–1364. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552309

www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1361.pdf

19. Nutter, F.B., Evaluation of a Trap-Neuter-Return Management Program for Feral Cat Colonies: Population Dynamics, Home Ranges, and Potentially Zoonotic Diseases, in Comparative Biomedical Department. 2005, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC. p. 224. http://www.carnivoreconservation.org/files/thesis/nutter_2005_phd.pdf

20. Natoli, E., et al., “Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy).” Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2006. 77(3-4): p. 180–185. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TBK-4M33VSW-1/2/0abfc80f245ab50e602f93060f88e6f9

www.kiccc.org.au/pics/FeralCatsRome2006.pdf

21. Tennent, J., Downs, C.T., and Bodasing, M., “Management Recommendations for Feral Cat (Felis catus) Populations Within an Urban Conservancy in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.” South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 2009. 39(2): p. 137–142. http://dx.doi.org/10.3957/056.039.0211

22. Tennent, J. and Downs, C.T., “Abundance and home ranges of feral cats in an urban conservancy where there is supplemental feeding: A case study from South Africa.” African Zoology. 2008. 2: p. 218–229. http://login.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eih&AN=47391224&site=ehost-live

23. Hettinger, J., “Taking a Broader View of Cats in the Community.” Animal Sheltering. 2008. September/October. p. 8–9. http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/taking_a_broader_view_of_cats.html

http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/broader_view_of_cats.pdf

24. Dauphine, N., “Follow the Money: The Economics of TNR Advocacy.” The Wildlife Professional. 2011. 5(1): p. 54.

25. Stiles, E., NJAS Works with Coalition to Reduce Bird Mortality from Outdoor Cats. 2008, New Jersey Audubon Society. http://www.njaudubon.org/Portals/10/Conservation/PDF/ConsReportSpring08.pdf

26. Barcott, B. (2007, December 2, 2007). Kill the Cat That Kills the Bird? New York Times, from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/02/magazine/02cats-v–birds-t.html

27. Bester, M.N., et al., “A review of the successful eradication of feral cats from sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Southern Indian Ocean.” South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 2002. 32(1): p. 65–73.

http://www.ceru.up.ac.za/downloads/A_review_successful_eradication_feralcats.pdf

28. Bloomer, J.P. and Bester, M.N., “Control of feral cats on sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Indian Ocean.” Biological Conservation. 1992. 60(3): p. 211-219. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6V5X-48XKBM6-T0/2/06492dd3a022e4a4f9e437a943dd1d8b