In April, Conservation Biology published a comment authored by Christopher A. Lepczyk, Nico Dauphiné, David M. Bird, Sheila Conant, Robert J. Cooper, David C. Duffy, Pamela Jo Hatley, Peter P. Marra, Elizabeth Stone, and Stanley A. Temple. In it, the authors “applaud the recent essay by Longcore et al. (2009) in raising the awareness about trap-neuter-return (TNR) to the conservation community,” [1] and puzzle at the lack of TNR opposition among the larger scientific community:

“…it may be that conservation biologists and wildlife ecologists believe the issue of feral cats has already been studied enough and that the work speaks for itself, suggesting that no further research is needed.”

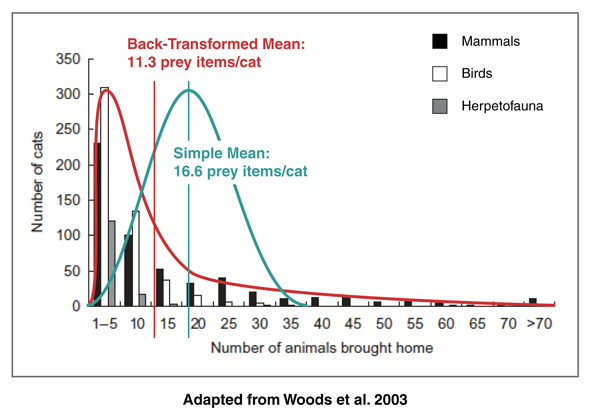

In fact, “the work”—taken as a whole—is neither as rigorous nor as conclusive as Lepczyk et al. suggest. And far too much of it is plagued by exaggeration, misrepresentations, errors, and obvious bias. In Part 3 of this series, I discussed the distinction between compensatory and additive predation. Here, I’ll focus on how feral cat/TNR researchers often misuse averages to characterize skewed distributions, and how that error overestimates the impact of free-roaming cats on wildlife.

Something’s Askew

When a data set is skewed, it is inappropriate to use the mean, or average, as a measure of central tendency. The mean should be used only when the data set can be considered normal—the familiar bell curve. As Woods et al put it:

“the simple average number of animals brought home is not a useful measure of central tendency because of the skewed frequency distribution of the numbers of prey items brought home…” [2]

Studies of cat predation routinely reveal a positively skewed distribution; a few cats are responsible for many kills, while many of the cats kill few, if any, prey. So when researchers use the mean to calculate the total number of prey killed by cats in a particular area, they overestimate the cats’ impact.

How common is this? Very [see, for example, 3-9]. Of the many cat predation studies I’ve read, only a few [2, 10, 11] properly account for the skewed nature of this distribution. And others [12-17] often take these inflated figures at face value—as evidence of the impact cats have on wildlife. Published repeatedly, the erroneous estimates take on an undeserved legitimacy.

The proper method for handling skewed distributions involves data transformations, the details of which I won’t go into here. The important point is this: in the case of a positively skewed distribution, the back-transformed mean will always be less than the simple mean of the same data set.

Big Deal

Depending on the particular distribution, the difference between the simple mean and the back-transformed mean can be considerable. Let’s use the 2003 study by Woods et al. [2] to illustrate. In the case of mammals killed and returned home by pet cats, the back-transformed mean was 28.3% less than the simple mean. Or, put another way, the simple mean would have overestimated the number of mammals killed by 39.5%. Similarly, when all prey items were totaled (as depicted in the illustration above), the simple mean would have overestimated the total number off all prey (mammals, birds, herpetofauna, and “others”) by 46.9%.

On the other hand, the figures for birds appear to break the rule mentioned above. In this case, the back-transformed mean (4.1) is actually a bit higher than the simple mean (4.0). How can this be? In order to log-transform the data set, Woods et al. had to first eliminate all the instances where cats returned home no prey—you can’t take the logarithm of 0. So, they were actually working with two data sets. Now, the second data set—which includes only those cats that returned at least one prey item—is also highly positively skewed. As a point of reference, its simple mean was approximately 5.6 birds/cat, which, compared to the back-transformed mean, is an overestimation of 37.5%.

By now, it should be apparent that log-transformed means have another important advantage over simple means: because you have to eliminate those zeros from the data set, you are forced to focus only on the cats that returned prey home—which, of course, is the whole point of such studies! And in the case of this study, Woods et al. found that 20–30% of cats brought home either no birds or no mammals. And 8.6% of the cats brought home no prey at all over the course of the study.

Transforming a data set (and then back-transforming its mean) is simpler than it sounds, but Barratt offers a useful alternative, rule-of-thumb method (one echoed by Fitzgerald and Turner [18]):

“…median numbers of prey estimated or observed to be caught per year are approximately half the mean values, and are a better representation of the average predation by house cats based on these data.” [10]

So, whereas Dauphiné and Cooper (and others) suggest increasing such estimates by factors of two and three (“predation rates measured through prey returns may represent one half to less than one third of what pet cats actually kill…” [14]), they should, in fact, be reducing them by half.

Cat Ownership

There are other instances in which simple averages are used to describe similarly skewed distributions—with similar results. That is, they overestimate a particular characteristic—and not in the cats’ favor.

Cat ownership, for example, is not a normal distribution. Many people own one or two cats; a few people own many cats. This is precisely what Lepczyk et al. found in their 2003 study:

“The total number of free-ranging cats across all landscapes was 656, ranging from 1 to 30 per landowner…” [6]

In fact, about 113 (I’m estimating from the histogram printed in the report) of those landowners owned just one cat apiece. About 70 of them owned two cats. Only one—maybe two—owned 30 cats. And yet, Lepczyk et al. calculate an average of 2.59 cats/landowner (i.e., 656 cats/253 landowners who allow their cats outdoors), thereby substantially overestimating cat ownership—and, in turn, predation rates (which calculations are based upon the average number of cats/landowner).

Lepczyk et al. are not the only ones to make this mistake; several other researchers have done the same. [4, 5, 7-9]

Outdoor Access

The amount of time cats spend outdoors is also highly positively skewed, as is apparent from the 2003 survey conducted by Clancy, Moore, and Bertone. [19] Their work showed that nearly half of the cats with outdoor access were outside for two or fewer hours a day. And 29% were outdoors for less than an hour each day.

Among those researchers to overlook the skewed nature of this distribution are Kays and DeWan, who calculate an average of 8.35 hours/day. This greatly overestimates potential predation, and leads them to conclude—erroneously—that the actual number of prey killed by cats was “3.3 times greater than the rate estimated from prey brought home,” [9] as was discussed previously.

Compound Errors

Clearly, these errors are substantial—in some cases, doubling the apparent impact of cats on wildlife. Of course the errors are even more significant when one inflated figure is multiplied by another—as when Lepczyk et al. [6] multiply the average number of prey items returned by the average number of outdoor cats per owner. The resulting predation figures may well be four times greater than they should be! (Actually, there are additional problems with the authors’ predation estimates, which I’ll address in a future post).

* * *

The fact that such a fundamental mistake—one a student couldn’t get away with in a basic statistics course—is made so often is shocking. The fact that such errors slip past journal reviewers is inexcusable.

References

1. Lepczyk, C.A., et al., “What Conservation Biologists Can Do to Counter Trap-Neuter-Return: Response to Longcore et al.” Conservation Biology. 2010. 24(2): p. 627-629.

2. Woods, M., McDonald, R.A., and Harris, S., “Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain.” Mammal Review. 2003. 33(2): p. 174-188.

3. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., On the Prowl, in Wisconsin Natural Resources. 1996, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources: Madison, WI. p. 4–8. http://dnr.wi.gov/wnrmag/html/stories/1996/dec96/cats.htm

4. Baker, P.J., et al., “Impact of predation by domestic cats Felis catus in an urban area.” Mammal Review. 2005. 35(3/4): p. 302-312.

5. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86-99.

6. Lepczyk, C.A., Mertig, A.G., and Liu, J., “Landowners and cat predation across rural-to-urban landscapes.” Biological Conservation. 2003. 115(2): p. 191-201.

7. Crooks, K.R., et al., “Exploratory Use of Track and Camera Surveys of Mammalian Carnivores in the Peloncillo and Chiricahua Mountains of Southeastern Arizona.” The Southwestern Naturalist. 2009. 53(4): p. 510-517.

8. van Heezik, Y., et al., “Do domestic cats impose an unsustainable harvest on urban bird populations?“ Biological Conservation. 143(1): p. 121-130.

9. Kays, R.W. and DeWan, A.A., “Ecological impact of inside/outside house cats around a suburban nature preserve.” Animal Conservation. 2004. 7(3): p. 273-283.

10. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by house cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. II. Factors affecting the amount of prey caught and estimates of the impact on wildlife.” Wildlife Research. 1998. 25(5): p. 475–487.

11. Barratt, D.G., “Predation by House Cats, Felis catus (L.), in Canberra, Australia. I. Prey Composition and Preference.” Wildlife Research. 1997. 24(3): p. 263–277.

12. May, R.M., “Control of feline delinquency.” Nature. 1988. 332(March): p. 392-393.

13. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383.

14. Dauphiné, N. and Cooper, R.J., Impacts of Free-ranging Domestic Cats (Felis catus) on birds in the United States: A review of recent research with conservation and management recommendations, in Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics. 2010. p. 205–219

15. Longcore, T., Rich, C., and Sullivan, L.M., “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap–Neuter–Return.” Conservation Biology. 2009. 23(4): p. 887–894.

16. Winter, L., “Trap-neuter-release programs: the reality and the impacts.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1369-1376.

17. Clarke, A.L. and Pacin, T., “Domestic cat “colonies” in natural areas: a growing species threat.” Natural Areas Journal. 2002. 22: p. 154–159.

18. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

19. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545.