On February 25th, the Utah House of Representatives voted rather decisively—44 to 28—in favor of HB 210, which would amend the state’s animal cruelty laws. Whether or not the representatives knew what they were voting for, however, is anybody’s guess.

Listening to the floor debate, one gets the impression there were two—maybe three—different bills up for discussion. Not that House members got any help from sponsor Curtis Oda (R). Indeed, Oda’s rambling, disjointed presentation only muddied the waters further.

Among the bill’s provisions is an exemption for animal cruelty in cases where the individual responsible for harming or killing an animal acted reasonably, in the protection of people or property. Also included—and the source of the greatest controversy—is an allowance for “the humane shooting of an animal in an unincorporated area of a county, where hunting is not prohibited, if the person doing the shooting has a reasonable belief that the animal is a feral animal.”

This Is Not About Cats

Referring to the bad press HB 210 has received over the past few weeks (including a stinging satire on The Colbert Report, which was widely circulated on the Web), Oda was, not surprisingly, defensive.

“It wasn’t about cats; it’s about all animals that are feral—including cats, dogs, pigeons, pigs, whatever it might be… But the cat community has made it a cat issue, so let’s talk cats.”

And talk cats he did.

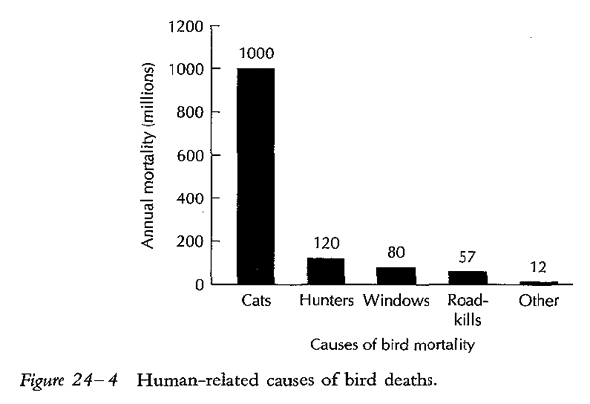

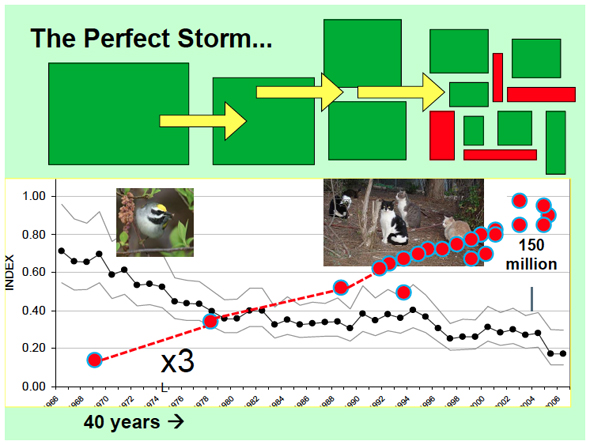

“Let’s get into some of the other reasons why we need some of this… The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—and because it was made into a cat issue, I’m using cats—cites that cats and other introduced predators are responsible for much of the migratory bird loss. Domestic and feral may kill hundreds of millions of songbirds and other avian species every year, roughly 39 million birds annually. They’re opportunistic hunters, taking any small animal available—pheasants, native quail, grouse, turkeys, waterfowl, and endangered piping plovers. Most of these birds are protected species.”

That 39 million figure, of course, comes from the notorious Wisconsin Study, and represents Coleman and Temple’s “intermediate… estimate of the number of birds killed annually by rural cats in Wisconsin.” [1] Nothing more than a “best guess,” as the authors call it, and one based entirely on the predation of a single cat in rural Virginia. [2, 3]

It’s a figure commonly found in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) publications, [4, 5] and on their Website. (Oda’s not the first one to mistake this for an estimate of predation across the country, however; Frank Gill made the same error in his book Ornithology. [6])

Oda’s choice of bird species surely raised a few eyebrows—at least among those who were paying attention. First of all, a number of the birds are hunted in Utah—which would seem to complicate the predation issue significantly (though, of course, hunters are paying for the “privilege” of killing wildlife).

And those “endangered piping plovers” (technically, listed as “Near Threatened”)? According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Website, this “small pale shorebird of open sandy beaches and alkali flats…[apparently, Utah’s salt flats don’t count] is found along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, as well as inland in the northern Great Plains.”

Another obvious blunder: Oda would have us believe that cats are both opportunistic hunters (which they are) but that they also target rare and endangered species. (But again, Oda’s not alone: USFWS made a similar argument in their recent Florida Keys National Wildlife Refuges Complex Integrated Predator Management Plan/Draft Environmental Assessment.

Economic Impact

Once Oda brought up Wisconsin, it seemed almost inevitable that Nebraska, too, would creep into the debate. It didn’t take long.

“The Audubon magazine recently cited a new peer-reviewed paper by University of Nebraska–Lincoln—researchers concluding that feral cats—domestic that live outdoors and are ownerless—in other words, feral—account for $17 billion—that’s billion—in economic loss from predation on birds in the U.S. every year.”

That $17 million dollar figure (which, apparently, was just too good for the National Audubon Society, American Bird Conservancy, and others to pass up) is based on some very dubious math (indeed, the paper notes that birders spend just $0.40 for each bird seen, whereas hunters spend $216 for each bird shot, suggesting, it seems, that dead birds are far more valuable than live birds—a point NAS and ABC, of course, ignored entirely).

The origins of the figure can be traced to two papers by Cornell’s David Pimentel and his colleagues, [7, 8] in which the authors estimate “economic damages associated with alien invasive species.” [8]

Referring to this work, Hoagland and Jin, resource economists at the Marine Policy Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, (using the case of the European green crab to make their point) warn: “There are many reasons to be concerned about the use of these estimates for policymaking.” [9] Among their concerns, are the use of potential rather than actual impacts, and the validity of the underlying science—as well as the overall lack of rigor involved in developing such estimates.

“Heretofore, estimates of the economic losses arising from invasive species have been far too casual. Unfounded calculations of economic damages lacking a solid demonstration of ecological effects are misleading and wasteful.” [9]

Predation Estimates

Oda then tried to put the predation into context:

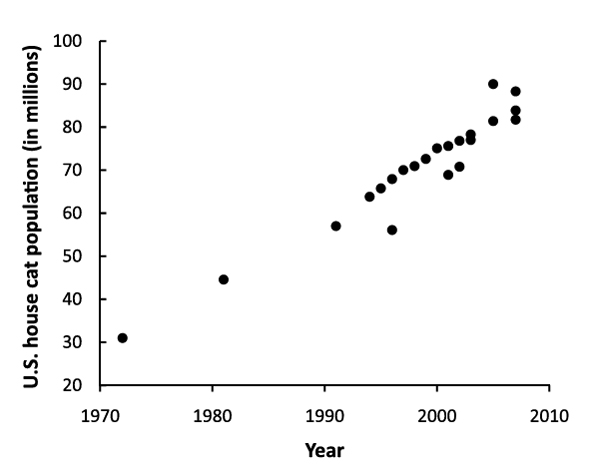

“In Utah alone, if we assume a million households, you can estimate around a third of them have cats—that’s 333,333. If we just add a feral population of at least that many, making it two-thirds of a million—if each cat killed just three birds per year, you can see that the predation is around two million each year.”

Three birds/year is more conservative than what’s used for many back-of-the-envelope estimates, but that doesn’t excuse the flaws in Oda’s calculation—beginning with his suggestion that the number of feral cats in the state equals the number of pet cats. Where’s the evidence?

He’s also assuming that all cats hunt. However, about two-thirds of pet cats don’t even go outside. [10–12]

And then, of course, there’s the issue of impact. Even if Oda’s right about the two million birds, that says nothing about the impact on their populations. Are the birds common? Rare? Healthy? Unhealthy? Etc.

Referring to “Cats and Wildlife: A Conservation Dilemma,” another of the Wisconsin Study papers, [13] Oda continues:

“Nationwide, cats probably kill over a billion mammals and hundreds of millions of birds each year. Worldwide, cats may have been involved in the extinction of more bird species than any other cause except by habitat destruction.”

Again, no mention of impact. And, no mention of where the vast majority of those extinctions took place. According to Gill’s Ornithology:

“Most (119, or 92 percent) of the 129 bird species that have become officially extinct in the past 500 years are island species. Roughly half of these species were exterminated by introduced predators and diseases. The rest were driven to extinction by direct human exploitation and habitat destruction.” [6]

However isolated Utah may seem at times—politically, socially, and culturally—the state is not an actual island.

Trap-Neuter-Return

For an assessment of TNR, Oda turns not to Alley Cat Allies or to the No More Homeless Pets in Utah program, but to David Jessup, Senior Wildlife Veterinarian with the California Department of Fish and Game:

“David Jessup, a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, has written that trap, neuter, and release programs are not working as well as it has been touted. I’ve got packets here talking about that. If anybody wants to see it, they’re welcome to that.”

In fact, Jessup offers little to support his own sweeping claim that, “in most locations where TNR has been tried, it fails to substantially or quickly reduce cat numbers and almost never eliminates feral cat populations” [14] Instead, he refers to a paper by Linda Winter, [15] former director of ABC’s Cats Indoors! campaign—and prolific source of misinformation on the subject of TNR.

Oda continues:

“Releasing feral cats back into the wild is actually an unnatural act. They are unnatural predators that compete [for] food with eagles, hawks, owls, ferrets, etc.”

This last point, it would seem, is a reference to the often-cited work of William George, who suggested that “cats inevitably compete for prey with many of our declining raptors, and therein may lie a serious problem.” [16] It turns out, though, that George’s concerns were largely unfounded, as I’ve discussed previously.

No wonder Oda turned to Jessup and Winter for a TNR primer—the man simply doesn’t have a clue:

“Citizens that want to help are often met with expenses and inconveniences that deter them. Many who monitor TNR colonies are not managing them correctly. I had one lady who said she had more than 100 cats that she had saved with TNR, but kept getting new cats almost weekly. She’d been feeding them more than what they could do on their own, thereby attracting new cats.”

I rather doubt that making it legal to shoot at feral cats will somehow make caretakers’ lives easier. And why, if Oda thinks regular citizens are unable to properly manage a colony of feral cats, is he so sure they’ll be able to properly distinguish a feral cat from a pet in the event they want to shoot it?

Oda’s complaint about feeding feral cats—and the idea that this attracts additional cats—is a common one. Cats are remarkably resourceful, and where there are people, there is food. Better to have them part of a managed colony, where they are sterilized—and often adopted, too—than to be under the radar.

The same argument can be made for the alleged relationship between TNR and the dumping of cats. It’s difficult to imagine that the presence or absence of a nearby TNR program would affect a person’s decision to abandon his/her pet cat(s). (If any studies had demonstrated such a connection, TNR opponents would surely cite them.) And, under the circumstances, isn’t it better that they be “enrolled” in a TNR program than the alternative?

“Releasing is also unfair to the rest of the neighborhood,” argued Oda, “who’s adversely affected.”

“It doesn’t affect just the person monitoring. But the problem is much bigger than TNR only. An unspayed female cat can have up to three litters per year, with an average of five kittens per litter, so as you can see, the problem grows exponentially.”

While unrestricted populations will grow exponentially, Oda’s numbers are ridiculous—probably the foundation for the widely debunked 420,000-cats-in-seven-years-myth.

Still think HB 210 isn’t about cats?

A Little Something for Everybody

At this point, Oda’s presentation moves beyond the bogus science and tired, baseless complaints—and pretty well comes off the rails entirely.

“This bill does not replace TNR, but it’s supposed to work potentially in conjunction with TNR, but we need to make sure everybody uses those TNR programs properly. We do have a serious problem with irresponsible owners, and we can’t make it unreasonable for them to take their animals to shelters and animal control facilities… We need to make things a little bit easier for people to help, not just make it easier for them to—” [lost audio]

How open season on feral cats is “supposed to work potentially in conjunction with TNR” is a mystery—and one Oda didn’t have a chance to clear up. At this point, his colleagues give him just one more minute to wrap things up.

“We just need to make it easier for people to be able to do things the right way, instead of making it so ridiculously expensive and inconvenient—so that it’s easier for them to just take their animals and drop them off anywhere else, whether it be cats or dogs, or whatever it may be. Perhaps down the road we might have to have mandatory licensing for cats. We do that with dogs already and the problem with dogs has diminished substantially.”

Huh?

Are we still talking about the same bill here? HB 210 does nothing at all to address dumping, intake policies at shelters, or licensing. The confusion only worsened as several representatives supporting the bill took to the House floor to make their positions known.

Supporters

Rep. Fred Cox (R), who helped revise the bill, suggested that HB 210 offers a means of controlling the population of feral cats—a complement to TNR programs:

“We spent quite a bit of time reviewing with proposed amendments… We did have the opportunity of listening to a number of individuals speak for and on behalf of various options… You have to decide whether or not it’s a good idea for individuals to purposely release certain animals—sometimes in large quantities into the wild that were not originally designed to be here. There are certain parts of the world that have had problems with this area, and in some cases, we have problems now. This provides us an option. We still have other options that are available—with trap, neuter, and release—those are still on the table. This does not prohibit those methods to be used, but does allow another method to be used.”

For Rep. Lee Perry (R), HB 210 offers a humane approach for dealing with abandoned pets:

“I represent a lot of rural farmers and ranchers, and this bill is critical to them. I can’t have a farmer or rancher going to jail or to prison because they take care of a feral cat or a feral dog that is on their ranch or their farm, that somebody inhumanely took out and dumped out in the middle of western Box Elder County or in western Cache County. When the people go out there and dump their animals, thinking they’re being humane and putting them… out into the wild or onto somebody’s farm, they’re actually harming those animals more than what these farmers or ranchers would be doing in basically being humane, and putting them out of their misery at that point. Because these animals are eventually going to starve to death, in some cases, and die. They’re left in the cold, in the elements. These are usually animals that are meant to be raised in a house, and in a controlled environment. Because of that, I support this substitute bill, and I would ask that the body would support it as well.”

Easily the most interesting account, however, was that of Rep. Brad Galvez (R):

“I had an individual that lives just a few miles west of my home who was basically attacked by a cat—had a cat that scratched him on his hand, and he basically just flung it against the wall. This individual was charged with a third-degree felony.”

A search of several newspapers tells a very different story. Reese Ransom, 85, was actually charged with aggravated animal cruelty—a misdemeanor—when he severely injured a feral kitten. When Ransom picked up the kitten—one of a litter he and his wife had been feeding—to bring it inside:

“It went wild, like cats do,” he said. “It was scratching and biting. It was hanging from my hands with its teeth, so I just pitched it away to get rid of it. It hit the garage and knocked it out.” [17]

According to Ogden’s Standard–Examiner, Weber County Sheriff’s Deputy Bryce Weir witnessed the event. “Weir’s report said Weir got out of his patrol car and walked to the garage, noting the kitten was still alive, but barely moving.” [18]

The kitten was eventually euthanized.

The Animal Advocacy Alliance of Utah pushed for Ransom to be changed with a felony, but were unsuccessful.

But Galvez, who—don’t forget—lives just a few miles east of Ransom, completely misrepresents the facts of the case to his colleagues. There’s no telling whether or not his “interpretation” of events had any bearing on the eventual vote, but it raises questions about the man’s integrity.

Opponents of HB 210

HB 210 had its detractors as well. Among them, Rep. Marie Poulson (D):

“I am… the daughter of a rancher and a cattleman, but have another perspective on this. I realize the threat to cattle of these pests, or feral animals. But, in our particular case, we encourage the population of feral cats, as we have four granaries, and they were some of our best farm workers, and kept down the rodent population. My main problem with this bill is, there’s no designation between what’s considered a feral animal and your beloved house pet. And I think this bill gives license to kill in those areas. My other consideration here is that I have received so many letters from constituents upset by this bill that if I voted for it, I would be considered feral.”

Rep. David Litvack (D) wasn’t buying what Oda and his supporters were selling, especially when it comes to defining feral. “If a person knows that a particular animal is a pet of their neighbor,” explained Oda during his introductory comments, “it’s not feral. If it’s wearing a collar, it’s not feral. If there’s other signs it’s very friendly, obviously it’s not feral.”

Litvack was unmoved:

“I believe it is wrong for us, as a state, to move in the direction where we are having individuals make the decision, the determination on their own (1) what is feral, and (2) now, that they can shoot them, even if it’s only in an unincorporated county. Not a good policy, and, quite frankly, a bit of an embarrassment to the state of Utah.”

Referring specifically to Lines 153 and 154 of the amended bill (“…the humane shooting of an animal in an unincorporated area of a county, where hunting is not prohibited, if the person doing the shooting has a reasonable belief that the animal is a feral animal.”), Rep. Brian King (D) took a similar stance:

“My concern is that we’re providing a loophole in the statute for individuals that want to use this as an opportunity to go out and satisfy [lost audio] they get pleasure from going out and just shooting what are now defined as feral animals just for the pleasure of killing the animal… This is a bill that’s been brought to us now, in its amended form, just today, and we haven’t had a chance to hear from the Humane Society, from other individuals or agencies that have an interest in this. And my concern is that, although I think there is undoubtedly a reasonable need for individuals under certain circumstances—in rural areas, especially—to control feral animal populations that are causing damage, I still have concerns—without more input from those who deal with this, and have really had a chance to think the language through—in voting it out of our body.”

“We spent quite a bit of time reviewing with proposed amendments,” countered Cox. “We did have the opportunity of listening to a number of individuals speak for and on behalf of various options.”

Cox offered no specifics about who was invited to the bargaining table. And it may not have made any difference anyhow—like Oda and Perry, Cox seems to think HB 210 is about feral cat management:

“You have to decide whether or not it’s a good idea for individuals to purposely release certain animals—sometimes in large quantities into the wild that were not originally designed to be here. There are certain parts of the world that have had problems with this area, and in some cases, we have problems now. This provides us an option. We still have other options that are available—with trap, neuter, and release—those are still on the table. This does not prohibit those methods to be used, but does allow another method to be used.”

Rep. Paul Ray (R) responded to King’s concern by comparing TNR to abandonment (an argument perhaps first articulated by Jessup, who refers to TNR as “trap, neuter, and reabandon” [14]):

“It’s against the law to abandon an animal… [TNR practitioners] abandon the animal again. So when we’re talking about getting the perfect language, I’m not sure we can do that because even under the current law we have right now, we have some discrepancies…”

Setting aside the TNR/abandonment issue for the moment, that’s quite a position to take for somebody whose job it is to craft legislation: What we’ve got now isn’t perfect, so why bother?

Oda’s response was no better. “Out in the rural areas,” he said, referring to the concerns about the ambiguity surrounding the term feral, “they know exactly what animals belong in the area, so that’s not even an issue.”

This, I’m sure, was no consolation to Litvack or King.

Shoot First, Ask Questions Later

If you missed the part where the bill’s supporters defend—or even explain—the need for Utahns to be able to shoot feral animals, you’re not alone. I’ve listened to the entire debate at least twice now and still don’t get it.

As Laura Nirenberg, legislative analyst for Best Friends’ Focus on Felines campaign, pointed out to me, the bill’s language already addresses many issues brought up in the debate.

Under HB 210, for example, the crime of animal cruelty requires that “the person’s conduct is not reasonable and necessary to protect: (1) the actor or another person from injury or death; or (2) property from damage or loss if the property is an animal; or other property that is $50 or more in value.” (The $50 threshold seems like too low a bar to me, but it was never mentioned during the floor debate.)

This, it seems, goes an awful long way toward protecting farmers and ranchers who are merely protecting their livestock. And the Reese Ransoms of the world, too. Moreover, there’s already a provision in Utah’s animal cruelty code exempting a “person who humanely destroys any apparently abandoned animal found on the person’s property” (which, strangely, never came up during the HB 210 debate).

Granted, the bill’s amended language does lessen its potential impact on feral cats by restricting “the humane shooting of an animal” to unincorporated areas “where hunting is not prohibited.” Hunting regulations must comply with Utah criminal code, which prohibits the “discharge any kind of dangerous weapon or firearm… without written permission to discharge the dangerous weapon from the owner or person in charge of the property within 600 feet of: a house, dwelling, or any other building; or any structure in which a domestic animal is kept or fed, including a barn, poultry yard, corral, feeding pen, or stockyard.”

Even so, the shooting provision of HB 210 strikes me as essentially indefensible. It’s simply an invitation for senseless cruelty. Representative Litvack is exactly right: “Not a good policy, and, quite frankly, a bit of an embarrassment to the state of Utah.”

• • •

It will be interesting to see what happens when HB 210 moves to the Utah Senate, where, just last week, TNR-friendly SB 57 was passed. Among its provisions:

“This bill… defines a sponsor of a cat colony as a person who actively traps cats in a colony for the purpose of sterilizing, vaccinating, and ear-tipping before returning the cat to its original location; exempts community cats from the three-day mandatory hold requirement; and allows a shelter that receives a feral cat to release it to a sponsor that operates a cat program.”

I encourage readers to listen to the HB 210 debate in its entirety, as it provides a fascinating glimpse of democracy in action—warts and all (including, for example, when Oda responds to the call for a vote with “Meow.”) The SMIL audio file is available here, and the required Real Audio application can be downloaded free here.

Literature Cited

1. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., On the Prowl, in Wisconsin Natural Resources. 1996, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources: Madison, WI. p. 4–8. http://dnr.wi.gov/wnrmag/html/stories/1996/dec96/cats.htm

2. Coleman, J.S. and Temple, S.A., How Many Birds Do Cats Kill?, in Wildlife Control Technology. 1995. p. 44. http://www.wctech.com/WCT/index99.htm

3. Mitchell, J.C. and Beck, R.A., “Free-Ranging Domestic Cat Predation on Native Vertebrates in Rural and Urban Virginia.” Virginia Journal of Science. 1992. 43(1B): p. 197–207. www.vacadsci.org/vjsArchives/v43/43-1B/43-197.pdf

4. USFWS, Migratory Bird Mortality. 2002, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Arlington, VA. http://www.fws.gov/birds/mortality-fact-sheet.pdf

5. USFWS, Perils Past and Present : Major Threats to Birds Over Time. 2003, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Arlington, VA. http://www.fws.gov/birds/documents/PastandPresent.pdf

6. Gill, F.B., Ornithology. 3rd ed. 2007, New York: W.H. Freeman. xxvi, 758 p.

7. Pimentel, D., et al., “Environmental and Economic Costs of Nonindigenous Species in the United States.” Bio Science. 2000. 50(1): p. 53–65. http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1641/0006-3568%282000%29050%5B0053%3AEAECON%5D2.3.CO%3B2?journalCode=bisi

www.tcnj.edu/~bshelley/Teaching/PimentelEtal00CostExotics.pdf

8. Pimentel, D., Zuniga, R., and Morrison, D., “Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States.” Ecological Economics. 2005. 52(3): p. 273–288. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6VDY-4F4H9SX-3/2/149cde4f02744cae33d76c870a098fea

9. Hoagland, P. and Jin, D.I., “Science and Economics in the Management of an Invasive Species.”BioScience. 2006. 56(11): p. 931-935. http://www.mendeley.com/research/science-economics-management-invasive-species-8/

10. Clancy, E.A., Moore, A.S., and Bertone, E.R., “Evaluation of cat and owner characteristics and their relationships to outdoor access of owned cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2003. 222(11): p. 1541-1545. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2003.222.1541

11. Lord, L.K., “Attitudes toward and perceptions of free-roaming cats among individuals living in Ohio.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2008. 232(8): p. 1159-1167. http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_232_8_1159.pdf

12. APPA, 2009–2010 APPA National Pet Owners Survey. 2009, American Pet Products Association: Greenwich, CT. http://www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp

13. Coleman, J.S., Temple, S.A., and Craven, S.R., Cats and Wildlife: A Conservation Dilemma. 1997, University of Wisconsin, Wildlife Extension. http://forestandwildlifeecology.wisc.edu/wl_extension/catfly3.htm

14. Jessup, D.A., “The welfare of feral cats and wildlife.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1377-1383. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15552312

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1377.pdf

15. Winter, L., “Trap-neuter-release programs: the reality and the impacts.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004. 225(9): p. 1369–1376. http://avmajournals.avma.org/doi/abs/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1369

http://www.avma.org/avmacollections/feral_cats/javma_225_9_1369.pdf

16. George, W., “Domestic cats as predators and factors in winter shortages of raptor prey.” The Wilson Bulletin. 1974. 86(4): p. 384–396. http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Wilson/v086n04/p0384-p0396.pdf

17. Miller, J. (2010, June 24). Charge questioned in death-of-kitten case. Standard-Examiner. http://www.standard.net/topics/courts/2010/06/23/charge-questioned-death-kitten-case

18. Gurrister, T. (2010, July 22, 2010). Cruelty charge in West Haven kitten case to be dismissed Standard-Examiner. http://www.standard.net/topics/courts/2010/07/22/cruelty-charge-west-haven-kitten-case-be-dismissed