In April, Conservation Biology published a comment authored by Christopher A. Lepczyk, Nico Dauphiné, David M. Bird, Sheila Conant, Robert J. Cooper, David C. Duffy, Pamela Jo Hatley, Peter P. Marra, Elizabeth Stone, and Stanley A. Temple. In it, the authors “applaud the recent essay by Longcore et al. (2009) in raising the awareness about trap-neuter-return (TNR) to the conservation community,” [1] and puzzle at the lack of TNR opposition among the larger scientific community:

“…it may be that conservation biologists and wildlife ecologists believe the issue of feral cats has already been studied enough and that the work speaks for itself, suggesting that no further research is needed.”

In fact, “the work”—taken as a whole—is neither as rigorous nor as conclusive as Lepczyk et al. suggest. And far too much of it is plagued by exaggeration, misrepresentations, errors, and obvious bias. In Part 5 of this series, I critiqued Cole Hawkins’ 1998 PhD dissertation. Here, I’m going to untangle some of Lepczyk’s own PhD work: Landowners and cat predation across rural-to-urban landscapes, published in 2003.

The Study

In this study, surveys were distributed across three southeastern Michigan landscapes (rural, suburban, and urban) corresponding to established breeding bird survey (BBS) routes. [2] Among the survey questions:

“If you or members of your household own cats that are allowed access to the outside, approximately how many dead or injured birds a week do all the cats bring in during the spring and summer months (April through August) (0, 1, 2–3, 4–5, 6–7, 8–9, 10–15, 16–20, more than 20)?”

Based on 968 surveys returned from 1654 private landowners (a decent response rate of 58.5%), Lepczyk et al. conclude:

“Across the three landscapes there were ~800 to ~3100 cats, which kill between ~16,000 and ~47,000 birds during the breeding season, resulting in a minimum of ~1 bird killed/km/day.”

Increasing Uncertainty

How do Lepczyk and his collaborators arrive at these figures? It’s not entirely clear, actually. Despite numerous attempts, I’ve been unable to follow all of their calculations. However, using their data, I developed my own estimate: 1,119 outdoor cats, 511 of which were reported to be successful hunters.

Using this figure, I then summed across all three landscapes the birds killed or injured, plus those killed or injured by non-respondents’ hunting cats (based on the ratio of hunters to outdoor cats owned by respondents, or about 50%). The resulting estimate is 15,856 birds killed over the 22-week breeding season—close to the low estimate suggested by Lepczyk et al., but just a third of their maximum.

So, why the discrepancy?

One reason is that, at least for some of their estimates, Lepczyk et al. assumed that every landowner who didn’t respond to the survey owned outdoor cats. This, despite their survey results, which indicated that only about one-third of landowners fell into this category.

But the authors go further, generating predation estimates based on pure speculation, specifically that “non-respondents have 150% the number of outdoor cats as respondents.” [2] It should be noted that Lepczyk et al. also ran another scenario in which non-respondents had half the outdoor cats as did respondents—but, again, in both cases they assume that every non-respondent owned outdoor cats.

As a result of this approach, the authors end up in some strange territory: the estimated number of cats owned by non-respondents (based on the assumptions described above) far exceeds the number owned by respondents—by more than a two-to-one margin, in some cases. If the greatest impacts are going to be attributable to non-respondents, then what’s the point of doing the survey in the first place? There are accepted methods by which one can manage uncertainty—statistical analysis, confidence intervals, and the like. What Lepczyk et al. have done serves just one purpose: to inflate apparent predation rates.

Skewed Distributions

In addition to the flaws described above, there are some fundamental errors in the way the authors handle their data. Like so many others, Lepczyk et al. ignore the fact that their data is not normally distributed:

- Lepczyk et al. use the average number of birds killed/cat to calculate the total number of bids killed for each of the three landscapes. As I discussed previously), this is a highly positively skewed distribution—using a simple average, therefore, greatly overestimates the cats’ impact (by as much as a factor of two).

- A similar error is made when the authors use an average to describe the number of outdoor cats owned by each landowner. Again, because this is a skewed distribution, their use of a simple average exaggerates the extent of predation.

- The two inflated figures described in (1) and (2) are multiplied together, further inflating estimated predation rates.

Barratt has suggested that “median numbers of prey estimated or observed to be caught per year are approximately half the mean values, and are a better representation of the average predation by house cats based on these data.” [3] Accounting for the first point alone, then, my estimate is reduced to 8,000 birds killed over the 22-week breeding season.

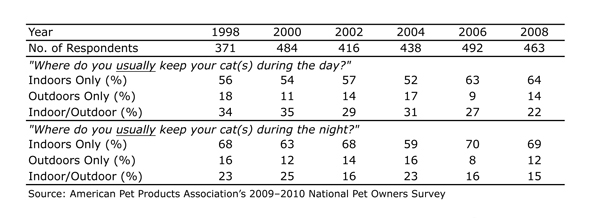

Accounting for the second point is somewhat trickier. For one thing, we don’t know what constitutes an outdoor cat here—the survey simply asked respondents if they owned cats “that are allowed access to the outdoors.” [2] However, we do know the results of a 2003 survey, which indicated that nearly half of the cats with outdoor access were outside for two or fewer hours a day. And 29% were outdoors for less than an hour each day. [4] Although these figures almost certainly reflect owners in urban and suburban landscapes more than those in rural landscapes, it’s clear that a simple yes-or-no question on the subject is insufficient. Indeed, such a question will invariably overestimate the number of “outdoor cats”—which in turn overestimates predation rates.

This, coupled with the error inherent in using a simple average, pushes predation estimates lower. And the third point reduces those estimates further still. Taken together, these corrections could put my estimate closer to 4,000 birds. More important, the upper estimate proposed by Lepczyk et al.—47,000 birds—could easily be 10 times too high.

The Small Print

Despite their inflated figures, Lepczyk et al. suggest—rather absurdly, in light of the substantial flaws described above—that perhaps their estimates are actually too conservative:

“One caveat to our study is that landowners may have underestimated the number of cats they allow access to the outside. Such a result was found in a similar study of landowners in Wisconsin (Coleman and Temple, 1993).” [1] (Note: After reviewing “Rural Residents’ Free-Ranging Domestic Cats: A Survey,” [5] I’ve found no evidence of such a result.)

“… we found that a very common volunteered response among landowners that had no outdoor cats was that either their neighbors owned outdoor cats or that feral cats were present in the vicinity of their land… [suggesting] that at least some landowners under reported or chose not to report the number of outdoor cats they owned.”

But what about their reports of birds brought home killed or injured—how trustworthy were those? After all, the survey (mailed during the first week of October) asked respondents to recall the number of birds their cat(s) brought home April through August. Surely, there was a lot of guesswork involved. In fact, David Barratt found this kind of guesswork to overestimate predation rates. In a study published five years prior to “Landowners and Cat Predation,” Barratt concluded, “predicted rates of predation greater than about ten prey per year generally over-estimated predation observed.” [3]

The two studies cannot be compared directly for a number of reasons, but by way of comparison, the average predation rate used by Lepczyk et al. is approximately 31 birds/cat for the 22-week breeding season. Using Barratt’s work, in which the “heaviest” six continuous months correspond to about 58% of yearly prey totals, [6] I converted this to a yearly rate of 53 birds/cat/year. Barratt has shown that the actual predation rate, at this level, is less than half the rate predicted by cat owners. In other words, predictions of 50 birds/year generally correspond to catches closer to 25 birds/year.

While Lepczyk et al. emphasize the potential for under-estimating predation levels, they never consider the risk of over-estimating these levels—or their most obvious potential source of error: landowners’ recollections of birds killed. The authors question respondents’ reports of outdoor cats, but accept without question their reports of birds injured or killed over the previous six-month period. And, as Barratt indicated, such reports can be inflated by a factor of two or more!

Something else I find troubling comes, of all places, from the Acknowledgements section. Among those thanked “for helpful and constructive reviews” are American Bird Conservancy (ABC) president George Fenwick and Linda Winter, director of ABC’s Cats Indoors! campaign. It’s not clear how Fenwick and Winter contributed to the final paper, but their involvement on any level raises questions about possible bias. Certainly, Winter has credibility issues when it comes to “research” about the impact of free-roaming cats on birds, as I’ve already described (see also pp. 18–24 of TNR Past present and future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement [7]).

* * *

The same year Lepczyk’s paper was published, the American Veterinary Medicine Association held an Animal Welfare Forum “devoted to the management of abandoned and feral cats.” [8] In attendance were more than 200 veterinarians, animal control officials, wildlife conservationists, and animal advocates—each with a different perspective on feral cats in general and TNR in particular.

In welcoming this diverse group, then-President-Elect Bonnie Beaver recognized the range of contentious issues before them:

“Feral cats evoke hot debates about ecological issues, individual cat welfare, human responsibilities, intercat disease transmission, humaneness, zoonosis control, and management and dissolution of unowned cats.” [8]

Amidst the “hot debate,” though, Beaver was optimistic:

“We will not always agree, but we will come away with increased knowledge and a renewed commitment to work for the welfare of all the animals with which we share the earth” [8]

While I tend to share Beaver’s optimism, I think the debate is hurt—if not derailed entirely—by the publication of research aimed not at increasing our collective knowledge, but rather at supporting a particular position. Like Cole Hawkins’ dissertation, “Landowners and Cat Predation” is, at best, an interesting pilot study for subsequent work. And yet, it’s widely—and uncritically—cited in the feral cat/TNR literature. Longcore et al., for example, refer to it as “evidence [indicating] that cats can play an important role in fluctuations of bird populations,” [9] despite the fact that Lepczyk et al. don’t actually address the issue of bird populations at all. More recently, Dauphiné and Cooper use the inflated predation rate suggested by Lepczyk et al. (along with rates proposed by other researchers) to arrive at their “billion birds” figure. [10]

The method employed in “Landowners and Cat Predation”—asking owners of cats to recall the number and species of birds over the previous six-month period—invites overestimation from the very outset. Lepczyk et al. then inflate these numbers through both careless (e.g., using averages to describe skewed data) and deliberate (e.g., assuming all non-respondents owned cats—perhaps 50% more than respondents did) means. Rather than getting us any closer to the truth about cat predation, this study only obscured it further.

Worse, it’s been packaged and sold—and subsequently “bought”—as rigorous science, thereby giving it an undeserved legitimacy. Such efforts are impediments to knowledge and understanding—and therefore, to progress.

References

1. Lepczyk, C.A., et al., “What Conservation Biologists Can Do to Counter Trap-Neuter-Return: Response to Longcore et al.” Conservation Biology. 2010. 24(2): p. 627-629.

2. Lepczyk, C.A., Mertig, A.G., and Liu, J., “Landowners and cat predation across rural-to-urban landscapes.” Biological Conservation. 2003. 115(2): p. 191-201.

3. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by house cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. II. Factors affecting the amount of prey caught and estimates of the impact on wildlife.” Wildlife Research. 1998. 25(5): p. 475–487.

4. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545.

5. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., “Rural Residents’ Free-Ranging Domestic Cats: A Survey.” Wildlife Society Bulletin. 1993. 21(4): p. 381–390.

6. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by House Cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. I. Prey Composition and Preference.” Wildlife Research. 1997. 24(3): p. 263–277.

7. Berkeley, E.P., TNR Past present and future: A history of the trap-neuter-return movement. 2004, Bethesda, MD: Alley Cat Allies.

8. Kuehn, B.M. and Kahler, S.C. The Cat Debate. JAVMA Online 2004 November 27, 2009 [accessed 2009 December 24]. http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/jan04/040115a.asp.

9. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap–Neuter–Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894.

10. Dauphiné, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2010. p. 205–219.