It’s difficult to imagine now but when I started this blog—10 years ago Monday—I worried that I’d soon run out of material to write about. Not only is there no shortage of material, but these days—when facts are up for grabs and media accounts are prone to false equivalencies cultivated in the name of “balance”—Vox Felina’s mission seems more urgent than ever.

Something else that hasn’t changed over the past 10 years: the protectionist practices of editors green-lighting the publication of badly flawed research.

Perhaps it’s oddly appropriate, then, that the impetus for this post is the same one that prompted the blog’s inaugural post—and, indeed, the blog itself. Once again, my response to an article was quickly rejected by a journal.

Authors of the article, which was published recently in Animal Conservation, boldly claim that “pet cats around the world have an ecological impact greater than native predators but concentrated within ~100 m of their homes.”

Perhaps “bold” isn’t even the right word here. After all, the authors didn’t even document predation in any real sense. Instead, they asked survey participants to recall what sort of prey their cats brought home in the past and how often.

This was only the beginning. Through a series of analytical blunders, the authors quickly inflated their predation estimates by a factor of 10 or more.

The worst of it, though, was their conclusions about “ecological impact.” One would imagine that to arrive at such a conclusion, researchers would need to have a reasonably good understanding of the animals (or plants) being affected. Here, the authors didn’t even mention which species were affected—never mind the extent to which that was case.

Lacking empirical evidence, they attempt to make their case via proclamation. And it worked, at least as far as the journal’s reviewers and editorial staff were concerned.

My letter in response (see below), on the other hand, was promptly batted away. As the journal’s editorial office explained, “the key references are out of date and many of the arguments are purely speculative rather than the result of re-analysis.”

Purely speculative?

This from some of the same individuals who published an article all about the “ecological impact”—on no species in particular. Based entirely on the recollection of pet owners. The underlying analysis of which ignores previous research findings and violates the basic tenets of descriptive statistics. All of which escaped the attention of the paper’s 13 co-authors, as well as the journal’s reviewers and editorial staff.

As I say, Vox Felina’s mission seems more urgent than ever.

My letter to Animal Conservation

In their recently published article, “The small home ranges and large local ecological impacts of pet cats,” Kays et al. [1] conclude that “pet cats around the world have an ecological impact greater than native predators but concentrated within ~100 m of their homes.” For the curious reader, there is a lot to unpack here.

The reference to “ecological impact” (a term the authors use no fewer than 18 times) alone raises several questions. These impacts are presumed to be direct, the result of predation. But which species are affected, and to what extent? In what context? Without such specifics (as a starting point anyhow, setting aside for the moment any possible indirect effects—positive or negative—complex trophic interactions, etc.), such a sweeping claim is at best conjecture.

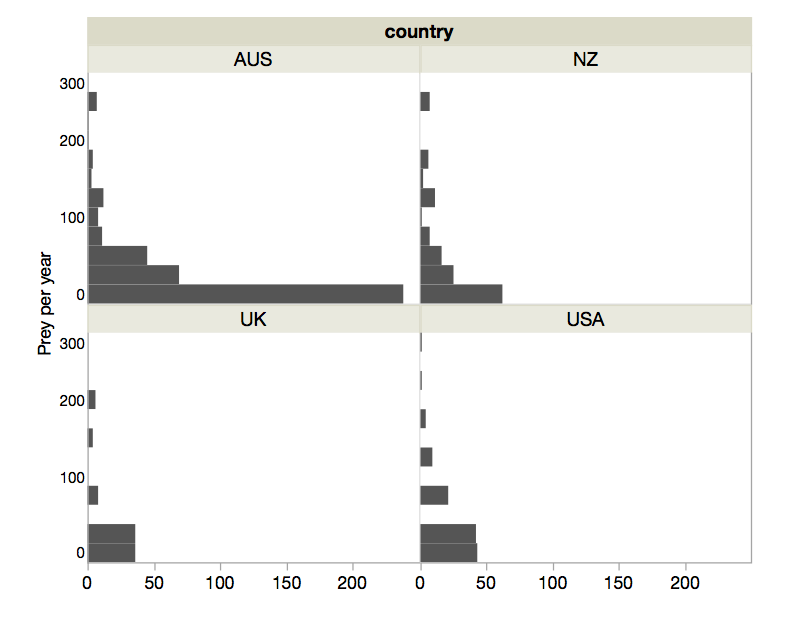

The authors’ claim is further undermined by weaknesses in their analysis, which overlooks multiple key factors. There is, for example, overwhelming evidence that prey return data are highly skewed, with relatively few cats returning numerous prey items while most cats return relatively few [see, for example, 2–6]. Indeed, the data compiled by Kays et al. [1] confirms this, with roughly 51% of cats bringing home no prey (Fig. S5). As Barratt [3] reported, “median numbers of prey estimated or observed to be caught per year are approximately half the mean values, and are a better representation of the average predation by house cats based on these data.” By using a mean predation rate, then, Kays et al. [1] effectively inflated by a factor of two the true level of predation occurring among their study cats.

Histograms summarizing survey responses regarding prey returned by pet cats (Fig. S5 from “The small home ranges and large local ecological impacts of pet cats”).

Barratt [3,7] also observed that predation rates estimated by 143 suburban Canberra cat owners (214 cats total) were, generally speaking, more than double those based on actual prey return data. Several years later, McDonald et al. [8] observed a similar tendency in a smaller study of 38 cats owners in two UK villages (86 cats total). The predation rate reported by Kays et al. [1] is based on a survey of cat owners, not actual prey return data. This suggests that the tendencies observed by Barratt [3] and McDonald et al. [8] likely apply to their findings as well, thereby doubling again the cats’ true predation rate.

Kays et al. [1] then apply “an adjustment factor for animals killed but not eaten (multiplied by 1.2 or 3.3).” However, the higher value (i.e., 3.3) was based solely on observations of cats successfully (or not) hunting small mammals. Specifically, Kays and DeWan [9] observed 31 attempted hunts (by 12 cats), eight of which “resulted in a capture (all small mammals, 26% capture rate)” (emphasis mine). Even setting aside the shortcomings associated with such a small sample, it should be clear that applying this adjustment factor to all prey items is quite inappropriate.

Combining these factors, the resultant predation estimates reported by Kays et al. [1] are very likely inflated by an order of magnitude, thereby challenging the authors’ assertion that “the density of cats yields levels of predation 2–10 times that which would be expected due to wild carnivores” [1]. The comparison strikes me as peculiar, not least because wild carnivores are relatively scarce (certainly compared to domestic cats) within 100 m of most homes. More to the point, though, there is still the question of “ecological impact”—home range and overall predation estimates alone tell us little about the cats’ impact. Again, to make such a determination, we need to know much more about the species being hunted and various key characteristics (e.g., abundance, densities, reproductive capacity, population trends, etc.); Kays et al. [1] do not even provide a breakdown by taxa.

In a 1936 Journal of Mammalogy article, Paul Errington [10] argued that “any study of the house cat intended thoroughly to divulge its ecological status would have to answer not only the question of what the cat eats, but the actual effect its preying may have upon the species in question” (emphasis mine). The “burden of proof” is no different 84 years later. However, the conclusions drawn by Kays et al. [1] are based not on “actual effects,” only vague predation estimates— which, as I’ve pointed out, are grossly inflated. It’s difficult, therefore, to see how the publication of this paper contributes much of value to the body of literature.

On the other hand, it’s not at all difficult to imagine how “The small home ranges and large local ecological impacts of pet cats” will be used to shape policies regarding the management of free-roaming cats (owned and unowned alike), already a highly controversial topic [see, for example, 11–13]. Indeed, its accompanying media release [14] quickly gave rise to the headlines “Killer Kitties?” [15] and “GPS Study Shows Outdoor Cats Have Oversized Effect on Neighborhood Wildlife” [16]. Another related article claims that “pet cats… can cause ecological mayhem” [17]. This is a lot of hype for a study that didn’t actually document predation—never mind its impact. Just as the underlying research has done little to advance our knowledge of the subject, its promotion in the mainstream media has done little to advance fact-based public discourse.

References

- Kays, R.; Dunn, R.R.; Parsons, A.W.; McDonald, B.; Perkins, T.; Powers, S.A.; Shell, L.; McDonald, J.L.; Cole, H.; Kikillus, H.; et al. The small home ranges and large local ecological impacts of pet cats. Animal Conservation 2020, n/a.

- Churcher, P.B.; Lawton, J.H. Predation by domestic cats in an English village. Journal of Zoology 1987, 212, 439–455.

- Barratt, D.G. Predation by house cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. II. Factors affecting the amount of prey caught and estimates of the impact on wildlife. Wildlife Research 1998, 25, 475–487.

- Woods, M.; McDonald, R.A.; Harris, S. Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain. Mammal Review 2003, 33, 174–188.

- Tschanz, B.; Hegglin, D.; Gloor, S.; Bontadina, F. Hunters and non-hunters: skewed predation rate by domestic cats in a rural village. European Journal of Wildlife Research 2011, 57, 597–602.

- Bruce, S.J.; Zito, S.; Gates, M.C.; Aguilar, G.; Walker, J.K.; Goldwater, N.; Dale, A. Predation and Risk Behaviors of Free-Roaming Owned Cats in Auckland, New Zealand via the Use of Animal-Borne Cameras. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2019, 6, 205.

- Barratt, D.G. Predation by House Cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. I. Prey Composition and Preference. Wildlife Research 1997, 24, 263–277.

- McDonald, J.L.; Maclean, M.; Evans, M.R.; Hodgson, D.J. Reconciling actual and perceived rates of predation by domestic cats. Ecology and Evolution 2015, n/a-n/a.

- Kays, R.W.; DeWan, A.A. Ecological impact of inside/outside house cats around a suburban nature preserve. Animal Conservation 2004, 7, 273–283.

- Errington, P.L. Notes on Food Habits of Southwestern Wisconsin House Cats. Journal of Mammalogy 1936, 17, 64–65.

- Marra, P.P.; Santella, C. Cat Wars: The Devastating Consequences of a Cuddly Killer; Princeton University Press: Princeton, N.J., 2016;

- Wolf, P.J.; Schaffner, J.E. The Road to TNR: Examining Trap-Neuter-Return Through the Lens of Our Evolving Ethics. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2019, 5, 341.

- Wolf, P.J.; Rand, J.; Swarbrick, H.; Spehar, D.D.; Norris, J. Reply to Crawford et al.: Why Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) Is an Ethical Solution for Stray Cat Management. Animals 2019, 9.

- Kulikowski, M. Keeping Cats Indoors Could Blunt Adverse Effects to Wildlife. North Carolina State University News 2020.

- Sommer, L. Killer Kitties? Scientists Track What Outdoor Cats Are Doing All Day. All Things Considered 2020.

- Machemer, T. GPS Study Shows Outdoor Cats Have Oversized Effect on Neighborhood Wildlife. SnartNews (Smithsonian Magazine) 2020.

- Losos, J. “Cat Tracker” study reveals the secret wanderings of 900 house cats. Domesticated (National Geographic) 2020.

Is this the same study? Or yet another? I don’t believe the claims. I have had cats all my life and they don’t kill like the article claims.

https://www.npr.org/2020/04/18/820953617/the-killer-at-home-house-cats-have-more-impact-on-local-wildlife-than-wild-preda

Happy Anniversary!!! 10 years of helping us navigate the research landscape with all its landmines.

Many Headbutts,

–Paula in San Francisco

Yes, same study.

I have looked after both pet cats and numerous feral cat colonies for over 25 years and have never seen the type or degree of predation being claimed over and over again; the fact is unless a cat or any animal is actually starving and no other food source is available they may be forced to seek out and kill prey; having said that it needs to be recognized that both pet and feral cats are amazingly adaptive to their environments and know how to co-exist with other species, including wildlife; and yes this is a fact even though we know cats are very territorial! this “fake science” is just a part of so much other “fake news” we are constantly bombarded with by the mentally and culturally lazy both in the media and much of the general population; the ability to perform honest investigative research with intelligent and critically analytic minds is a rarity; this is even evident in the midst of the coronavirus crisis with feeble attempts to implicate our animals and even make domestic pets victims of human stupidity and arrogance.

Thank you, Paula! And many thanks for your tireless efforts!

For the past 25 years, I have been the manager of a 50 cat feral colony. All of the cats are neutered/spayed/vaccinated and fed and watered two times per day. They also receive Veterinary care whenever it is needed.

I have video of the cats freely eating side by side with the local birds (they are all friends now because no one is hungry!) and yet I still get complaints about the colony and the bird killing that is happening.!

I just went through a rouge wildlife experience this last summer where she came and started trapping cats at night. It took me a few days to figure out what was going on and luckily all of the cats were saved and brought back to the colony.

The whole event backfired on the wildlife person since the County is always up to date on my colony. The end result was a new commitment by the County to provide feral cat “fixing” days in the outer areas of the County.

Thank you, Paul, for all you continue to do. I have watched all of your efforts for the last 10 years and it has always made me so happy to know that someone is out there trying to help these innocent animals besides me!

I guess in this new political era everyone is beginning to think they can just “make it up as they go” and say anything they want in order to get headlines. Let’s hope this all stops soon.

Sally Slichter

The Feral Cat Sanctuary (now on YouTube)

We Have to Stop Them From Blaming Cats, Feral or Otherwise

While some wildlife groups may use media attention to speculate that cats are causing species loss, leading biologists, climate scientists, and environmental watchdogs all agree: endangered species’ fight for survival rests in our own hands.

Focusing on cats diverts attention from the far more dangerous impact of humans. Too many media stories sidestep these realities to focus on sensational issues like cats’ imagined impact on birds. But cats have been a natural part of the landscape for over 10,000 years—that has not changed. What has changed in that time is how we have re-shaped the environment to suit 21st century human needs—at a great cost to the other species that share our ecosystem. Our direct impact on our environment is without a doubt the number one cause of species loss.

Make no mistake—habitat loss is the most critical threat to birds. With this exponential human population growth comes massive use of natural resources and rampant development: industrial activity, logging, farming, suburbanization, mining, road building, and a host of other activities. The impact on species from habitat destruction, pollution, fragmentation, and modification is alarming. According to the World Watch Institute, “people have always modified natural landscapes in the course of finding food, obtaining shelter, and meeting other requirements of daily life. What makes present-day human alteration of habitat the number one problem for birds and other creatures is its unprecedented scale and intensity.”

Human activities are responsible for up to 1.2 billion bird deaths every year. Nearly 100 million birds die annually from collisions with windows; 80 million from collisions with automobiles; 70 million from exposure to pesticides. Millions of birds are intentionally killed by U.S. government-sponsored activities each year.

The human population continues to grow, threatening other species. Exponential population growth has left little land untouched by human development. In America alone, the population grew by 60 million people between 1990 and 2010, and experts predict we will add 23 million more people per decade in the next 30 years.

Killing cats will not save wildlife. Studies have shown cats to be mainly scavengers, not hunters, feeding mostly on garbage and scraps. When they do hunt, cats prefer rodents and other burrowing animals. Studies of samples from the diets of outdoor cats confirm that common mammals appear three times more often than birds. Additionally, scientists who study predation have shown in mathematical models that when cats, rats, and birds coexist, they find a balance. But when cats are removed, rat populations soar and wipe out the birds completely.

Some wildlife organizations and media outlets continue to quote scientific studies that have been proven inaccurate. A careful analysis of the science concludes there is no strong support for the viewpoint that cats are a serious threat to wildlife.

Although human civilization and domestic cats co-evolved side by side, the feral cat population was not created by humans. Cats have lived outdoors for a long time. In the thousands of years that cats have lived alongside people, indoor-only cats have only become common in the last 50 or 60 years—a negligible amount of time on an evolutionary scale. They are not new to the environment and they didn’t simply originate from lost pets or negligent animal guardians. Instead, they have a place in the natural landscape.