Relative to other studies of the domestic cat’s predatory habits, Carol Fiore’s 2000 thesis work is cited only occasionally in the literature. [1, 2] Indeed, it might easily go unnoticed were it not for its inclusion in the American Bird Conservancy’s brochure Domestic Cat Predation on Birds and Other Wildlife, and the fact that Fiore posted a summary of the study on her website—making much of its content available to anybody interested in the topic.

Fiore’s “primary goal,” she writes, “was to estimate the number of cats in Wichita, the average number of birds killed per cat and the total number of birds killed by cats each year.” [3] In fact, there was more to it than that.

Fiore was also trying to quantify the number of birds killed by cats without their owners’ knowledge, thereby addressing a concern frequently expressed by researchers whose predation estimates rely on prey records kept by cat owners. [4–7] In other words, how many birds were being killed by cats, really?

Fiore’s thesis project was an ambitious undertaking—perhaps too ambitious. Although her goal was admirable, her small sample size, flawed analytical methods, and various confounding factors cast considerable doubt over her findings. In addition, Fiore’s thesis document is peppered with evidence of bias. Indeed, she raises questions about her motivation for the project (and underlying assumptions) when, early on, she refers uncritically to the ABC’s Cats Indoors! campaign and the Wisconsin Study, and mischaracterizes the work of William George (see Note 1).

I’m afraid that, in the end, Fiore’s work does little to enhance our understanding of the domestic cat’s hunting behavior. In fact, because her conclusions tend to misrepresent the study’s findings, Fiore actually does more to perpetuate the mythology surrounding predation than the science.

The Study

Fiore’s research incorporated several methods, each intended to provide a key piece of the predation puzzle:

- Twenty-eight Wichita, Kansas cat owners were recruited and asked to record the number and, when possible, also the species, of birds killed by their 41 cats over the period of approximately one year.

- Some of these same participants were asked to collect scat samples, which were then analyzed for feathers. Detection of feathers was used to account for kills not reported by cat owners.

- The behavior of eight participating cats was observed with the help of radio collars.

- Cat density in the area was estimated by combining telephone survey results (regarding the proportion of area cats that received the rabies vaccine) with information from local veterinarians (regarding the yearly total of rabies vaccines administered to cats).

- Using Christmas Bird Count data, the density of Northern Cardinals in the Wichita area was estimated.

- The impact of free-roaming cats on the population of cardinals was then estimated by combining findings from each of the investigations described above (with the exception of the radio collar monitoring).

- A second telephone survey was conducted, this time to learn about residents’ attitudes concerning possible cat regulations (e.g., leash laws, licensing, etc.).

Birds Brought Home by Cats

Twenty-nine (71%) of the cats were reported to have killed birds during the study period, while 12 (29%) were credited with no kills. (These figures would later be adjusted based on the results of the scat analysis, as described below.) However, multi-cat households posed a particular problem. “For owners with more than one cat,” writes Fiore, “kills were alternated between cats if the owner was unsure of the cat responsible.” [3]

As a result of her “alternating attribution” (my term, not Fiore’s) method, it’s possible that five cats were incorrectly included among the hunters (see Note 2 for details). If so, the proportion of hunters was not 71%, but 61%.

Other Studies

Either way, Fiore’s findings correspond reasonably well with those of a five-month survey of 618 British households, in which 986 cats brought home 14,370 prey items. This research revealed that, although 91% of cats returned at least one item, “approximately 20–30% of cats brought home either no birds or no mammals.” [5] Her results also seem to be in line with those published by Churcher and Lawton, whose yearlong “English Village” study (involving approximately 70 cats and 1,090 documented prey items) found that that 8.6% of cats brought home no prey [4] (though the authors don’t specify the percentage of cats that returned no birds).

On the other hand, it is not uncommon for such studies to find that more than half of the study cats returned no prey. In their pilot study of cat predation in Bristol (UK), for example, Baker et al. reported that 77 cats returned a total of 212 prey items to 52 participating households, but that “in each sampling period, the majority of cats (51–74%) failed to return any prey.” [6] Their subsequent 12-month study (this time involving 186 Bristol households, 275 cats, and 495 prey items) found a similar level of apparent non-hunters: roughly 61%. [7]

Any number of factors might contribute to these apparent differences, perhaps the most likely “culprits” being environmental (e.g., density of both birds and cats, habitat type and size, etc.) and sampling bias (as Baker et al. put it, “cat owners whose pets were killing lots of birds may have wished to hide the fact; alternatively, they may have been keen to show off their cat’s prowess.” [7])

Add It Up

Fiore began to quantify predation by calculating, based on the number of birds brought home by study cats, an average number of birds killed each year per cat. But, as I’ve discussed previously, using the average to describe predation rates (the distribution of which is highly skewed) overestimates the impact of cats on wildlife. Barratt offers a useful rule-of-thumb method (one echoed by Fitzgerald and Turner [8]) as an alternative:

“…median numbers of prey estimated or observed to be caught per year are approximately half the mean values, and are a better representation of the average predation by house cats based on these data.” [9]

Using the median—1.91 birds/cat/year—instead of the mean, cuts Fiore’s estimated predation rate of 3.44 nearly in half. (Among the more puzzling items I uncovered while reviewing Fiore’s thesis was her apparent miscalculation of the average predation rate—where Fiore comes up with 3.44 birds/cat/year, I get only 2.79. See Note 3 for a detailed explanation.)

In any case, what’s far more interesting is how Fiore adjusts her estimate based on the results of feathers discovered in scat.

Scat Analysis

Three of Fiore’s participants (who, together, owned six of the study cats) collected and bagged their cats’ scat for five consecutive days on a monthly basis. A fourth owner participated in this part of the study for just one month, and collected scat for three days.

Additional scat data was acquired via “litter box cleanups,” in which “a few volunteers were convinced to bag the entire contents of the litter box when it was cleaned.” [3] The results, according to Fiore, were rather dramatic:

“Out of 215 separate scat analyses, each of which could have composed several beakers of fecal material, feathers were found a total of 28 times. In only one instance, however, did the owner know that a bird had been killed and/or consumed.” [10]

Equally dramatic were the mathematical and statistical gymnastics Fiore employed to arrive at her conclusions. Her figure of 21%, for example, as “a mean value of the percentage of time a cat could be expected to ingest a bird with no owner knowledge,” [10] remains a mystery to me. Despite numerous attempts, I have been unable to sort out exactly how Fiore arrived at this figure.

Dividing 27 occurrences of “unexpected” feathers by 214 total analyses (subtracting in each case for the one instance of “expected” feathers) ought to get us close, it seems—but falls well short (12.6%).

Litter Box Cleanups

Of the 215 analyses, 24 were litter box cleanups, a data collection method plagued with problems. To begin with, only 11 owners (representing 19 cats) participated. Fiore acknowledges the limitations associated with this small sample size, but overlooks a thornier issue.

Fiore considered each cleanup—regardless of how many cats were using the litter box, or for how many days—a single data sample. If a feather was found during analysis (the details of which are described on Fiore’s website), then one additional kill was attributed to a single cat (again, alternating among cats in multi-cat households). While this is a conservative approach in one respect—no more than one bird could be recorded for any positive result—it fails to adequately account for the high number of negative results. A litter box containing the waste of three cats, accumulated over a period of five or more days (six of the 24 cleanups were of this type, and in only one case were feathers found), was treated no differently from one containing a single day’s waste from one cat.

This per-household approach allows a negative result in the first case to be offset by a positive result in the second—despite their very different implications.

On the other hand, at least two volunteers involved in the litter box cleanups also owned indoor cats, and it was impossible to determine whether it was their indoor or indoor/outdoor cats that were “contributing” to the study. This may have resulted in some false negatives.

Given all the uncertainty involved with Fiore’s litter box cleanups, it’s difficult to see how this aspect of her study contributes in any meaningful way to the overall findings. Better, I would say, not to include these results in any calculations—and perhaps disregard them entirely.

Monthly Collections

Fiore’s primary method (making up 191 of the 215 analyses) for scat analysis proved less problematic than the litter box cleanups—but was not without its own shortcomings.

Again, the sample size was quite small—only four participants in all (representing seven cats). And, once again, owners of multiple cats (two of the three long-term participants) were treated—from a statistical point of view—as if they each owned just one cat. A negative result in a three-cat household was weighted the same as an instance of feathers found in a single-cat household.

Worse, by alternating attributions of kills that could not linked to a specific cat in a multi-cat household, Fiore effectively makes hunters out of non-hunters (see Note 2 for a detailed explanation). In fact, given enough of these attributions—and it wouldn’t take many—all of the study cats would be categorized as killers.

Taking into account the number of cats in each household that participated in monthly collections (see Note 4), the number of scat analyses rises dramatically, from 215 to 354—and the average occurrence of feathers drops to just 7.6%.

Lucky 13

In the case of Cat 13—the study cat with the most “scat kills” (instances of feathers detected in scat when no birds were returned home) by far—feathers were found in 14 of 80 (17.5%) daily samples collected, prompting this reaction from Fiore:

“It is interesting to speculate as to the outcome of this study if all the volunteer owners had been as conscientious as this particular owner in collecting scat every month. Additionally this owner, who is retired, is very mindful of her cat’s whereabouts but still failed to find many kills.” [3]

But even Cat 13’s apparent penchant for secretive hunting yielded a frequency of found feathers well below Fiore’s suggested overall rate of 21%. And what about the other two long-term participants, whose 23 monthly samples (108 days’ worth—collected from five cats, not one, don’t forget) revealed just eight occurrences of feathers? Their frequency of secretive hunting was 7.4%—before accounting for the multiple cats involved (as described in Note 4), which would drop the rate to just 3%.

Was the owner of Cat 13 any more conscientious than the other two? Perhaps. Fiore notes that this woman, “appeared to be very serious about the study and never failed to turn in scat on a monthly basis; reminders were never required.” [3] Still, the other owners were hardly sitting on the sidelines—they turned in 108 samples between them. And it’s not clear what detrimental effect requiring a reminder might have had on the results; on the contrary, Fiore writes: “It is believed that scat volunteers conducted their collection correctly.” [3]

It’s difficult not to detect bias in Fiore’s praise for the diligence demonstrated by Cat 13’s owner—or, more to the point, her appreciation for the cat’s performance. Although this cat’s behavior is—as illustrated by Fiore’s own data—exceptional, Fiore seems to suggest that it’s the norm.

Corroboration and Disclaimers

Fiore is quick to point out various factors that would have allowed kills to go undetected by scat analysis. The condition of the birds recovered, for example, suggests that some cats don’t eat their prey, in which case scat would not have contained feathers. Nestlings, because they lack feathers, also would go undetected.

And even adult birds, suggests Fiore, may not have feathers to be discovered later. “Generally,” she writes, “cats pluck the feathers before consuming the bird.” [3] Although Fiore cites the work of other researchers on this point (work I’ve yet to chase down), her own findings seem to contradict this claim; plenty of feathers were found in scat. (Fiore’s claim also begs the question: If cats are expected to strip the feathers from the birds they kill, why use feathers found in scat as a measure of predation?)

Fiore is doubtful that “one of the study cats ate a bird it did not kill and that in turn feathers were detected in the scat,” [3] but Fitzgerald and Turner have suggested otherwise:

“Carrion is eaten, but is difficult to distinguish from animals killed by cats, unless it is from a large animal that a cat could not kill (e.g., sheep or kangaroo). Even the presence of maggots with the food is not a certain indicator, because cats may return later to prey they have killed and cached.” [8]

Although Fiore acknowledges the challenges inherent in her analysis method, she argues that they are outweighed by the benefits:

“Scat analysis is probably the most reliable estimate of bird kills, although it is a very conservative one. The results are hard to refute. When a feather is found it is proof that a kill was made or a carcass consumed… scat analysis is important because often cats do not bring their kills to the owner, and frequently the owner is not home to accept a kill should one be presented. Many of the owner volunteers reported not seeing their cat(s) for many days in a row (one owner did not see her cat for several months during the study). Collected kills were very conservative, and seemed to be based in part on the relationship of the owner with their cat(s). Unfortunately, absentee owners were the ones most unwilling to provide scat.” [3]

It seems Fiore wants to have it both ways: When it comes to defending the value of scat analysis, she’s quick to point out how much predatory activity the owners might be missing. When she’s emphasizing the conservative nature of prey tallies, though, Fiore cites a number of detailed firsthand accounts from cat owners—painting a rather different picture of owner involvement:

- “There were numerous calls during the course of data collection about missing remains, cats seen eating birds but no remains could be found, cat running off with prey…”

- “The wife of one of the volunteers admitted to seeing her cat drag a cardinal under the porch, but she would not retrieve it…”

- “The owner of Cat 30 reported that she had seen… her cat eat an entire bird (even the head) and that there was no evidence left to give us.”

Her inconsistency raises questions not only about her findings, but also—far more unsettling ones—about her objectivity as a researcher.

Found Feathers

Despite results that are—at best—mixed, Fiore’s conclusions are imbued with certainty and drama. They also tend to misrepresent her research. Fiore’s claim that “scat analysis may indicate, as in this study, that a far greater number of birds are consumed than was previously thought” [3] is based on her misuse of means to characterize predation levels. Using medians instead, it becomes clear that—in terms of the distributions’ central tendency—there is no difference between her original data set and the one that includes scat kills.

More problematic, though, are Fiore’s claims about the secretive hunting habits of cats:

“Probably the most important information which can be gained from the scat analysis (coupled with owner bird collection) is that most cats do kill birds. And in all cases but one, when feathers were found in scat, the owner was unaware that the cat had eaten a bird. This and other data from this study would seem to refute Dr. Patronek’s claim that ‘cats tend to bring prey home.’” [3] (See Note 5 for details regarding Fiore’s apparent dispute with Patronek.)

Actually, Fiore’s own data indicate that cats do, in fact, “tend to bring prey home”—nearly four in five, if her mysterious 21% figure is to be believed. And her assertion about the surprising nature of kills revealed through scat analysis is—although technically true—highly misleading. She seems to be suggesting that scat collection was done randomly, in which case we would expect some collections to correspond with documented kills. Fiore’s reporting, however, indicates no such randomness. In fact, it’s entirely likely that participants (thinking such activity would at least be redundant, or worse, detrimental to the study) would have collected scat only when they were unaware of their cat(s) having killed a bird.

By framing her findings this way, Fiore effectively dismisses the vast majority of analyses (187 of 215, or 87%, using her analysis method; 326 of 354, or 92%, accounting for multi-cat households) in which no feathers were found.

When the ABC summarizes Fiore’s work in their brochure Domestic Cat Predation on Birds and Other Wildlife, they only make matters worse by conflating different aspects of her research:

“In a study of cat predation in an urban area, 83% of the 41 study cats killed birds. In all but one case, when feathers were found in scat, the owner was unaware that their cat had ingested a bird. In fact, the majority of cat owners reported their cats did not bring prey to them. Instead, the owners observed the cats with the bird or found remains in the house or in other locations.” [11]

Reading the ABC’s version, one might easily get the impression that all 41 cats were involved in the scat analysis, or that the scat collections were done randomly. (Or that cats, in order to be considered cooperative participants in predation studies, are expected to deposit their prey in the laps of their owners, or some other pre-determined location.)

Connecting the Dots

Let’s set aside my (numerous) complaints regarding Fiore’s scat analysis, and my claim that she both miscalculated and misused the average predation rate. Assuming both figures are valid, Fiore’s use of that 21% figure to adjust the predation rate upward, from 3.44 to 4.2 birds/cat/year is also a problem. The scat analysis should (again, assuming it was done properly, included sufficient sample sizes, etc.) reveal something about the secretive hunting behavior of the study cats—in terms of (1) its frequency, and (2) its extent. Fiore’s misstep is in linking the frequency directly to predation levels.

Properly adjusting the estimated predation level would involve, first, correcting the proportion of cats that hunt to account for the frequency of secretive hunters. Using Fiore’s data to illustrate:

71% + [(100%-71%) x 21%] = 77%

Once we adjust for those cats that don’t bring prey home, we can multiply this figure by the number of outdoor cats (see Note 6). Again, using Fiore’s data (described in the Cat Density section below):

40,836 pet cats x 43% allowed outdoors = 17,559 hunting cats

Multiplying this result by the median predation rate (1.91), we get a total of 33,538 birds/year killed by pet cats in Wichita—less than half Fiore’s estimate of 73,750. (This figure might be refined further by considering separate predation levels: one for the secretive hunters, and another for those cats known to bring prey home. Unfortunately, Fiore’s sample size is too small to make such a comparison, but it’s not difficult to imagine different hunting behaviors resulting in different success rates.)

To reiterate, I’m using Fiore’s numbers here only to illustrate how I would connect the dots between scat analysis results and predation levels.

Two Key Points

Fiore’s goal of obtaining a more accurate tally of birds killed by cats was (and is) admirable. However, her use of scat analysis was largely unsuccessful in achieving that goal. In fact, Fiore’s analysis method actually added to the uncertainty in two important ways:

- By alternating attributions of kills that can’t be linked to any one cat in a multi-cat household, Fiore essentially categorizes each one of them as a hunter.

- By weighting multi-cat households no differently from single-cat households, Fiore ignores a great deal of evidence suggesting that most cats are not, in fact, hunting without their owners’ knowledge. Although the number of “scat kills” is conservative as a result, her analysis method gives greater importance to what is unknown than to what is known.

Radio Tracking

Among the many challenges Fiore ran into while trying to track study cats were owner objections, physical barriers (e.g., fences), and radio signal strength/continuity in an urban setting. As a result, she was able to study only eight cats for a total of 57 hours (almost all during daylight hours).

Given the limited value of Fiore’s tracking activities—and my focus on the aspects of her thesis that pertain more directly to predation—I’ll move on to her estimate for the number of cats in Wichita.

Cat Density

Fiore used two different methods to estimate the number of cats in Wichita. The first, which is rather clever, involved combining the results of two telephone surveys: the Pet Ownership Survey was used to (among other things) poll respondents about whether or not they had vaccinated their cat(s) against rabies; a survey of local veterinarians was used to estimate the annual total of such vaccinations in Wichita. “If 500 cats received vaccinations,” writes Fiore, “and respondents indicated that 50% of pet cats had been vaccinated, 1000 cats would be the expected density.” [10]

For the second method, Fiore multiplied the number of Wichita households by the estimated number of cats per household (1.52), as determined through a random telephone survey.

Results of the first method yielded an estimate of 35,737 pet cats in Wichita, whereas the second method produced an estimate of 40,836 pet cats. (The skewed nature of the cats/household distribution (many owners having one or two cats, and a few having many cats) will tend to push such estimates upward.)

In addition, Fiore estimates (in her original thesis document, but not in the summarized version that appears on her website) the number of stray and feral cats in the city, ultimately arriving at a figure of 124,537. Deriving such estimates is always dodgy work, as so little trustworthy information is available. Additional caution is in order when these figures are used to project predation levels of stray and feral cats, as Fiore has done (as described in the Christmas Bird Count section, below).

For one thing, there are some questionable assumptions wrapped up in her estimates—not the least of which is that the predation rates and patterns of stray and feral cats are similar to those of pet cats. Clifton has suggested that they are not:

“The feral cat toll on birds is unlikely to be more than half as high as the pet cat toll. First, there may be twice as many free-roaming pet cats as ferals old enough to hunt for a living. Second, ferals who hunt for a living tend to hunt mice by night, not birds, who are mostly not out at night. Third, feral cats appear to hunt no more, and perhaps less, than free-roaming pet cats. This is because, like other wild predators, they hunt not for sport but for food, and hunting more prey than they can eat is a pointless waste of energy… Finally, relatively few cats are even capable of successfully hunting birds.” [2]

Christmas Bird Count

Fiore used data from the Wichita Audubon Society’s “first area-wide bird count of Northern Cardinals,” [3] an event coinciding with the National Audubon Society’s 99th annual Christmas Bird Count. Combining this data with the number of households in the city, she estimated that there were 316,477–424,922 cardinals in Wichita at the time.

It’s important to remember, as is made clear on the North American Breeding Bird Survey website, that such surveys provide “an index of relative abundance, rather than a complete count of breeding bird populations.” Fiore admits, “a census of a single bird species effected [sic] by urban cats in Wichita is an estimate of population density within an accuracy of one order of magnitude,” [3] but persisted.

As a result, Fiore was able to compare estimates of the overall cardinal population with estimates of those killed by cats. However, her “accounting practices” suggest that she’s not exactly impartial on the subject of predation. Fiore states unequivocally, for example, “the mean of 2.98… cardinals seen per residence is high as very few surveys were returned by people who saw no cardinals.” [3] Sure that “people only reported when they saw cardinals, thus skewing the data towards high values,” Fiore discards the mean and uses frequency quantiles instead.

Among the possible sources of participant bias Fiore cites:

“…adding counts together rather than reporting total numbers seen at one time, counting birds on someone else’s property, estimating numbers by song alone, or sending in the forms with numbers that did not exist on December 19 but that the resident had seen on some previous occasion.” [3]

Perhaps she was correct in her assessment, but it’s peculiar that Fiore never expressed a similar concern for her obviously skewed distribution of birds killed by cats—and as a result, overestimated predation levels. In short, she seems determined to lower the estimate of birds in the area while at the same time raising the estimate of birds thought to be killed by Wichita’s cats. (In fact, her thesis is littered with such maneuvering; Fiore uses nearly every instance of uncertainty to imply an impact on wildlife greater than her research actually suggests.)

Fiore’s bird collection data indicated that 7% of the birds taken were Northern Cardinals. Combining this figure with her estimates of the populations of all outdoor cats and cardinals in Wichita, she concludes, “there are at least 43,035–50,285 Northern Cardinal deaths per year due to cat predation.” [3] This corresponds to roughly 15% of her estimated cardinal population—a figure Fiore describes as “extremely conservative.”

Impact of Free-roaming Cats

Considering the numerous limitations of her study (many of which she acknowledges), Fiore seems quite comfortable extrapolating her results—arguing, for example, that “over half a million birds meet their death each year in the city of Wichita because of a cat.” [3] Of course, this figure relies on dubious estimates of the number of outdoor cats, an exaggerated predation estimate, and other factors that cast serious doubt on its accuracy.

Fiore’s confidence may come, in part, from the fact that other researchers have reported similar findings. But, as I have gone to great lengths to emphasize over the past few months, such findings rarely hold up to careful scrutiny. And sometimes, results are simply misunderstood—as when Fiore misinterprets Fitzgerald’s work:

“…several studies have been done to access [sic] the importance of birds as a percentage of total diet, as in Fitzgerald [12] who estimates birds represented 21% of cat diets.” [3]

In fact, Fitzgerald was referring not to the percentage of dietary intake, but of how often birds were found in scat or stomach contents (a distinction I explain in detail here):

“On all continents, birds are usually much less important than mammals; birds were present on average at 21 per cent frequency of occurrence, and mammals at 68 per cent. Many species are represented by just one or two individuals.” [12]

Something else Fiore overlooks is that the type of predation observed by her participants may have been largely compensatory; that is, the birds killed were of sufficiently poor health that they were unlikely to survive anyhow. Two studies have reported such findings. [7, 13] If this were the case, even her inflated estimates—however dramatic sounding—would actually have little impact on the population of Wichita’s birds.

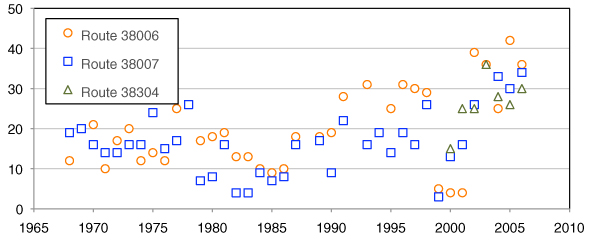

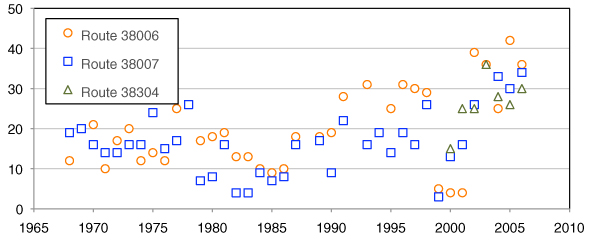

In any case, the cardinals in the area seem to be doing fine. Between 1970 and 2000, Wichita’s human population increased 24.5%, from 276,554 to 344,284. Such an increase—accompanied by various related development activities—is generally associated with habitat loss, fragmentation, pollution, and any number of other factors that adversely affect bird populations. Including more cats. Nevertheless, data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey suggests that the number of Northern Cardinals in the area was on the increase over this period.

Caption: BBS Data: Northern Cardinals for Three Wichita-area Survey Routes (adapted from North American Breeding Bird Survey website)

Cat Regulations

Fiore used a telephone survey of Wichita residents to inquire about a range of pet ownership issues, as well attitudes concerning possible regulations affecting cats/cat owners. Among the questions Fiore posed to Wichita pet owners:

“At the present time dogs have to be licensed and kept on leashes. How do you feel about having cats regulated so that they would have to be licensed and confined to the owner’s property?”

Thirty-one percent of cat owners were completely opposed, while 44% said they were at least somewhat in favor—“a surprisingly high figure,” as Fiore notes. Pet owners were then asked a follow-up question:

“If it were found that unregulated cats are killing too much wildlife, would you change your opinion?”

Survey results are always tricky to interpret, and two people can often draw very different conclusions from them. Rather than focus on the responses, then, I’d like to take just a moment to focus on the question—starting with the term unregulated. Is that even necessary? How about simply cats? And what do me mean by wildlife here? And how much is too much?

Nearly half of respondents said that they would not change their minds, and Fiore sounds downright exasperated with their explanations:

“Cat owners are in denial about what their cats are doing. They seem sad over the death of a cardinal, but they refuse to take responsibility for the cat by stating ‘There is nothing I can do’ or ‘…but that’s what cats do.’ The owner of study cat 14 wrote ‘Cats are part of nature same as birds. Species come and go. I don’t think nature should be artificially regulated.’” [3]

Fiore clearly disagrees. Indeed, she tipped her hand much earlier, when, in Chapter 1, she wrote:

“If a human killed any of these birds or was caught in possession of them without a valid permit, he or she would face penalties including fines, and depending on the severity and species, possible jail time. Cats across America and their owners face no punishment.”

* * *

A story in the April 18, 1998 edition of The Wichita Eagle explained Fiore’s proposed project this way:

“Fiore, a graduate student at Wichita State University, will spend a year counting Wichita cats and their feathered victims for her master’s thesis. As bird populations decline, Fiore thinks it’s important to know how far cats are sinking their teeth into the feathered world… She points out that even the cutest kitty can be a remarkable hunter, although skill varies from cat to cat. But Fiore doesn’t want people to think she’s anti-cat. ‘I’m out to study the problem.’” [14]

In the same piece, Fiore brings up the Wisconsin Study (referring to its “intermediate value” of 39 million birds), and it’s revealed that she’s the vice president of the Wichita Audubon Society. Nevertheless, Fiore assures readers of her objectivity: “We’re just scientists who want to see if there’s a problem.”

Fiore’s thesis dedication, too, suggests an air of integrity and goodwill:

“This thesis is dedicated to my cat owner volunteers who made this study possible and to cat lovers and bird lovers around the world in the hopes that we can all work together to preserve native wildlife.” [3]

Having spent weeks reviewing Fiore’s work, though, I’m not buying it. In fact, I can’t help but read in her dedication an inside joke of sorts: her invitation is to preserve native wildlife; domestic cats, as she makes clear elsewhere, are not native.

In a follow-up story for The Wichita Eagle, Fiore reported her results: Wichita cats kill anywhere from 542,000 to 645,000 each year. But, according to the Eagle’s Roy Wenzl, it wasn’t the results that got some residents worked up. “Fiore’s study upset people. Not what she found. But what she did, in raising the question.” [15]

“‘I didn’t understand that,’ said Bob Gress, a cat owner, a naturalist and the director of the Great Plains Nature Center, who helped her with her study. ‘All she was doing was collecting information. I don’t think any of us should ever be afraid of the truth,’ Gress said. ‘But some people saw this as an assault on cats. Even some veterinarians seemed to resent what she was doing.’” [15]

Gress’ comment got me thinking not just about Fiore’s thesis, but also about how it’s been used—primarily by the ABC. As much as we might like to believe otherwise, scientific inquiry doesn’t happen in a vacuum; there is always a context to consider. It’s clear from her document that Fiore was well aware of the debate surrounding free-roaming cats at the time—and must have a good idea, too, of the possible implications of her work (e.g., ammunition for those who oppose free-roaming cats and TNR, the possible wholesale extermination of stray and feral cats, etc.).

And then there’s the matter of just how much truth there is in Fiore’s findings—plagued as they are by her flawed analysis and obvious bias.

Which is not to say that she (or anybody else) should be discouraged from studying such complex, controversial issues. But there is a great responsibility that comes with such endeavors. Fiore, in her thesis work, simply didn’t live up to that responsibility.

Notes

1. Fiore writes: “A researcher in southern Illinois estimated that his three house cats, which he followed for 6 years, only brought home about 50% of killed prey.” [16] As I’ve pointed out previously, this is a surprisingly common misunderstanding of George’s work. In fact, George was merely adjusting predation levels based on the fact that the “delivery area” was not always monitored: “…the study registered 50 percent of the cats’ captures—a percentage roughly corresponding to: 1, the average amount of total time the delivery area was under observation for recording prey; and 2, the number of prey items logged in the same year when the delivery area was under continuous day-and-night scrutiny, compared to the number logged (during equivalent seasonal and hourly periods) when continuously scrutinized for lesser amounts of time.” [16]

2. Fiore provides little detail regarding the application of her alternating attribution method, requiring some speculation on my part. An example, however, may prove illustrative. Consider Cats 17 and 18, which lived in the same home. During the bird collection phase of the study, Cat 17 was credited with just two kills. Cat 18, on the other hand, brought home 17 birds—clearly the more successful hunter. The question is: Did Cat 17 really kill those two birds, or are these simply the result of kills that could not be attributed to either cat?

At any time during the yearlong study, kills that could not be connected directly to a particular cat were, as Fiore explains, “alternated between cats.” Imagine if, at the time Cat 17 had 15 known kills, another kill was discovered—but this time, it was unclear which cat was responsible. That kill, then, would be attributed to Cat 17, bringing its total to 16. The next such kill would be attributed to Cat 18—effectively shifting its status from non-hunter to hunter. Two more such instances would yield the results described by Fiore: two kills for Cat 17 and 17 for Cat 18—though it should be clear that just two “mystery kills” would, using Fiore’s analysis method, create the impression that both cats are hunters. (In fact, were it not for their random numbering—Cat 17 being credited with the first “mystery kill” only because of its lower ID number—such an impression would result from just one such kill.)

To be clear: the scenario described above is speculative. But, given the impact of Fiore’s alternating attributions—increasing rather dramatically the proportion of apparent hunters—careful scrutiny is warranted.

3. Calculating the mean should be quite straightforward, of course. Fiore first calculated a daily rate for each cat by dividing that cat’s catch by the number of days in which its owner participated in the study. She then averages that rate over all 41 cats (coming up with 0.0094, compare to my 0.0076), and multiplies the result by 365 days/year.

4. Using this analysis method, a five-day collection from a three-cat household would constitute not five, but 15 analyses. Now, there’s no way of knowing that all three cats contributed to the scat collection; conversely, there’s no reason to think that just one cat contributed, as Fiore assumes.

5. At times, Fiore’s thesis reads as if it was a rebuttal to Gary Patronek’s article, Free-roaming and feral cats—their impact on wildlife and human beings, which was published around the time Fiore was conducting her research. Interestingly, had Fiore read Patronek’s paper more closely, she might not have used the mean to estimate predation rates. “The small proportion of cats with a large number of kills,” writes Patronek, “indicate that the number of animals killed per cat has a skewed distribution, which would tend to bias the mean upward.” [17]

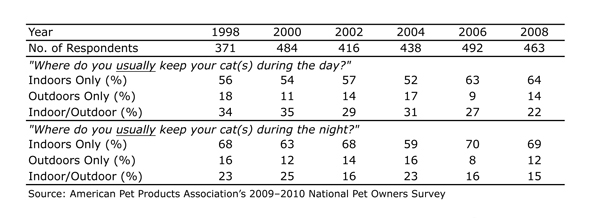

6. Fiore is skeptical of her Pet Ownership Survey results, which indicate that 43% of cat owners keep their cats indoors (“People who interpreted this question to mean that because the cat was inside ‘most of the time’ it was an indoor cat, would be incorrect for purposes of this study.” [10]). However, as Merritt Clifton points out, it’s likely that she actually overestimates the number of outdoor cats when she “decided, based on a survey of Wichita residents, that about half of all cat-keepers allow their cats to roam, and presumed that could be extrapolated to mean that half of all pet cats roam.” This, writes Clifton, contradicts Animal People findings “that cat-keepers whose cats do not roam have, on average, from two to three times more cats than those whose cats can roam.” [2] Further support comes from a 2003 survey that found 60% of cats were kept strictly indoors, and nearly half of those allowed outdoors were out for less than two hours each day. [18]

Literature Cited

1. Dauphiné, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2009. p. 205–219.

2. Clifton, M. Where cats belong—and where they don’t. Animal People 2003 [cited 2009 December 24]. http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/03/6/wherecatsBelong6.03.html.

3. Fiore, C.A., The Ecological Implications of Urban Domestic Cat (Felis catus) Predation on Birds In the City of Wichita, Kansas, in College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. 2000, Wichita State University: Wichita, Kansas

4. Churcher, P.B. and Lawton, J.H., “Predation by domestic cats in an English village.” Journal of Zoology. 1987. 212(3): p. 439-455.

5. Woods, M., McDonald, R.A., and Harris, S., “Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain.” Mammal Review. 2003. 33(2): p. 174-188.

6. Baker, P.J., et al., “Impact of predation by domestic cats Felis catus in an urban area.” Mammal Review. 2005. 35(3/4): p. 302-312.

7. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86-99.

8. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

9. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by house cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. II. Factors affecting the amount of prey caught and estimates of the impact on wildlife.” Wildlife Research. 1998. 25(5): p. 475–487.

10. Fiore, C.A. and Sullivan, K.B. (2000) Domestic Cats (Felis catus) Predation of Birds in an Urban Environment. http://www.carolfiore.com/Article.html Accessed July 27, 2010.

11. ABC, Domestic Cat Predation on Birds and Other Wildlife. n.d., American Bird Conservancy: The Plains, VA. www.abcbirds.org/abcprograms/policy/cats/materials/predation.pdf

12. Fitzgerald, B.M., Diet of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 1988, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York. p. 123–147.

13. Møller, A.P. and Erritzøe, J., “Predation against birds with low immunocompetence.” Oecologia. 2000. 122(4): p. 500-504.

14. Potter, T., Counting Cats and Their Winged Prey, in Wichita Eagle, The (KS). 1998. p. 9A

15. Wenzl, R., Are You Harboring a Killer on Your Couch?, in Wichita Eagle, The (KS). 1999. p. 9A

16. George, W., “Domestic cats as predators and factors in winter shortages of raptor prey.” The Wilson Bulletin. 1974. 86(4): p. 384–396.

17. Patronek, G.J., “Free-roaming and feral cats—their impact on wildlife and human beings.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1998. 212(2): p. 218–226.

18. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545.

![]()