A pair of Eastern Bluebirds in Michigan, USA. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons and Sandysphotos2009

As I sift through my growing collection of studies, news stories, press releases, and anything else relevant to the free-roaming cats/TNR debate, it’s not unusual for me to be diverted by a seemingly minor item—a claim, interpretation, or reference that simply doesn’t sit right with me. (The subsequent investigation of which helps explains the almost alarming rate at which the collection continues to grow.) Sometimes these diversions snowball, taking on a momentum all their own and, ultimately, evolve into their own blog post(s). Others remain largely in the background—overshadowed by more pressing issues—but are too compelling to be ignored for long.

This was the case with some comments Lepczyk et al. made about “two species of conservation concern” in their 2003 paper “Landowners and Cat Predation Across Rural-to-Urban Landscapes,” [1] which I discussed some time ago. The study, in which surveys were distributed across three southeastern Michigan landscapes (rural, suburban, and urban) corresponding to established breeding bird survey (BBS) routes, asked respondents to recall the number of birds their cat(s) brought home April through August 2000. Among the authors’ conclusions:

“The fact that both Eastern Bluebirds and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds were listed [among those killed by cats] indicates that some species of concern are being captured.” [1]

Eastern Bluebirds

Of the 137 birds (representing an estimated 23 species) identified by landowners (approximately one-third were not identified), six (4.4%) were Eastern Bluebirds. What piqued my curiosity was not the tally itself, but the authors’ subsequent comment that “the location of the three landscapes represents an area of Michigan where the species is rarest and not always identified on bird atlas survey routes.” [1]

Wait a minute. The people conducting bird counts along these routes rarely, if ever, locate Eastern Bluebirds—but the cats that live nearby managed to find at least six of them over the course of just five months? Where Lepczyk et al. see reason for concern, I see reason for (cautious) optimism: There are, as the cats demonstrated, more Eastern Bluebirds than we thought!

Just to be clear: I don’t mean to dismiss conservation concerns for uncommon or rare species. Nor am I criticizing the efforts of the many dedicated professionals and volunteers responsible for bird counts. But in trying to reconcile these seemingly contradictory findings, one can’t help but wonder: How many birds are there, really?

To find out, I began by consulting The Atlas of Breeding Birds of Michigan, the very source Lepczyk et al. cite, where, sure enough, a map indicates that no more than two Eastern Bluebirds are typically found along survey routes in the southeastern part of the state. Indeed, even in the most abundant parts of Michigan, no more than four of this species are reported. [2] But this atlas was published in 1991, more than 10 years prior to Lepczyk’s dissertation research.

To look at more recent data—and long-term trends—I referred to the website for the North American Breeding Bird Survey, where the survey is explained this way:

“The BBS is a large-scale survey of North American birds. It is a roadside survey, primarily covering the continental United States and southern Canada, although survey routes have recently been initiated in Alaska and northern Mexico. The BBS was started in 1966, and the over 3,500 routes are surveyed in June by experienced birders.”

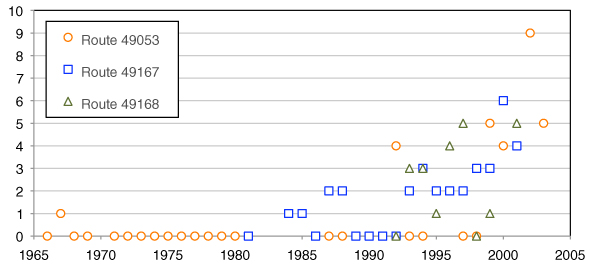

The BBS site allows visitors to investigate trends (spanning roughly 40 years) by species, region, and survey route. What I found for Eastern Bluebirds along the three routes employed by Lepczyk et al. (49053, 49167, and 49168) was rather surprising. In all three cases, the abundance of Eastern Bluebirds trends upward—in some cases dramatically.

BBS Data: Eastern Bluebirds for Three Michigan Routes (adapted from North American Breeding Bird Survey website)

Route 49053 is of particular interest for a couple reasons. First of all, it is the only one of the three for which data going back to the BBS’s inception is available, allowing the best long-term perspective. Secondly, the increase in Eastern Bluebird abundance corresponds almost perfectly to publication of The Atlas of Breeding Birds of Michigan. Between 1991 and 2000 (the year Lepczyk was conducting his research), the picture changed considerably.

The other two routes—to a lesser degree, certainly—also exhibit notable increases. Why Lepczyk referred to the Atlas rather than to this more recent data is unclear.

Bird Counts

It’s important to recognize that bird counts are not intended to quantify, in any absolute sense, the number of birds in a particular area, a point made clear on the BBS website:

“The survey produces an index of relative abundance rather than a complete count of breeding bird populations.”

In addition, the use of roadside surveys has been criticized for its potential biases. Roadside habitats may not reflect—and/or may change at rates different from—an area’s overall habitat, for example. [3] Also, a number of factors affect an observer’s ability to detect or identify a particular species. Some—sight, hearing, and training, and even clothing color, for example—are associated with the surveyors, while others (e.g., plumage, body size, coloration, and density) have to do with the birds being surveyed. [4] Rosenstock et al. suggest that such impediments raise serious questions about index counts in general:

“Measures of relative abundance derived from index counts… represent an uncertain, confounded combination of detectability and density. Given these weaknesses, index counts should not be expected to provide reliable information or a valid basis for inference.” [4]

All of which makes weighing the six Eastern Bluebirds in Lepczyk’s study against those detected along the survey routes a dodgy proposition. (Dodgier still is the more expansive claim made by Longcore et al. that Lepczyk’s work is “evidence indicat[ing] that cats can play an important role in fluctuations of bird populations.” [5])

House Sparrows

To reiterate, I’m not discounting conservation concerns for rare or protected species (the Eastern Bluebird, it should be noted—and Lepczyk et al. acknowledge—is neither “extremely rare” nor a “species of state or national concern.” [1]) I’m merely pointing out some of the complexities involved in trying to connect predation levels of one species to population levels of another.

Which brings me back to The Atlas of Breeding Birds of Michigan, where I discovered an interesting twist in this story. The Eastern Bluebird, it seems, probably peaked in Michigan during the late 1800s.

“A gradual decline occurred in the early 1900s as the House Sparrow advanced, and favorite nesting places such as wooden fenceposts and old apple orchards were eliminated.” [2]

As it turns out, House Sparrows were at the top of the list in Lepczyk’s study, making up 38% of the identified species of birds taken by cats.

“Although the species group of Sparrows could not be broken down into species, it is very likely that the dominant species observed was the House Sparrow (Passer domesitcus). Sparrows were also the most commonly observed depredated species found in England and Australia [6, 7].” [1]

While I’m not prepared to suggest that the cats’ heavy predation of House Sparrows is responsible for the increasing numbers of Eastern Bluebirds, perhaps it’s not as far-fetched as it sounds. Similar assertions have been made regarding the role of cats in the larger ecosystem (though such claims are rarely in defense of the cats).

Nature’s interconnectedness rarely makes for punchy sound bites or bumper sticker aphorisms. Then, too, such complex relationships are often overlooked, ignored, or dismissed simply because they don’t fit cleanly into one’s argument.

Literature Cited

1. Lepczyk, C.A., Mertig, A.G., and Liu, J., “Landowners and cat predation across rural-to-urban landscapes.” Biological Conservation. 2003. 115(2): p. 191-201.

2. Brewer, R., McPeek, G.A., and Adams, R.J., The atlas of breeding birds of Michigan. 1991, East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

3. Keller, C.M.E. and Scallan, J.T., “Potential Roadside Biases Due to Habitat Changes along Breeding Bird Survey Routes.” The Condor. 1999. 101(1): p. 50-57.

4. Rosenstock, S.S., et al., “Landbird Counting Techniques: Current Practices and an Alternative.” The Auk. 2002. 119(1): p. 46-53.

5. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap–Neuter–Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894.

6. Churcher, P.B. and Lawton, J.H., “Predation by domestic cats in an English village.” Journal of Zoology. 1987. 212(3): p. 439-455.

7. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by House Cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. I. Prey Composition and Preference.” Wildlife Research. 1997. 24(3): p. 263–277.