Opponents of trap-neuter-return are long on rhetoric, but short on alternatives—at least ones they’ll discuss openly.

We just want the cats gone.

Yeah, well, I want a pony.

I don’t actually say that, of course. Not usually, anyhow—in part, because the two wishes are hardly comparable. If I really wanted a pony, I’d simply go buy one (a rescue, of course; or, as an alternative, contact the Bureau of Land Management, which began its most recent brutal roundup of wild horses and burros in Nevada last year). End of story.

“Removing” cats—a euphemistic reference to an often-fatal course of action—on the other hand, is not the end of the story at all (except, as I say, for the particular cats involved). Where there is adequate food and shelter—and island eradication efforts have demonstrated rather dramatically just how little human assistance the domestic cat requires in this regard—there will very likely be cats. If not today, then it’s very likely only a matter of time.

And still, the call for their “removal”—accompanied by this naive wish that such a move will be a one-time occurrence—is, it seems, continuous.

Last week, Loews Hotels in Orlando, FL, made headlines nationally when the self-described “pet-friendly hotel brand” reversed its position on TNR and on-site managed colonies. Among the news stories brought to my attention this week: the Waco, TX, Lions Club is demanding that Heart of Texas Feral Friends, whose volunteers have been sterilizing and caring for cats in a park owned by the Lions Club, discontinue feeding. According to KXXV News, the cat food “could attract bigger animals that could bite children playing at the park.”

In Harvey Cedars, NJ, 51-year-old Mark Rist has been, according to the Asbury Park Press, “charged with feeding feral cats,” the result of a two-month investigation. According to the paper, Rist was feeding 63 cats in one area—despite what Police Chief Thomas Preiser describes as the community’s “ongoing effort to control feral cats.’’ “It has cost the borough over $5,800 in fees to have cats trapped and taken to the animal hospital,” said Preiser. “This is on top of the over $3,000 the borough pays just for animal-control services.’’ (An online petition advocating that the charges be dropped has been started, and has more than 1,650 signatures already.)

And, less than 60 miles away, in Manalapan, NJ, health department officials have announced that they’ll begin trapping a managed colony of cats located at the Bridge Plaza office complex on February 1. As Michael Volovnik, president of the property association, explained to the Asbury Park Press, the cats are using a playground sandbox as a litter box, and could also cause a traffic accident in the complex parking lot. (I thought I’d heard all the “reasons” for killing outdoor cats, but this one’s new to me.)

Take away their food—or the cats themselves—and the problem’s solved, right? End of story.

Um, no. Not even if you click together the heels of your ruby slippers three times, repeating as you do: “We just want the cats gone.”

And yet, this is precisely what TNR opponents would have us believe. In fact, they often go much further. When, for example, the American Bird Conservancy sent a letter (PDF) to the mayors of the 50 largest U.S. cities last October, urging them “to oppose Trap-Neuter-Re-abandon (TNR) programs and the outdoor feeding of cats as a feral cat management option,” their stated objective was to “stop the spread of feral cats.”

How’s that supposed to work, exactly?

Darin Schroeder, ABC’s Vice President for Conservation Advocacy, and author of the letter, hasn’t bothered—either in his original, well-publicized mass-mailing, or in response to my inquiries—to explain the mysterious cause-and-effect relationship underlying the claim. (Or, while we’re at it, ABC’s projections regarding the number of recipients who would surely be alienated by a letter that so grossly insults their intelligence.)

As I’ve pointed out previously, common sense—and science, which ABC claims to have firmly in its camp on this issue—tells us that such policies (assuming they could be enforced, of course) would only drive population numbers upward. (Indeed, there is plenty of evidence from island eradication efforts. On Marion Island, to take one of the more spectacular examples, the population of cats was estimated to be about 2,200 in 1975, just 26 years after they were introduced to the 115-square-mile, barren, uninhabited South Indian Ocean island. [1] If there were any efforts to sterilize these cats, I’ve not read about it. And the only “handouts” they received were “the carcasses of 12,000 day-old chickens” [1] injected with poison, as part of the 19-year eradication program.)

Now, if, as Schroeder claims, there are “well-documented impacts of cat predation on wildlife,” how could the inevitable increase in the free-roaming cat population possibly be a benefit? Or—again, if Schroeder is right about the impacts—be aligned with ABC’s vision of “an Americas-wide landscape where diverse interests collaborate to ensure that native bird species and their habitats are protected, where their protection is valued by society, and they are routinely considered in all land-use and policy decision-making”?

Such contradictions are, as anybody who’s been paying attention has surely noticed, hardly uncommon in ABC’s anti-cat messaging.

ABC didn’t do any better with their letter (this one, more of a low-key affair) to Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar, sent last summer. (DOI oversees the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which, as I’ve pointed out repeatedly, has been an eager, taxpayer-funded participant in the witch-hunt against free-roaming cats.) In that letter, ABC, along with several signatories, aimed to “call [Salazar’s] attention to the threat being posed to wildlife by feral cats.” (Once again, ABC referred to “the well-documented impacts of cat predation on wildlife,” this time citing the work of, among others, former Smithsonian researcher Nico Dauphine, convicted in October of attempted animal cruelty for trying to poison neighborhood cats. It’s not entirely clear, but I have to think the letter was sent just prior to her arrest, after which ABC hasn’t, to my knowledge, expressed the slightest support for Dauphine.)

Signatories to the letter “urge[d] the development of a Department-wide policy opposing Trap-Neuter-Release and the outdoor feeding of cats as a feral cat management option, coupled with a plan of action to address existing infestations affecting lands managed by the Department of the Interior.” (This would include much of the Florida Keys, of course. Regular readers will recall that ABC enthusiastically endorsed the deeply flawed Florida Keys National Wildlife Refuges Complex Integrated Predator Management Plan/Draft Environmental Assessment, issued a year ago.)

This “plan of action” is something I’ve been giving a great deal of thought to for some time now. And not just as it relates to “existing infestations” on DOI-controlled land; I’m interested in the big picture here. These folks are hell-bent on a future in which the feeding of outdoor cats is prohibited, one in which TNR is banned.

What I want to know is this: What happens if they get their way?

Alternatives to TNR?

One might expect that ABC, promoters for 15 years now of Cats Indoors!, would have an answer. Indeed, I brought up the subject during a December 2010 webinar celebrating the launch of their book The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation. “What we recommend,” offered Michael Parr, Vice President of ABC, “as an alternative to [TNR], is not abandoning cats in the first place.”

“Other options would be to house those cats in shelters, or outdoor sanctuaries which could be managed. Clearly, it’s a huge problem, and the solutions to this are going be things we going to have to work together on for a long period of time, but certainly that would be my first reaction to that question.”

After 14 years (at that time) of staunch opposition to TNR, this is the best ABC can do? Well, yes. (One wonders if ABC officials are truly so out-of-touch and/or flat-out delusional that they really think nobody’s noticed.)

The Wildlife Society

ABC is not alone, of course. The Wildlife Society, which signed onto the DOI letter, in its position statement (issued in August 2011) on Feral and Free-Ranging Domestic Cats (PDF), calls for “the humane elimination of feral cat populations,” as well as “the passage and enforcement of local and state ordinances prohibiting the feeding of feral cats.”

And in November, TWS sponsored the USFWS workshop, Influencing Local Scale Feral Cat Trap-Neuter-Release Decisions , at its annual conference. According to TWS, the “workshop [was] designed to train biologists and conservation activists to advocate for wildlife in the decision making process by providing the best available scientific evidence in an effective manner.” (Ah, yes: “best available scientific evidence.” It’s the same expression ABC and USFWS like to throw around. The critical term here is available. It seems all the science contradicting their steady stream of bogus claims is locked in the same filing cabinet, and the key’s been “lost.”)

But TWS hasn’t done any better than ABC when it comes to connecting the dots between our current situation and a future free of feral cats.

When, in his November 14 blog post, TWS Executive Director/CEO Michael Hutchins drifted off-message, conceding that “TNR alone is not the ultimate solution,” (emphasis mine) I used the opportunity to press him on the issue. Referring to the recently issued TWS position statement, I told Hutchins, “it doesn’t seem unreasonable to expect a well-established and influential organization such as TWS to propose a plan to accompany such a vision.”

“On the contrary, it’s exactly what your membership should expect from their leadership—and what those of us who care for the cats you’re targeting demand.”

And Hutchins’ response? Cue the crickets (native species only, of course).

(Hutchins did, however, spend a good deal of time backpedaling: “I haven’t changed my position at all, and neither has The Wildlife Society, an organization now representing more than 10,600 wildlife professionals.” It now appears that the post itself has been modified to reflect his “corrected” position on the subject.)

Urban Wildlands Group

In January 2010, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge handed down an injunction prohibiting the City of Los Angeles from supporting TNR. Under the provisions of the injunction (in its revised version, filed with the court in March 2010), the City, its Board of Animal Services Commissioners, and its Department of Animal Services are prohibited from “promoting TNR for feral cats and encouraging or assisting third parties to carry out a TNR program.” [2]

According to the original petition—filed by the Urban Wildlands Group, Endangered Habitats League, Los Angeles Audubon Society, Palos Verdes/South Bay Audubon Society, Santa Monica Bay Audubon Society, and ABC—implementation of TNR in L.A. “can cause significant adverse environmental impacts by causing proliferation of rats and raccoons and creating water pollution problems.”

It’s important to recognize that the very premise of the petition—brought under the California Environmental Quality Act—is a red herring, nothing more than a roundabout way to go after TNR (in part, by restricting the funding to key organizations integral to L.A.’s various TNR programs). Setting that aside for the moment, though, the question remains: If TNR isn’t the answer, then how are we to reduce the population of stray, abandoned, and feral cats?

Travis Longcore ought to have an answer. Indeed, as head of the Urban Wildlands Group, current president of the Los Angeles Audubon Society, and author of the well-circulated “Critical Assessment of Claims Regarding Management of Feral Cats by Trap-Neuter-Return” (a compilation of cherry-picked “facts,” misrepresentations, and glaring omissions, which I’ve critiqued in some detail), Longcore (who, I suspect, is the same “Travis” whose comment brought Hutchins back from the brink in November) would seem to be the go-to guy on this topic.

In fact, he doesn’t seem to have any plan, either.

In a December 2010 exchange on the Audubon magazine blog, The Perch (in which senior editor Alisa Opar blindly endorsed the infamous University of Nebraska-Lincoln paper as if it were actual research), Longcore twisted himself in a knot avoiding the question.

“You’ve been very straightforward about your desire to see TNR and the feeding of feral cats outlawed.” I wrote. “But then what?”

“I’ve yet to hear from you—or anybody on your side of the issue—spell it out. We all know the cats won’t disappear in the absence of TNR/feeding. We can argue about rates of population growth, carrying capacity, etc.—but let’s keep it simple here. Under your plan, there are these feral cats—an awful lot of them—that no longer have access to the assistance of humans (other than scavenging trash, say). OK, now what?”

Longcore’s response, in a nutshell, advocated for mandatory spay/neuter, and “cat licensing so that cats are no longer treated as second class, disposable pets.” (It’s difficult to see how their wide-scale killing will get them bumped up to first-class, but such illogical leaps have long been the norm among TNR opponents.)

Whatever his misgivings about disclosing a feasible alternative to TNR, Longcore was more than willing to diagnose the mental health of TNR supporters:

“TNR advocates… aren’t actually interested in reducing feral cat numbers. TNR is something that they ‘sell’ to their jurisdiction so that they are allowed to keep feeding ‘their’ cats. They appear to prefer that the problem persist so that they can validate their sense of self worth by being rescuers.”

There’s an irony to Longcore’s allegation, of course. If, as he implies, he and his fellow petitioners are “actually interested in reducing feral cat numbers,” then why not lay out the way forward?

“You failed to answer the question posed,” I pressed.

“Let me rephrase it, then: Throw in mandatory spay/neuter (if and only if adequate low/no-cost S/N is provided to the community—a rarity, as I’m sure you know), as you suggest. And let’s say there are—again, just to simplify matters—no roaming pet cats. The problem remains: many, many feral cats. And even if Animal Control had the resources to round up every one of them that triggers a complaint, it’s a drop in the bucket. And once you’ve outlawed TNR, there’s no way even one of these cats is going to be sterilized. So, the next step here is what, exactly?”

Longcore’s reply, not surprisingly, was a laundry list of “policies needed to control feral cats,” the majority of which—either directly or indirectly—simply lead to more killing: mandatory spay/neuter, pet limits, prohibitions on roaming, and prohibitions of “feral cat feeding unless on feeder’s property, or with permission of property owner and nearby owners/residents.” Oh, and “euthanasia” (not to be confused with euthanasia). Among the non-lethal solutions: “adoption or other nonlethal removal (e.g. the few sanctuary spaces),” and “outdoor enclosures for ferals where property owners are willing.”

“If you want to go out and sterilize and release feral cats in your back yard under this scenario, go ahead, but recognize that doesn’t then mean your neighbor can’t then trap and remove them. If you want feral cats to have a good life, adopt them and treat them like real pets. If you aren’t going to, then it is my strong belief the appropriate thing to do is to euthanize them.”

As for how this mass “euthanasia” would play out—you know: budget, time line, population projections, examples of successful models, etc.—Longcore had no more to say than did Schroeder or Hutchins.

Visions of the Future

Is it really so unreasonable to expect TNR opponents—especially those individuals and organizations pushing so hard for policy changes—to present a feasible alternative to TNR? Or even, as a start, to address directly comments made by Mark Kumpf, former president of the National Animal Control Association, who compares the traditional trap-and-kill approach to “bailing the ocean with a thimble”?

“There’s no department that I’m aware of that has enough money in their budget to simply practice the old capture-and-euthanize policy,” explains Kumpf in a 2008 interview with Animal Sheltering magazine. “Nature just keeps having more kittens.” [3]

Those budgets are very likely even tighter today. Now, take away TNR—along with all the “free” resources that come with it—and you’re wishing you had a thimble with which to bail the ocean.

As I explained to Hutchins, those of us advocating and caring for our communities’ stray, abandoned, and feral cats demand better answers than they’ve provided. And it’s becoming increasingly clear that supporters of various organizations opposing TNR are beginning to feel the same way. In part, because—and this, too, is becoming increasingly clear—a position opposed to TNR and the feeding of outdoor cats often, in fact, runs counter to an organization’s stated vision.

Either that, or their “concerns” about outdoor cats are really little more than fear-mongering (a tried-and-true fundraising technique, of course).

The way I see it, there are really only four possible scenarios in play here:

1. No TNR + No Feeding = Fewer Cats

As I’ve pointed out, this one simply doesn’t add up. And heaven knows, if there were evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of such policies, ABC, TWS, the Urban Wildlands Group, et al. wouldn’t be shy about it. That’s not to say they don’t try to suggest as much, of course.

In its TNR “fact sheet” (PDF), TWS, for example, holds up Akron’s 2002 ordinance—which requires the city’s animal control wardens to “apprehend” and “impound” any cats “running at large”—as both humane and cost-effective. Last summer, I took an in-depth look at the impact of Akron’s “cat ordinance,” and found that it’s been far more costly than TWS suggests. And if it’s done anything to reduce the population of the city’s stray, abandoned, and feral cats, nobody’s documented it. (Again, this would seem to be a “success story” in the making for TNR opponents.)

2. No TNR + No Feeding = More Cats—Oops!

What if all this rabid campaigning against outdoor cats has blinded participants to the inevitable consequences of their actions? You know, a careful-what-you-wish-for scenario.

Again, there’s no evidence to suggest that the “plan” will work. And yet, the drumbeat only grows louder. I tend to think that, generally speaking, the leadership at ABC, TWS, the Urban Wildlands Group, et al. is—despite various failures, of which I’ve been highly critical—smart enough to realize this simple fact. On the other hand, I have colleagues—people with far more experience and a much broader perspective—stop me cold when I say so.

3. No TNR + No Feeding = More Cats—But That’s OK

In the 22 months since launching this blog, I’ve been at pains to expose the flimsy nature of most complaints regarding the alleged impacts of free-roaming cats on wildlife and the environment. Much of that effort has involved the untangling of predation estimates based on indefensible sampling and extrapolation, and—more important—decoupling the implied relationship between predation and population-level impacts. Among the evidence I’ve presented (which would seem to be locked tightly inside the aforementioned filing cabinet, thus rendering it “unavailable” to TNR opponents):

Mike Fitzgerald and Dennis Turner’s thorough review of 61 predation studies, in which the authors conclude rather unambiguously: “We consider that we do not have enough information yet to attempt to estimate on average how many birds a cat kills each year. And there are few, if any studies apart from island ones that actually demonstrate that cats have reduced bird populations.” [4]

Also: two very detailed studies supporting a widely understood (though only rarely acknowledged among TNR opponents) pattern of predators: cats tend to prey on the young, the old, the weak and unhealthy. [5, 6] Or, as the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds makes puts it: “It is likely that most of the birds killed by cats would have died anyway from other causes before the next breeding season, so cats are unlikely to have a major impact on populations.” [7]

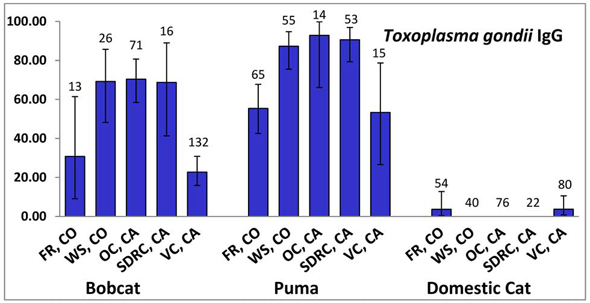

It may be that leaders of the TNR opposition do, in fact, recognize the implications of the well-documented science on the subject (though never publicly, of course), whether that concerns predation, rabies, toxoplasmosis, or any number of other aspects of the debate. Such an understanding would allow them to continue pushing for policies that would, despite their claims to the contrary, actually increase the number of free-roaming cats—but still have little or no significant consequences for the wildlife these organizations claim to protect.

Donors are happy, wildlife’s happy—what’s not to like, right? (Actually, all this unwarranted attention on cats is, I’m sure, diverting scarce resources from the real issues—so maybe the wildlife will, in the end, lose anyway.)

4. No TNR + No Feeding = More Cats. Exactly.

File this one under “A” for Apocalyptic. Or Armageddon, maybe.

What if more cats—lots of them—is not only OK, but the goal? At some point, their numbers become so great that popular opinion undergoes a tidal shift, favoring lethal control methods. The bigger the problem becomes, the more drastic the measures considered.

If some wildlife suffers for the cause, well, it’s a small price to pay. If you want to make an omelet, you have to be willing to break a few eggs, right? No free lunches here. Collateral damage. Etc.

Wild conspiracy-theory talk? Maybe so. I mean, it’s a bit like suggesting that our esteemed Smithsonian Institution hired a cat-killer to conduct research on pet cats. As I often tell my colleagues: you can’t make this stuff up. So.

• • •

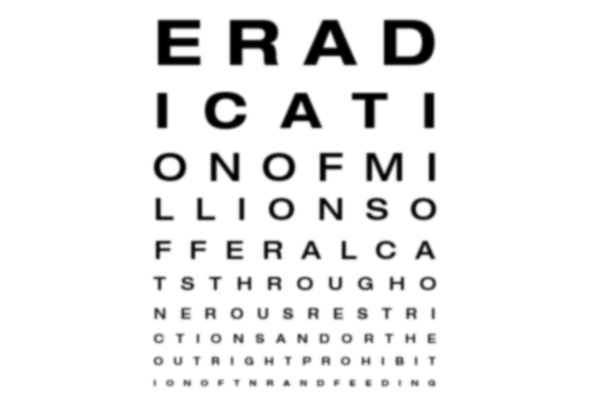

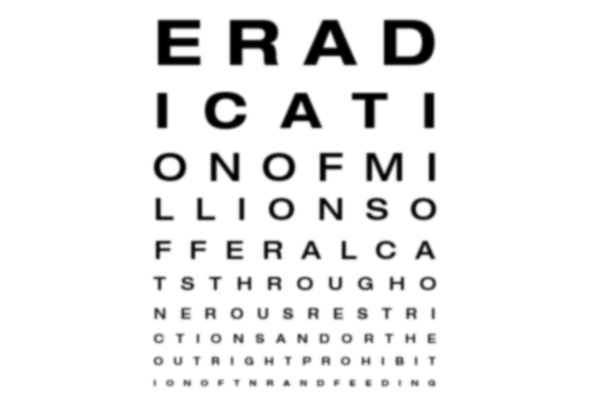

TNR opponents have, for years, misled policymakers and the public—not only about the “threats” posed by free-roaming cats, but about their plan going forward (again, assuming they actually have a plan). They’re advocating for the extermination—in the tens of millions—of this country’s most popular companion animal, without ever proposing any feasible alternative to TNR. (Ironic, isn’t it? These same people claim to have the “best available science” on their side, but either cannot or will not describe or discuss what exactly they’ve got in mind for a solution to the “feral cat problem.”)

Once again, I’m reminded of that famous quote from Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis: “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants, electric light the most efficient policeman.” Public scrutiny and a demand for transparency, Brandeis recognized, can bring about significant social change.

We need to start asking better questions—and demanding better answers—of TNR opponents. And we must do so repeatedly and publicly—in town halls, letters to the editor, and any number of online venues; and by contacting local, state, and federal representatives and government agencies.

No TNR? No feeding of outdoor cats? What’s your plan, then?

As the sunlight Brandies spoke of reveals the fatal flaws underlying the anti-TNR rhetoric, it helps light the way forward.

Literature Cited

1. Bester, M.N., et al., “A review of the successful eradication of feral cats from sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Southern Indian Ocean.” South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 2002. 32(1): p. 65–73.

http://www.ceru.up.ac.za/downloads/A_review_successful_eradication_feralcats.pdf

2. Urban Wildlands Group et al. vs. City of Los Angeles et al. (Case No. BS 115483). Stipulated Order Modifying Injunction. March 10, 2010. Los Angeles Superior Court.

3. Hettinger, J., “Taking a Broader View of Cats in the Community.” Animal Sheltering. 2008. September/October. p. 8–9. http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/taking_a_broader_view_of_cats.html

http://www.animalsheltering.org/resource_library/magazine_articles/sep_oct_2008/broader_view_of_cats.pdf

4. Fitzgerald, B.M. and Turner, D.C., Hunting Behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations, in The Domestic Cat: The biology of its behaviour, D.C. Turner and P.P.G. Bateson, Editors. 2000, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.; New York. p. 151–175.

5. Baker, P.J., et al., “Cats about town: Is predation by free-ranging pet cats Felis catus likely to affect urban bird populations?“ Ibis. 2008. 150: p. 86–99. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bsc/ibi/2008/00000150/A00101s1/art00008

6. Møller, A.P. and Erritzøe, J., “Predation against birds with low immunocompetence.” Oecologia. 2000. 122(4): p. 500–504. http://www.springerlink.com/content/ghnny9mcv016ljd8/

7. n.a. (2011) Are cats causing bird declines? http://www.rspb.org.uk/advice/gardening/unwantedvisitors/cats/birddeclines.aspx Accessed October 26, 2011.