Masts of the Rugby Radio Station transmitter, Warwickshire, England. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Sreejithk2000.

Recent research suggests that collisions with buildings and communication towers have no significant effect on bird populations. These findings raise additional questions about the often-implied connection between predation by free-roaming cats and declining bird numbers.

![]()

According to the American Bird Conservancy, 300 million to 1 billion birds are killed each year in “collisions with glass on buildings, from skyscrapers to homes.” As many as 50 million more are killed annually by communication towers.

Yet, according to a study published last September in the open-access, online publication PLoS ONE, “this conspicuous source of mortality has had no discernible effect on long-term population dynamics among North American landbirds.” [1]

“At worst,” suggest authors Todd Arnold and Robert Zink, conservation biologists from the University of Minnesota, “collision mortality could be described as an added burden for populations already in decline for other reasons.” [1]

Which would seem to be, if not good news for the folks at ABC, then at least news. (Even solutions “that can greatly reduce avian collision mortality at manmade structures,” warn the researchers, “will not halt population declines among North American migratory birds.” [1])

So, why is there no mention of this study—published nearly six months ago—on the ABC website?

I suspect it will never appear there—or in any ABC publication. And they’re certainly not going to mention it to the media—too many awkward questions about contradictory assertions, resource allocation, and the like. After all, this is an organization that prides itself on using “the best available science” to shape policy.

(To be clear: Arnold and Zink are not opposed to “the deployment of simple design solutions that can greatly reduce avian collision mortality at manmade structures,” [1] despite the rather dire results of their analysis.)

The Study

To better understand potential population-level impacts, Arnold and Zink compared “long-term records of avian mortality from communication towers and urban buildings… with population estimates and trend data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey.” [1] The relative vulnerability of various species (188 in the case of communication towers, 147 for buildings) was quantified by comparing the proportion of birds killed in collisions with towers and/or buildings with their proportion in the overall bird population.

Species with very high collision mortalities relative to their abundance were dubbed “super colliders,” while species with very low instances of collisions relative to their numbers were dubbed “super avoiders.”

The spread between the two extremes is astonishing. Bay-breasted warblers, for example, were found to be 236 times more likely to collide with towers than would be predicted by chance alone (but are nevertheless considered a species of Least Concern). Horned larks, on the other hand, are 688 times more likely to avoid the same towers.

Fascinating work! What caught my eye, though, was the authors’ suggestion that their analysis technique would be appropriate for assessing “many poorly quantified conservation threats [including] house cat predation.” [1]

Future (Hypothetical) Study

Curious, I contacted Arnold, asking him how one would go about conducting such a study. Surely, obtaining an accurate count of mortalities due to predation is far more complicated than tallying mortalities due to man-made structures (itself, no trivial undertaking).

In fact, the greatest challenge, suggests Arnold, is not the data collection or subsequent analysis.

“In order to do the scientific study that you asked about, it’s necessary to approach it objectively, and I’d worry that anybody tackling this issue would be in one camp or the other, and the study really demands an impartial referee. A possibly better alternative would be to get members of both sides to agree in a mediated discussion what would constitute a valid study of the issue, and how such a study would be designed, implemented, and interpreted.”

Fair enough. Still, though: if implementation and interpretation pose particular challenges, the design of the study is actually fairly straightforward. “To apply the approach that we used for tower and building collisions,” Arnold says, “you would need to assemble a large data set on what species of birds are killed by cats.”

“It would probably take a large network of citizen scientists to accumulate a database on species composition of cat-killed wildlife; they would need to be people who had frequent and regular access to one or more cats—so, cat owners, cat monitors, and cat stewards who would agree to participate on a long-term basis. It would be important that sampling wasn’t driven by spectacular events (e.g., a cat owner ignores several non-descript House Sparrows that their cat brings home, and only submits information when a colorful Northern Cardinal gets killed). Conversely, you’d need to worry about people who might report only the boring and common things and fail to report when a rare or well-loved bird is killed because they are ashamed or fear backlash from the bird-loving public.”

Proper identification of each species would, of course, be critical. This, says Arnold, could be done using digital photos or by collecting remains (a method often employed in predation studies [2] and [3] and [4]).

“The study would have to continue until several thousand birds had been identified to species (Bob Zink and I worked with data sets that were a minimum of about 5,000 dead birds). From the mortality records, one would first identify the species that were most vulnerable to cats by comparing their proportion in the cat-kill data to their expected proportion based on population estimates. So, say for example, that juncos and American robins were 5.2 and 3.2 percent of the mortality records, but only 1.3 and 1.6 percent of the total bird population, then they’d be 4 and 2 times more vulnerable to cats than expected by chance. Other species would be less vulnerable than expected by chance. This part of the study would identify which species of birds were most vulnerable to predation by cats, and a priori I’d expect to see that ground-feeding birds like juncos and robins were more vulnerable, as well as urban- and suburban-adapted birds like robins, starlings, chickadees, etc.”

As Arnold and Zink point out in their paper, “total body counts reveal little about relative mortality risk for each species”—a fact often overlooked or ignored by those trying to link predation by cats to declining bird populations. And so, “the final—but critical—step” in our hypothetical study, says Arnold, “is to ask: Does this mortality factor matter do bird populations?”

“It obviously matters to the individuals that were killed, but given that 40–50 percent of the fall bird population is probably not going to be alive one year later, the focus here has to be on long-term population dynamics. And so, the final step would involve correlating the measure of vulnerability to cat predation from the first step with long-term population trends for these same species. If one finds that cat predation rates are not correlated with bird population trends, then it’s time to stop vilifying cats for bird declines (with the important caveat that it might still be important for one or two endangered/threatened species). If one finds that cat predation rates are negatively correlated with bird population declines, then it suggests that cats might be an important limiting factor of birds populations (with the important caveat that it might be due to some other unmeasured factor that is also correlated with cat predation).”

What We Already Know

Unfortunately, I’m in no position to undertake the study Arnold describes. And, in any case, am (unapologetically) in “one camp or the other.” (That said, I’d jump at the chance to be part of the aforementioned “mediated discussion.”)

On the other hand, there’s already plenty of research suggesting that predation does not necessarily result in population-level impacts. In The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour, for example, Mike Fitzgerald and Dennis Turner thoroughly reviewed 61 predation studies, concluding rather unambiguously: “We consider that we do not have enough information yet to attempt to estimate on average how many birds a cat kills each year. And there are few, if any studies apart from island ones that actually demonstrate that cats have reduced bird populations.” [5]

Also: it’s well-known that predators—cats included—tend to prey on the young, the old, the weak and unhealthy. Indeed, at least two research studies have investigated this phenomenon in great detail. In one, researchers comparing the fat reserves of birds killed by cats to those of birds killed through non-predatory events (e.g., collisions with windows or cars) found that “mean fat scores evident in the cat-killed birds… were sufficiently low that these individuals were likely to have had poor long-term survival prospects.” [6]

In another study, researchers found that songbirds killed by cats tend to have smaller spleens than those killed through non-predatory events, leading them to conclude that “avian prey often have a poor health status.” [7]

As the UK’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds notes: “It is likely that most of the birds killed by cats would have died anyway from other causes before the next breeding season, so cats are unlikely to have a major impact on populations.” [8]

(Frank Gill makes this very point in the third edition of Ornithology: “With some conspicuous exceptions… predators don’t limit or regulate the bird populations on which they prey. Instead, they take weak, sick, and young birds, many of which are part of the surplus that exceeds locally limiting food supplies.” [9] When it comes to cats, however, Gill considers “managed feral cat colonies [to be] potentially a serious threat to local bird populations.”)

• • •

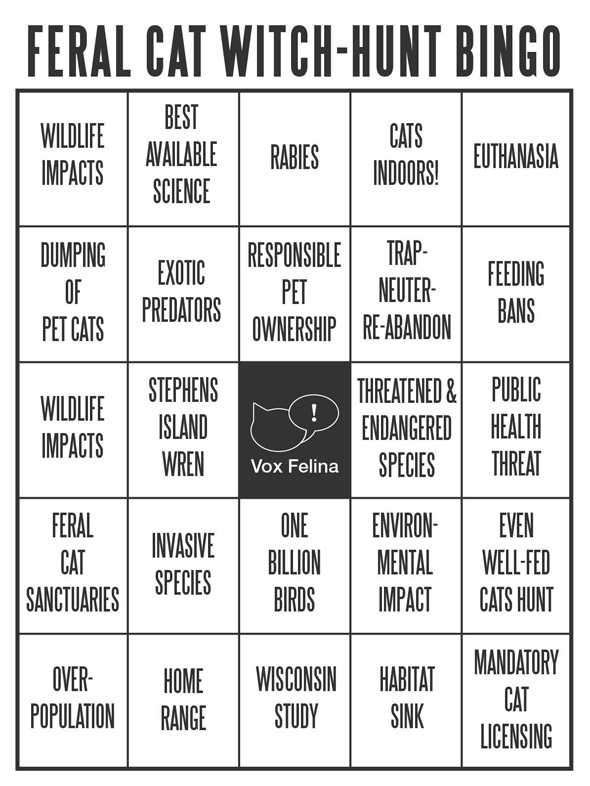

Granted, the studies referenced above are no substitute for the one Arnold describes. And I don’t expect ABC to “stop vilifying cats for declining bird populations” anytime soon.

Nevertheless, Arnold and Zink’s findings ought to make it more difficult for ABC (or any other organization blaming cats for declining bird populations) to continue using cats as scapegoats. After all, even using the figures cited by ABC, it seems quite likely that collisions with buildings and communication towers are responsible for more bird deaths than are cats.* And the man-made structures are taking out healthy individuals.

Of course, as Arnold notes in his e-mail, bird species vulnerable to man-made structures may not be vulnerable to predation by cats, and those vulnerable to predation by cats may not be vulnerable to collisions. Still, taken together, all of this research begs the question: If building- and tower-collisions aren’t having population-level impacts, how likely is it that free-roaming cats are?

Which is exactly what I asked Darin Schroeder, ABC’s Vice President of Conservation Advocacy, and Steve Holmer, their Director of the Bird Conservation Alliance. That was three weeks ago.

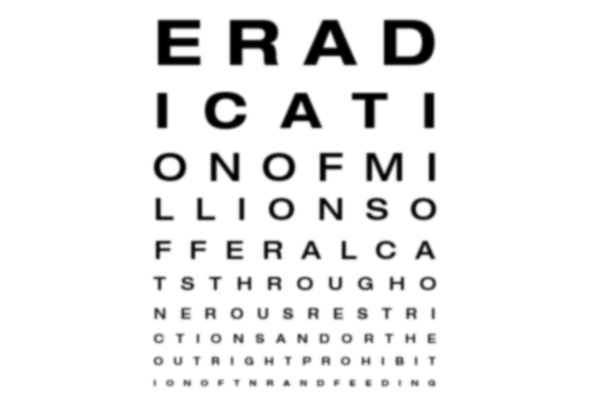

*According to The American Bird Conservancy’s Guide to Bird Conservation, “532 million birds [are] killed annually by outdoor cats.” [10] Though far less than the “one billion birds” sometimes cited by TNR opponents, [11] ABC’s “estimate” is based on some dubious assumptions.

Thanks to my friends at Alley Cat Allies for bringing Arnold and Zink’s paper to my attention.

Literature Cited

1. Arnold, T.W. and Zink, R.M., “Collision Mortality Has No Discernible Effect on Population Trends of North American Birds.” PLoS ONE. 2011. 6(9): p. e24708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0024708

2. Churcher, P.B. and Lawton, J.H., “Predation by domestic cats in an English village.” Journal of Zoology. 1987. 212(3): p. 439-455. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1987.tb02915.x

3. Woods, M., McDonald, R.A., and Harris, S., “Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain.” Mammal Review. 2003. 33(2): p. 174-188. http://www.mammal.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=256:domestic-cat-predation-on-wildlife&catid=51:survey-reports&Itemid=289

4. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by House Cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. I. Prey Composition and Preference.” Wildlife Research. 1997. 24(3): p. 263–277.

5. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

6. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: Is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86–99. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bsc/ibi/2008/00000150/A00101s1/art00008

7. Møller, A.P. and Erritzøe, J., “Predation against birds with low immunocompetence.” Oecologia. 2000. 122(4): p. 500–504. http://www.springerlink.com/content/ghnny9mcv016ljd8/

8. n.a. (2011) Are cats causing bird declines? http://www.rspb.org.uk/advice/gardening/unwantedvisitors/cats/birddeclines.aspx Accessed October 26, 2011.

9. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 3rd ed. 2007, New York: W.H. Freeman. xxvi, 758 p.

10. Lebbin, D.J., Parr, M.J., and Fenwick, G.H., The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation. 2010, London: University of Chicago Press.

11. Dauphine, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2009. p. 205–219. http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/pif/pubs/McAllenProc/articles/PIF09_Anthropogenic%20Impacts/Dauphine_1_PIF09.pdf