“The cat, of all animals, is in some respects the most intimate companion of man… Nevertheless, it leads a dual existence. ‘The fireside sphinx,’ the pet of the children, the admired habitué of the drawing-room or the salon by day, may become at night a wild animal, pursuing, striking down and torturing its prey, frequently making night hideous with its cries, sneaking into dark, filthy, noisome retreats, or taking to the woods and fields, where it perpetrates untold mischief. Now it ravages the dovecote; now it steals on the mother bird asleep on her nest, striking bird, nest and young to the ground. In the darkness of night it turns poacher. No animal that it can reach and master is safe from its ravenous clutches.” —Edward Howe Forbush, The Domestic Cat: Bird Killer, Mouser and Destroyer of Wild Life; Means of Utilizing and Controlling It (1916)

Among the numerous criticisms of “Feral Cats and Their Management,” we can now add lack of originality.

In the January/February issue of Animal People, editor Merritt Clifton confirms his “hunch that ‘Feral Cats and Their Management’ is little more than a paraphrased and condensed update of the 1916 tract The Domestic Cat: Bird Killer, Mouser and Destroyer of Wild Life; Means of Utilizing and Controlling It, authored by then-Massachusetts state ornithologist Edward Howe Forbush.”

After a careful re-reading of the 1916 work (available online), Clifton (whose comprehensive article, “Where Cats Belong—and Where They Don’t,” I have quoted repeatedly) concludes:

“…the University of Nebraska paper and the Forbush work follow almost identical outlines from beginning to end, making similar allegations, arriving at the same recommendations in closely parallel language.” [1]

“The major structural difference,” writes Clifton, has to do with the sources involved. Whereas Forbush relied largely on “anecdotal testimony from more than 200 individual correspondents” (much of it from hunters who were after the same birds the cats were pursuing), Hildreth, Vantassel, and Hygnstrom provide “no firsthand testimony.” [1]

Instead, notes Clifton, they “plugged in references to more recent studies… in support of essentially the same claims, including that cats devastate populations of birds who would otherwise be hunted.” [1]

Among the similarities described in Clifton’s article:

Fecundity

Like Forbush, the authors of “Feral Cats and Their Management” use “outlandishly high claims about feline fecundity” [1] to drum up support for their eradication (“Hence the necessity for checking such increase promptly by killing all superfluous kittens soon after birth,” [2, p. 19] as Forbush put it).

For their reprise of Bird Killer, Mouser and Destroyer of Wild Life, Hildreth, Vantassel, and Hygnstrom turn to a frequently cited—but bogus—figure:

“The Humane Society of the United States estimates that a pair of breeding cats and their offspring can produce over 400,000 cats in seven years under ideal conditions, assuming none die.” [3]

But of course, feral cats—like all animals, and especially those living outdoors—don’t live “under ideal conditions.” And kittens do die. (The fact that Hildreth, Vantassel, and Hygnstrom leave it that is telling: their intent has nothing whatsoever to do with science, or research of any kind.)

In fact, the Wall Street Journal’s “Numbers Guy,” Carl Bialik, discredited this myth four years earlier in his column. What’s more, John Snyder, Vice President, Companion Animals, told Bialik then that HSUS wasn’t the source, adding, “that number is flawed.” (I’ve searched the HSUS website and can find no mention of it.)

Predation and Impact

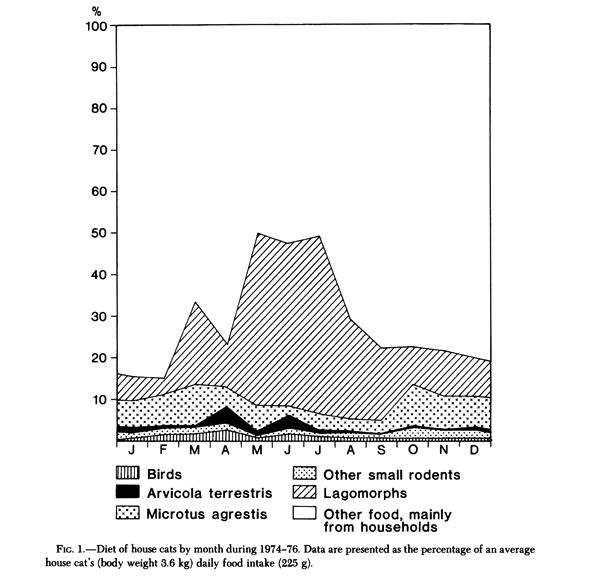

Clifton points out that Forbush ignored reliable information indicating that free-roaming cats kill, on average 10 or 11 birds annually, and instead “dwelt on the claims of 15 people that their cats killed 20.4 birds per month, and the claims of six people that their cats killed about 50 birds per year.”

It’s not clear what information Hildreth, Vantassel, and Hygnstrom relied on, as they didn’t bother with in-text citations. Whatever the source, the authors settled on a surprisingly conservative annual predation rate of eight birds per year, and used 60 million as the estimated number of feral cats in the U.S. This, too, might be considered conservative in light of other “estimates,” (the American Bird Conservancy, for example, claims—without citing any source—that the population is 120 million) though Clifton himself estimated, in 2003, that “the winter feral cat population may now be as low as 13 million and the summer peak is probably no more than 24 million.” [4]

Rather than relying on inflated predation rates to justify the eradication of feral cats, Hildreth, Vantassel, and Hygnstrom misrepresent well-known scientific studies of their impact on wildlife. Their “interpretation” of Olof Liberg’s 1984 paper, for example, and convenient omission of sample size (26 rodents, 21 birds, and 11 lizards) in their reference to Crooks and Soulé’s 1999 paper. [5]

And, not surprisingly, “Feral Cats and Their Management” makes no mention of compensatory predation.

Public Health Threats

“As a carrier of disease,” argued Forbush, “especially to children, no animal has greater opportunities [than the domestic cat].”

Among the threats suggested by Hildreth, Vantassel, and Hygnstrom are cat scratch fever, plague, rabies, ringworm, salmonellosis, fleas, and ticks. And toxoplasmosis—of particular concern, apparently, because “in 3 separate studies, most feral cats (62 percent to 80 percent) tested positive for toxoplasmosis.” [3]

But the rate of cats testing positive—or seroprevalence—is not a useful measure of their ability to infect other animals or people. Indeed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

“Although cats can carry diseases and pass them to people, you are not likely to get sick from touching or owning a cat… People are probably more likely to get toxoplasmosis from gardening or eating raw meat than from having a pet cat.”

• • •

“Much of Forbush’s antipathy toward cats,” suggests Clifton, “might be ascribed to the context of the times.”

“His life coincided with the era in which New England wildlife was more depleted than at any time since. Logging, ploughing, damming, and unrestrained development depleted the forest cover, the grasslands, and the rivers. Precocious as Forbush was in his birding, which then was done chiefly with a shotgun, predatory mammals, fur-bearers, and most wild species considered edible had already been extirpated from most of Massachusetts before he had much chance to see or kill them.” [1]

That was 1916. How to explain “Feral Cats and Their Management,” written 94 years later—in, presumably, a very different context? The answer—part of it, anyhow—may lie with one of the paper’s co-authors, Stephen Vantassel, whose PhD dissertation was dedicated to:

“…fur trappers who, every winter, brave the harsh weather in continuance of America’s oldest industry. Regrettably, they must also endure the ravages of urban sprawl and the derision of an ungrateful and ignorant public.” [6]

Vantassel, it seems, would be more at home in the early twentieth century than in the twenty-first. (Though, by 1916, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was already 50 years old, and the burgeoning animal welfare/right movement would surely have Vantassel longing for “the good old days.”)

Literature Cited

1. Clifton, M. (2011, January/February). The Domestic Cat: Bird Killer, Mouser and Destroyer of Wild Life; Means of Utilizing and Controlling It, by Edward Howe Forbush. Animal People, p. 17, from http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/11/1/Jan-Feb2011.zip%20Folder/Ho8j3PWe.html

http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/11/1/Jan-Feb2011.pdf

2. Forbush, E.H., The Domestic Cat: Bird Killer, Mouser and Destroyer of Wild Life; Means of Utilizing and Controlling It 1916, Boston: Wright and Potter Printing Company.

3. Hildreth, A.M., Vantassel, S.M., and Hygnstrom, S.E., Feral Cats and Their Managment. 2010, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension: Lincoln, NE. http://elkhorn.unl.edu/epublic/live/ec1781/build/ec1781.pdf

4. Clifton, M. Where cats belong—and where they don’t. Animal People, 2003. http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/03/6/wherecatsBelong6.03.html.

5. Crooks, K.R. and Soulé, M.E., “Mesopredator release and avifaunal extinctions in a fragmented system.” Nature. 1999. 400(6744): p. 563–566. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v400/n6744/abs/400563a0.html

6. Vantassel, S.M., Dominion over Wildlife?: An Environmental Theology of Human-Wildlife Relations. 2009: Resource Publications.