Once again, the American Bird Conservancy is using scare tactics to gain support for their long-standing witch-hunt against free-roaming cats, this time suggesting a connection between TNR and rabies exposure. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention demonstrate no such connection.

Maybe the folks at the American Bird Conservancy were simply feeling left out, what with all the attention the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been getting for their participation in The Wildlife Society’s upcoming feral cat workshop.

You know, all dressed up (tired talking points in hand) and nowhere to go.

With just a day to spare, ABC announced that senior policy analyst Steve Holmer would be participating in the 2nd Annual World Rabies Day Webinar, apparently using the occasion—as is ABC’s habit—to trot out all the usual anti-TNR propaganda.

According to a media release from ABC, Managed Cat Colonies and Rabies was to be “one of 28 presentations being aired in over 70 countries.” I was unable to tune into Holmer’s presentation, but ABC’s announcement suggests I didn’t miss much: “Feral cat colonies bring together a series of high risk elements that result in a ‘perfect storm’ of rabies exposure.”

Put into context, though, the rabies threat posed by “feral cat colonies” is more of a tempest in a teacup.

ABC, CDC, and TWS

“While cats make up a small percentage of rabies vectors,” argues Holmer, “they are responsible for a disproportionate number of human exposures.” As the media release explains:

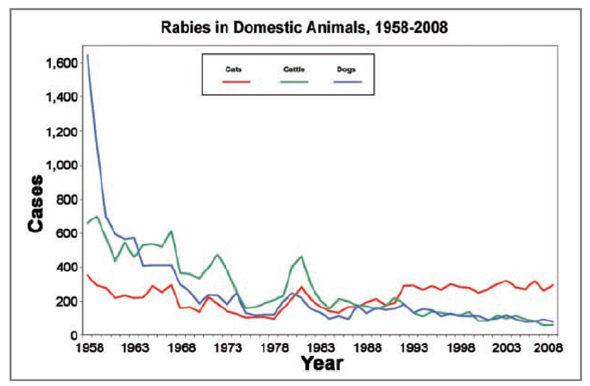

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most people are exposed to rabies due to close contact with domestic animals such as cats and dogs. Although dogs historically posed a greater rabies threat to humans, dog-related incidents have become less frequent in recent decades, dropping from 1,600 cases in 1958 to just 75 in 2008. Meanwhile, cases involving cats have increased over the same period with spikes of up to 300 cases in a single year.

Here, ABC is, once again, not telling us the whole story—beginning with their source. It turns out this paragraph—along with other portions of their release—were lifted verbatim from The Wildlife Society’s Rabies in Humans and Wildlife “fact sheet” (PDF). TWS attributes the figures to a 2009 report of CDC data published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (which includes the graph below).

“State health authorities have different requirements for submission of specimens for rabies testing,” note the authors, “therefore, intensity of surveillance varies.” [1]

“Because most animals submitted for testing are selected because of abnormal behavior or obvious signs of illness, percentages of tested animals with positive results in the present report are not representative of the incidence of rabies in the general population. Further, because of differences in protocols and submission rates among species and states, comparison of percentages of animals with positive results between species or states is inappropriate.” [1, italics mine]

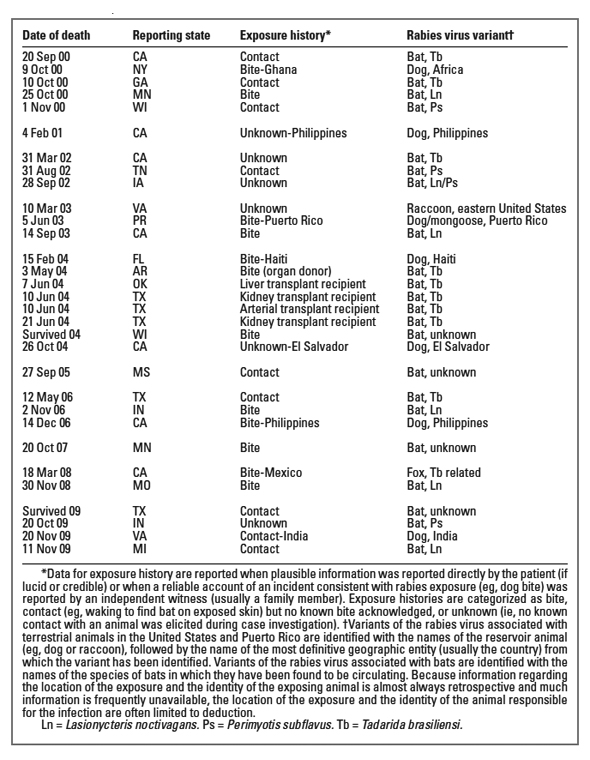

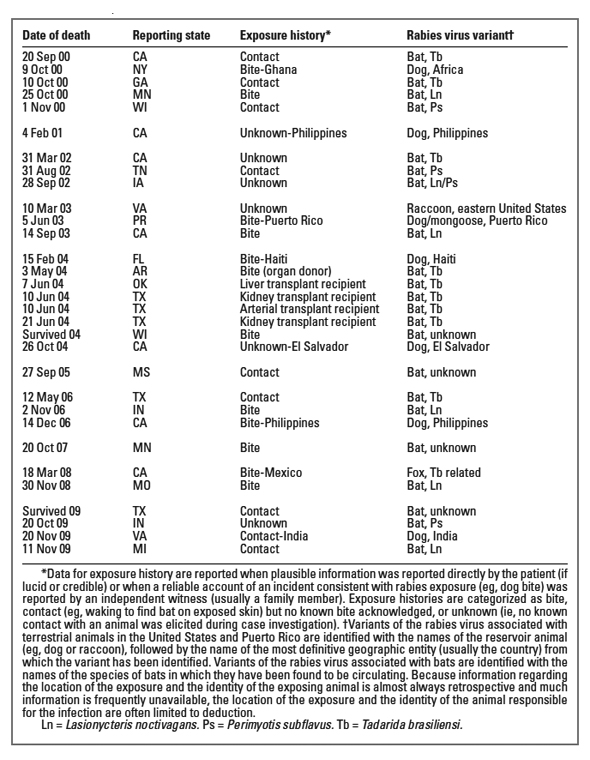

Comparing rabies cases in dogs and cats, as TWS—and, by extension, ABC—have done, misrepresents the actual threat posed by cats. Indeed, as “Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2009” makes clear (see table below), no human case of rabies reported between 2000 and 2009 was linked to a cat.

As one of my colleagues astutely observed, “You are more likely to be executed by Rick Perry than die from rabies contracted from a cat.”

[Note: As I’ve demonstrated previously, TWS’s “fact sheets” aren’t any better than ABC’s media releases when it comes to, well, facts. In Rabies in Humans and Wildlife, TWS suggests that treatment for people exposed to rabies “can cost $7,000 or more; every year, the United States spends approximately $300 million on rabies prevention.” [2]

Among the sources cited by TWS is the CDC—which paints a very different economic picture, suggesting that “a course of rabies immune globulin and five doses of vaccine given over a 4-week period typically exceeds $1,000,” and pointing out that the annual expenditures for rabies prevention “include the vaccination of companion animals, animal control programs, maintenance of rabies laboratories, and medical costs, such as those incurred for rabies postexposure prophylaxis.”

If ABC isn’t going to do their own homework, then they should at least look for a trustworthy source.]

TNR: Barrier to Rabies Transmission

“Managed colonies teach feral cats to associate with humans,” says Holmer/TWS, “and while most people will not interact with wildlife, especially animals displaying erratic behavior, cats are perceived as domestic and approachable.”

In an e-mail to me earlier this week, Merritt Clifton editor of Animal People, dismissed several of Holmer’s assertions, describing TNR as “a very useful tool in fighting rabies.”

“Neuter/return feral cat population control, including vaccination, is in truth a very effective rabies control measure, as I know firsthand, because I was personally involved in the introduction of neuter/return feral cat control to the U.S. in 1991–1992—and it was done as part of a rabies control program.”

“The idea,” says Clifton, “was to see whether neuter/return could turn the feral cat population into a vaccinated barrier between rabid raccoons and free-roaming pet cats.”

“As coordinator of a rabies information hotline for the preceding year, following the arrival in Connecticut of the mid-Atlantic raccoon rabies pandemic, I became one of the three coordinators of an experiment which sterilized and vaccinated 330 feral cats at eight locations in northern Fairfield County, Connecticut.”

The experiment was, Clifton explains, a success. “The only rabid cat ever found near our eight working locations,” he says, “was an unvaccinated house cat who was not normally allowed outside, but escaped and fought with a raccoon before being captured by [a] Town of Monroe animal control officer.” Clifton and his colleagues were, he tells me, “honored by the Town of Monroe Police Department for our accomplishment in keeping rabies from spreading beyond raccoons. The certificate is above my desk right now.”

“To date,” Clifton continues, “there has never been even one case of rabies in the U.S. among cats who were part of a managed neuter/return program, coordinated with a humane society or animal control agency. Of the 32 instances of rabid cats in the U.S. reported by ProMed since 2005, 11 involved feral cats, and several others involved found kittens [and] cats of indeterminate status, but none were part of a neuter return/program.”

[Note: The apparent discrepancy between CDC and ProMed figures are, Clifton tells me, easily explained: “ProMed reports outbreaks, not individual cases.”]

Vaccinations

For Holmer, incorporating the rabies vaccine into standard TNR protocol—as is done in many locations—is insufficient.

“Even when they are vaccinated when first trapped, re-trapping cats to revaccinate can be problematic as the cats become wary of the traps. There is also typically not the funding or infrastructure among the colony feeders to repeatedly re-trap cats to administer vaccines.”

In fact, boosters are probably unnecessary. Julie Levy, Maddie’s Professor of Shelter Medicine at the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine—and one of this country’s foremost experts on feral cats—suggests, “Even a single dose of rabies vaccination provides years of protection against rabies infection.”

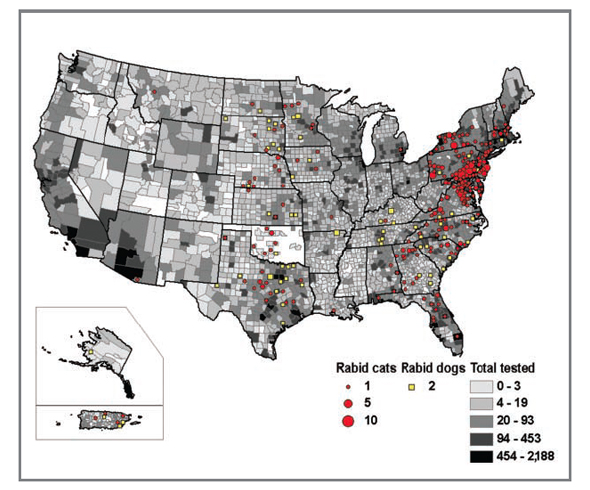

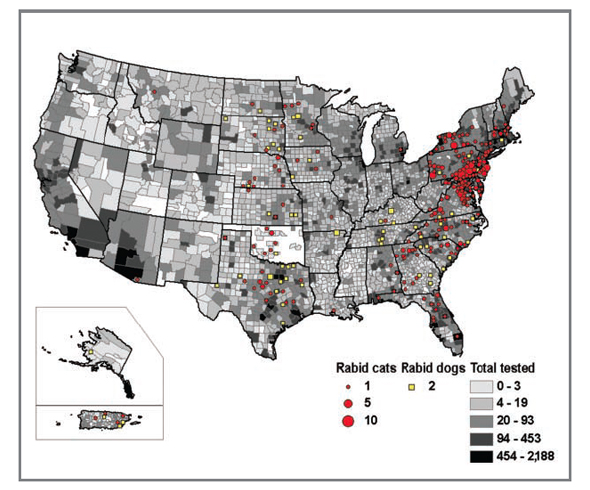

When it comes right down to it, initial vaccinations are probably unnecessary, too, in much of the country. As the authors of the 2009 rabies surveillance report—referring to the map shown below—point out, “Most (81.0 percent) of the 300 cases of rabies involving cats were reported from states where raccoon rabies is enzootic, with two states (Pennsylvania and Virginia) accounting for nearly a third of all rabid cats reported during 2009.” [3]

If ABC is truly concerned about the public health threat posed by “feral cat colonies,” why withhold such critical information? Because their “perfect storm” media release has nothing whatsoever to do public health. Or science, for that matter. It’s just another feeble attempt to gain support for their long-standing witch-hunt against free-roaming cats.

And to add to the fear-mongering, ABC now suggests that TNR actually increases the number of stray, abandoned, and feral cats.

“Peer reviewed studies have shown that over time, cat colonies increase in size, the result of the inability to neuter or spay all the cats and the dumping of unwanted cats at the colony sites by callous pet owners. The result is a large number of unvaccinated cats.”

Just 10 months ago, though, ABC was telling a rather different story. Authors of The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation suggest, “few colonies managed under this system shrink.” [4] Either way, ABC is ignoring compelling evidence that TNR can indeed reduce colony size over time—in some cases 16–32 percent, [5] 36 percent, [6] and 66 percent. [7]

• • •

“The increase in the cases of human rabies exposure from feral cats,” argues Holmer, “should be a concern to city and other government officials.”

“This problem will only get worse as managed feral cat colonies grow in number because half truths about their impacts and implications on local communities and the environment is accepted by decision makers who mistakenly believe they are receiving full disclosure.”

If Holmer’s looking for half-truths and partial disclosures, he needn’t look any further than ABC’s most recent piece of propaganda—the most insidious element of which is merely implied. One might easily get the impression that ABC has a plan to reduce the population of stray, abandoned, and feral cats—a feasible alternative to TNR.

In fact, there is no such plan.

That’s ABC’s dirty little secret (one they share with TWS and USFWS). And that’s what should be a concern to city and other government officials.

Literature Cited

1. Blanton, J.D., et al., “Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2008.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2009. 235(6): p. 676–689. www.avma.org/avmacollections/rabies/javma_235_6_676.pdf

2. n.a., Problems with Trap-Neuter-Release. 2011, The Wildlife Society: Bethesda, MD. http://joomla.wildlife.org/documents/cats_tnr.pdf

3. Blanton, J.D., Palmer, D., and Rupprecht, C.E., “Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2009.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2010. 237(6): p. 646–657. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/pdf/10.2460/javma.237.6.646

4. Lebbin, D.J., Parr, M.J., and Fenwick, G.H., The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation. 2010, London: University of Chicago Press.

5. Natoli, E., et al., “Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy).” Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2006. 77(3-4): p. 180–185. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TBK-4M33VSW-1/2/0abfc80f245ab50e602f93060f88e6f9

www.kiccc.org.au/pics/FeralCatsRome2006.pdf

6. Nutter, F.B., Evaluation of a Trap-Neuter-Return Management Program for Feral Cat Colonies: Population Dynamics, Home Ranges, and Potentially Zoonotic Diseases, in Comparative Biomedical Department. 2005, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC. p. 224. http://www.carnivoreconservation.org/files/thesis/nutter_2005_phd.pdf

7. Levy, J.K., Gale, D.W., and Gale, L.A., “Evaluation of the effect of a long-term trap-neuter-return and adoption program on a free-roaming cat population.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(1): p. 42-46. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.42

8. Yoshino, K. (2010, January 17). A catfight over neutering program. Los Angeles Times, from http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-feral-cats17-2010jan17,0,1225635.story

![]()